Body Double

| Body Double | |

|---|---|

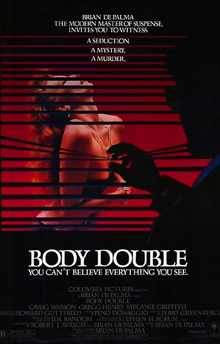

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Brian De Palma |

| Screenplay by | Brian De Palma Robert J. Avrech |

| Story by | Brian De Palma |

| Produced by | Brian De Palma |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Stephen H. Burum |

| Edited by | Gerald B. Greenberg Bill Pankow |

| Music by | Pino Donaggio |

Production company | Delphi II Productions |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million[1] |

| Box office | $8.8 million[2] |

Body Double is a 1984 American satirical neo-noir erotic thriller film directed, co-written, and produced by Brian De Palma. It stars Craig Wasson, Gregg Henry, Melanie Griffith and Deborah Shelton. The film is a direct homage to the 1950s films of Alfred Hitchcock, specifically Rear Window, Vertigo and Dial M for Murder, taking plot lines and themes (such as voyeurism and obsession) from the first two.[3][4]

At the time of its release, the film was a commercial failure, earning just $8.8 million at the box office against a production budget of $10 million, as well as mixed reviews, though Melanie Griffith's performance earned praise and brought her a Golden Globe nomination. Subsequently, it has been better received and is now considered to be a cult film.

Plot

[edit]Struggling actor Jake Scully has recently lost his role as a vampire in a low-budget horror film after his claustrophobia thwarts shooting. Upon returning home to discover his girlfriend cheating on him, Scully splits up with her and is left homeless. At a method acting class, where he meets Sam Bouchard, Scully reveals his fears and the childhood cause of his claustrophobia. They go to a bar where Scully is offered a place to stay; Sam's rich friend has gone on a trip to Europe and needs a house-sitter for his ultra-modern home in the Hollywood Hills.

While touring the house with Scully, Sam is especially enthusiastic about showing him one feature: a telescope, and through it a female neighbor, Gloria Revelle, who erotically dances at a specific time each night. Scully voyeuristically watches Gloria until he sees her being abused by a man she appears to know. The next day, he follows her when she goes shopping. Gloria makes calls to an unknown person whom she promises to meet. Scully also notices a disfigured "Indian", a man he had noticed watching Gloria a few days prior. Scully follows Gloria to a seaside motel where she is apparently stood up by the person she was there to meet. On the beach, the Indian suddenly appears and snatches her purse. Scully chases him into a nearby tunnel, but his claustrophobia overcomes him. Gloria walks him out of it, and they impulsively and passionately kiss before she retreats. That night, Scully again is watching through the telescope when the Indian returns and breaks into Gloria's home. Scully races to save Gloria, but her vicious white German Shepherd attacks him, and the Indian murders Gloria with a huge handheld drill.

Scully alerts the police, who rule the murder a botched robbery. However, Detective Jim McLean becomes suspicious after finding a pair of Gloria's panties in Scully's pocket. Although McLean does not arrest him, he tells Scully that his voyeuristic behavior and failure to alert police sooner helped cause Gloria's death. Later that night, suffering from insomnia and watching a pornographic television channel, Scully sees porn actress Holly Body dancing sensually, exactly as Gloria did. In order to meet Holly, he is hired as a porn actor in Holly’s new film.

Scully learns from Holly that Sam hired her to impersonate Gloria each night, dancing in the window, knowing Scully would be watching and later witness the real Gloria's murder. Offended when he suggests she was involved in a killing, Holly storms out of the house. The Indian picks her up, knocks her unconscious and drives away with her. Scully follows them to a reservoir where the Indian is digging a grave. Scully attacks him, and in the scuffle peels his face off to reveal it as a mask worn by Sam. Scully has been set up as a scapegoat by Sam, who is in fact Gloria's abusive husband Alex, to provide him with an alibi during the murder. Scully is overpowered and thrown into the grave. Though his claustrophobia initially incapacitates him again, he overcomes his fear and climbs out, and Sam is knocked into the aqueduct by the dog and drowned.

During the ending credits, Scully is shown having been recast in his previous vampire role as Holly watches from the sidelines.

Cast

[edit]- Craig Wasson as Jake Scully

- Gregg Henry as Sam Bouchard

- Melanie Griffith as Holly Body

- Deborah Shelton as Gloria Revelle

- Helen Shaver (uncredited) as Gloria's voice

- Guy Boyd as Detective Jim McLean

- Dennis Franz as Rubin

- David Haskell as Will

- Al Israel as Corso, The Director

- Rebecca Stanley as Kimberly

- Douglas Warhit as Video Salesman

- B.J. Jones as Douglas

- Russ Marin as Frank

- Lane Davies as Billy

- Barbara Crampton as Carol

- Larry "Flash" Jenkins as Assistant Director

- Monte Landis as Sid Goldberg

- Mindi Miller as Tina

- Michael Kearns as Mike

- Slavitza Jovan as "Bellini's" Saleslady

- Denise Loveday as "Vampire's Kiss" Actress

- Rob Paulsen as Porno Cameraman

- Brinke Stevens as Girl In Bathroom

- Frankie Goes to Hollywood as Nightclub Band

The film includes appearances from real-life adult performers Linda Shaw, Alexandra Day, Cara Lott, Melissa Scott, Barbara Peckinpaugh and Annette Haven. Steven Bauer, from De Palma's previous film Scarface and Griffith's then-husband, has a cameo as a male porn actor.[5]

Production

[edit]After De Palma's successes of Carrie, Dressed to Kill and his remake of Scarface, Columbia Pictures offered him a three-picture deal with Body Double set to be the first.[6]

Writing

[edit]De Palma created the concept of the film after interviewing Angie Dickinson's body doubles for Dressed to Kill.[7] "I started thinking about the whole idea of the body double," he said. "I wondered what I would do if I wanted to make sure to get somebody's attention, to have them looking at a certain place at a certain time."[8] The erotic thriller was also becoming a popular genre to audiences, with the box offices successes of Dressed to Kill and Body Heat. After fighting with censorship boards over the rating of Scarface — they rated it X and he had to battle to make it R – De Palma resolved to make Body Double as pushback. At the time, he said, "If this one doesn't get an X, nothing I ever do is going to. This is going to be the most erotic and surprising and thrilling movie I know how to make...I'm going to give them everything they hate and more of it than they've ever seen. They think Scarface was violent? They think my other movies were erotic? Wait until they see Body Double."[7][9]

Having been impressed with the horror film Blood Bride, De Palma enlisted its director and writer Robert J. Avrech to write the Body Double script with him. Both were fans of Alfred Hitchcock, and screened Rear Window and Vertigo to gather inspiration. Avrech later described his work on the film as "working off of De Palma's ideas of Hitchcock's ideas."[10]

Casting

[edit]De Palma initially wanted pornographic actress Annette Haven to play Holly, but she was rejected by the studio due to her pornographic filmography.[5] Nonetheless, Haven did appear in a minor role and consulted with DePalma about the adult film industry. De Palma then offered the role to Linda Hamilton, who turned it down in favor of The Terminator.[5] Jamie Lee Curtis, Carrie Fisher, and Tatum O'Neal were considered for the role before Melanie Griffith was cast.[5] De Palma later said Haven "was an enormous amount of help" to him in his understanding of the adult film industry and what Holly's background might be, and Griffith brought "a comic edge that I wanted to be a major part of the tone of the second half of the movie."[8] Griffith was initially reluctant to take the role, thinking she "didn't want any more nymphet roles, but now I think I can bring a lot of life to that kind of character...I think I gave her a great amount of intelligence."[11]

De Palma also considered Dutch erotic actress Sylvia Kristel for the role of Gloria, but she was unavailable. Although he cast Deborah Shelton, he found her voice to be unsuitable and had her lines dubbed by Helen Shaver in post-production.[5]

Body Double contains a film within a film sequence in which pop band Frankie Goes to Hollywood performs their song "Relax"[12] on the set of a pornographic film, and in which scream queen Brinke Stevens,[13] and adult actresses Cara Lott and Annette Haven appear. The club scene was converted into a music video and shown on MTV.[14] Voice actor Rob Paulsen makes a cameo as a cameraman who utters "Where's the cum shot?".[15]

Production

[edit]

Principal photography began in Los Angeles on February 21, 1984.[14] Several locations in and around the area were used, including: Tail o' the Pup, the Beverly Center, Barney's Beanery, the LA Farmer's Market, the Rodeo Collection mall on Rodeo Drive,[16][17] the Spruce Goose dome and Beach Terrace Motel in Long Beach,[18] the Hollywood Tower and adjacent Hollywood Freeway, Tower Records, and the Chemosphere house.[19][20]

Post-production

[edit]The film was initially given an X by the Motion Picture Association of America ratings board. Because many theaters refused to show X-rated films, De Palma had to re-edit the film as he did on Dressed to Kill and Scarface. De Palma cut what he called "a few minor things from the porno movie scene" and secured an R rating.[21] De Palma said Columbia did not support the film due to its excessive violence. He said, "Do you think the guys who run Coca-Cola (Columbia Pictures' parent company) want publicity about violence? They are very aware of their public images, and when they start seeing articles in The New York Times about their product and violence, they go crazy. They're not showmen. They're corporation types."[22]

Themes

[edit]Artifice and illusion

[edit]De Palma said the film deals with themes previously explored in his other films: "visualistic storytelling, a kind of obsessional voyeuristic activity, a sense of humor about the world we live in, manipulators manipulating manipulators."[21] The theme of artifice is demonstrated through Body Double's Hollywood setting—a location itself understood to be in the business of "make-believe"—characters, and plot. The title refers to the filmmaking term for a person who substitutes for another actor in scenes where the face is not shown, but it also acquires a second literal meaning in the film as the audience, along with Jake, is presented with situations intended to deceive.[21][16] The theme is also exhibited in multiple plot lines throughout, such as Jake's belief that it is Gloria he is spying on, Jake disguising himself in order to infiltrate the pornographic film shoot, and the reveal of the killer's identity.[23]

Numerous scenes call attention to their own artificiality and the film's construction, from the opening scene of a desert where the camera then pulls away to reveal the desert is in fact a painted backing on the set of a B-movie.[24][16] Critics noted that with this scene, "De Palma puts us on edge from the start...repeatedly revealing in the first few minutes that what we’re seeing isn't real — it’s all a calculated illusion intended to trick us."[24]

De Palma also makes use of rear projection techniques to emphasize artificialness. Rear projection is used in scenes where Jake drives around Los Angeles following Gloria.[17] The scene of Jake's kiss with Gloria in front of the tunnel uses rear projection and functions as a direct reference to Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo with its 360-degree camera shot.[25][23][24]

The scene on the porn film set soundtracked to Frankie Goes to Hollywood's song "Relax" is referred to by critics as "exhilarating" for its staging and metatextuality.[23][26][27] Filmed in one long unbroken take, the scene segues into a musical sequence without warning and prompts viewers to question whether the action is happening in the porn film itself or the larger world of Body Double.[28]

Manuela Lazic of The Film Stage noted that the scene has "Jake [playing] a parody of his nebbish self accompanied physically and musically by Frankie Goes to Hollywood", and that "the director presents a need to 'fake it 'til you make it' as absolute and inescapable. It is telling of De Palma's joyful cynicism that this scene, an apotheosis of fakery and eroticism, is probably Body Double's most memorable."[23] For the sequence, De Palma allowed his actual camera crew to be visible in shots, further blurring the lines between the film itself and the film Holly Body is making.[16]

Body Double also explores the difference between fantasy and reality as Jake becomes drawn to who he thinks is Gloria dancing in the window. As a voyeur, he attaches a fantasy to her without ever interacting with her in person. When Jake becomes compelled to follow Gloria, she becomes a flesh and blood person to him, more than an object of his fantasies.[23] On a more heightened level, when Jake has his first conversation with Holly after the filming of the porn movie, he is taken aback by her straightforwardness and assertiveness.[16] Holly, "a woman with agency, in full command of her body, career, and sexuality...[appears to be] a rebuke of the illusion Jake held of the leering, lip-licking porn star in Holly Does Hollywood".[16]

De Palma has commented on the deliberate mixing of illusion and reality, saying "It [the film] constantly plays with that. But even though there are great shifts in form, it never really alienates the audience, which is an accomplishment, I feel."[21]

Voyeurism and exhibitionism

[edit]As in his previous films such as Greetings, Hi, Mom!, Dressed to Kill, and Blow Out, De Palma addresses the theme of voyeurism.[29] Critics noted that the act of voyeurism can provide an "illusory, imaginative form of control", a feeling Jake has lost due to his demoted, emasculated position.[23][29] With Body Double, voyeurism becomes tied to exhibitionism, and is used to reflect back on the viewer. Jake, a voyeur who "likes to watch", is understood to be a stand-in for the audience.[25] Voyeurism is turned on its head as it is intimated early on that the woman Jake is peeping on knows her nightly dances are being watched, and with the eventual reveal that the routine is in fact a hired performance.[30]

The scene of Jake first encountering Holly on the set of Holly Does Hollywood is understood to be a commentary on the male gaze.[25] Jake spies Holly in a hallway mirror reflection; as he approaches her, a bathroom mirror captures Jake looking at Holly; thus, the audience is watching Jake watch Holly, who in turn is performing for the porn film and is aware of Jake's presence.

Critic David Denby observed: "Body Double is about Los Angeles, about the eroticized way of life, partly created by the media culture, in which exhibitionist and voyeur are linked by common need. The people live in houses with huge windows; they cruise one another insolently, unafraid of being watched as they watch; privacy is meaningless—there is only the sexiness of endless scrutiny and quick encounter."[31]

Satire of Hollywood

[edit]

Marylynn Uricchio of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote, "De Palma throws in elements of satire and more than nods his head at the whole Hollywood tradition. There's that sweepy, heavy-handed score by Pino Donaggio that punctuates the action with a snide smile. And there’s that 360-degree kiss scene, straight out of Hitchcock, with the highly colored backgrounds of the old Technicolor films."[32] Griffith stated Body Double "is a parody of Hollywood more than anything".[11] Some critics opined that the character of "The Indian", with his garish makeup, is a reference to the old Hollywood practice of using redface to depict Native American characters.[16][25]

Critics have also pointed out that the film's juxtaposition of mainstream Hollywood filmmaking with pornography illustrates that "mainstream films use sex and sexuality in the same manner as exploitation films."[30] By blurring the boundaries between mainstream filmmaking and pornography and showing how illusionism is present in both, Body Double knowingly satirizes the world of Hollywood and its pretenses that it is more "legitimate" than the adult film world.[31]

Release

[edit]The film was previewed for Columbia Pictures executives in Van Nuys ahead of its general release.[14] De Palma says that Columbia was enthusiastic about the film until the screening.[14] Response from the audience was not strong "and the studio started to get really worried," he said. "The only people crazier than the people who criticize me for violence are the people at the studios. I can't stand that sort of cowardice."[22] De Palma and Columbia mutually agreed to end the three-picture deal.[6]

Box office

[edit]Body Double was released to theaters on October 26, 1984, the same day as The Terminator.[33] It opened at number three at the box office, earning $2.8 million in its opening weekend.[34] The film earned $8.2 million over its first three weeks, before being pulled in its fourth week.[1][2] The film earned $8.8 million on a $10 million budget, making it a box office bomb.[1][2]

Reception

[edit]Body Double debuted to a divided response; positive reviews praised the visual style and the performances, while negative reviews criticized the plot, described the Hitchcock homages as derivative, and lambasted the sex and violence as vulgar.[35][36][37] Roger Ebert praised the film, giving it three and a half out of four stars and calling it "an exhilarating exercise in pure filmmaking, a thriller in the Hitchcock tradition in which there's no particular point except that the hero is flawed, weak, and in terrible danger – and we identify with him completely."[38]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote that De Palma "again goes too far, which is the reason to see it. It's sexy and explicitly crude, entertaining and sometimes very funny. It's his most blatant variation to date on a Hitchcock film (Vertigo), but it's also a De Palma original, a movie that might have offended Hitchcock's wryly avuncular public personality, while appealing to his darker, most private fantasies."[39] Writing for The Day, Paul Baumann said, "This is one movie that can make the horrific fascinating and still underline, in a hilarious way, the absurdity of it all."[40] The Schenectady Gazette's Dan DiNicola wrote, "I could not resist [the film's] visual brilliance which without malice or cynicism holds up a mirror to the 'nature' of millions of American viewers."[41]

Griffith received critical acclaim for her performance,[24] with Canby commenting she "gives a perfectly controlled comic performance that successfully neutralizes all questions relating to plausibility. She's not exactly new to films, having played in 'Night Moves,' 'Smile' and 'The Drowning Pool' as a very young actress. What is new is the self-assured screen presence she demonstrates here, and it's one of the delights of 'Body Double.'"[39] Baumann wrote Holly's "wildly incongruous conversations with the earnest Jake get funnier and funnier as the real danger gets closer and closer" and that De Palma can turn "[Griffith's] caustic hectoring of motorists...into a charmed bit of pathos".[40]

Todd McCarthy of Variety stated, "To his credit, DePalma moves his camera as beautifully as any director in the business today and on a purely physical level 'Body Double' often proves quite seductive as the camera tracks, swirls, cranes and zooms towards and around the objects of De Palma's usually sinister contemplation. Unfortunately, most of the film consists of visual riffs on Alfred Hitchcock, particularly 'Vertigo' and 'Rear Window.'"[5][42] David Denby of New York gave a mixed review, but raved about De Palma's "gliding, sensual trancelike style that is the most sheerly pleasurable achievement in contemporary movies."[43] Denby singled out the scene set at the Rodeo Collection mall, writing "virtually wordless, this sustained episode accumulates a kind of suspense that is as much moral and psychological as physical".[43]

Paul Attanasio of The Washington Post positively reviewed the film, writing, "A lewd, gory, twisty-turny murder mystery swirling around Hollywood's porn industry, 'Body Double' finds Brian De Palma at the zenith of his cinematic virtuosity. The movie has been carefully calculated to offend almost everyone—and probably will. But, like Hitchcock, De Palma makes the audience's reaction the real subject; 'Body Double' is about the dark longings deep inside us."[44][45]

Negative reviews opined De Palma was returning to familiar territory by riffing on Hitchcock. In The New Yorker, Pauline Kael shared "the big, showy scenes recall Vertigo and Rear Window so obviously that the movie is like an assault on the people who have put De Palma down for being derivative. This time, he's just about spiting himself and giving them reasons not to like him. And these big scenes have no special point, other than their resemblance to Hitchcock's work."[46] Sheila Benson of the Los Angeles Times panned the film as "elaborately empty" and "silly", suggesting that De Palma "finally may have exhausted the patience of even his most tenacious admirers."[47] Kael added that "the voyeuristic sequences, with Wasson peeping through a telescope, aren’t particularly erotic; De Palma shows more sexual feeling for the swank buildings and real estate."[46]

Some also claimed the plot is ultimately given less importance than the film's visuals.[46][48] TV Guide wrote, "Contrived, shallow, distasteful, and ultimately pointless, Body Double is more an exercise in empty cinematic style than an engrossing thriller. Although cinematographer Burum executes some absolutely breathtaking camera moves, his effort goes for naught when pitted against director De Palma and cowriter Avrech's insipid narrative."[49] Rita Kempley of The Washington Post described the film as a horror comedy, but said it comes off as "sadistic" and does not find a balance "between the comic and the macabre".[36]

The film was criticized for a violent scene involving a woman that some described as an example of sexualized violence.[37][50][51] In the scene, the woman is killed by a power drill; though the drill is never shown entering the victim's body, it is suggestively framed as a phallus.[6][35][52] In a review that awarded two-and-a-half stars out of four, Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune wrote, "When the drill came onto the screen, De Palma lost me and control of his movie. At that point 'Body Double' ceased to be a homage to Hitchcock and instead became a cheap splatter film, and not a very good one at that."[53] In contrast, David Denby noted the film's "violence is so outlandish that only the literal-minded should be able to take it seriously",[43] and argued that its gaudiness appears to address De Palma's detractors "who talk of violence in his films as if it were the real thing", or those who cannot distinguish between the image and actual violence.[54]

The London Clinic for Battered Women asked Columbia Pictures for a percentage of the profits from the film, claiming it was "blood money" for using "the victimization of women as a source of massive profit."[55] In response to the criticism, De Palma said it "was not [his] intention to create a sexual image with the drill, although it could be construed that way."[56][57] He added, "Women in peril work better in the suspense genre. It all goes back to the Perils of Pauline...I don't think morality applies to art. It’s a ludicrous idea. I mean, what is the morality of a still life? I don’t think there’s good or bad fruit in the bowl."[56]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Category | Nominee | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Supporting Actress – Motion Picture | Melanie Griffith | Nominated | [58] |

| National Society of Film Critics Awards | Best Supporting Actress | Won | [59] | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Supporting Actress | 2nd place | [60] | |

| Clio Awards | Award for teaser trailer | Won | [61] | |

| Golden Raspberry Awards | Worst Director | Brian De Palma | Nominated | [62] |

Cult reputation and reassessed response

[edit]In following decades, Body Double underwent a critical reassessment and developed a cult following, with critics citing its directorial and aesthetic indulgences,[16][23] its early 1980s new wave soundtrack, homages to Alfred Hitchcock,[63] and the use of iconic Los Angeles locations.[16][64] Critic Sean Axmaker said that with distance, the film can more easily be seen as a satire of the 1980s era of excess and an image-obsessed culture.[26]

Writing of the 2013 Blu-ray release of the film, Chuck Bowen of Slant Magazine said, "Body Double's consciously derivative thriller plot is as dense with meta-text as any film in De Palma’s career; the searing personal material, which has been buried underneath the film’s superficial happenings with precision and élan, must be discovered with the eyes."[65] Critic Christy Lemire wrote, "What's real, what's imagined and what's movie magic remain mysteries until the end. But the winding road through the hills to get there is always a wind-in-your-hair thrill."[24]

Critics have also commented on how the second half of the film is a subversive commentary on the first part. In an essay for Bright Wall/Dark Room magazine, Travis Woods wrote, "just as the film's reflexive second hour is De Palma’s counter-critique to his critics, it is also a gear-shift into Holly's world, a nightscape L.A. wherein De Palma subverts the tropes he littered throughout the film's first half by employing the postmodern grimy-sticky grit of VHS porn, MTV-styled music video theatrics, and the twisting of a traditional hero's journey dropped into the duplicitous hell of Me-Decade Hollywood."[16]

On the film's finale, Bowen added: "De Palma pulls the entire rug out from underneath the film's reality and turns everything we've just seen into a prolonged Brechtian shaggy-dog joke, only to then pull the rug out from under that joke and halfheartedly reaffirm the film's reality as a mystery-thriller. By the end of this masterpiece, one of the great and most uniquely American films of the 1980s, we only trust surfaces, which are as fleeting and illusory as anything else."[65]

Griffith and Wasson's performances have also been the focus of praise. Lemire wrote, "The scene in [Holly] explains to [Jake] what she will and will not do on camera is a perfect encapsulation of Griffith's charm. She's girlishly angelic but also startlingly no-nonsense. She’s a much smarter cookie than she gets credit for being and her comic timing is slyly perfect."[24] Manuela Lazic of The Film Stage said, "As central character Jake Scully, Wasson turns his conventionally attractive looks into an endlessly fascinating nebbishness and awkwardness. In an early scene, Jake simply walks to his car and jumps in the driver’s seat, yet Wasson manages to turn this casual action into one of the most amusing instances of purposefully bad acting."[23] Griffith later gave credit to the film and the accolades she garnered for her performance for helping to relaunch her film career after a brief absence.[5]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 79% of 39 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 6.2/10. The website's consensus reads: "Exemplifying Brian De Palma's filmmaking bravura and polarizing taste, Body Double is a salacious love letter to moviemaking."[66] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 69 out of 100, based on 18 critics, indicating "generally favorable" reviews.[67]

In a 2016 interview with The Guardian, De Palma reflected on the film's initial critical reception, saying "Body Double was reviled when it came out. Reviled. It really hurt. I got slaughtered by the press right at the height of the women's liberation movement...I thought it was completely unjustified. It was a suspense thriller, and I was always interested in finding new ways to kill people."[68][69] The film helped reintroduce the song "Relax" in America, where it recharted and reached the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 in March 1985.[70]

Additionally, Mark Olsen of the Los Angeles Times named Body Double as one of De Palma's "underrated gems" of the 1980s, stating, "Even more than 'Dressed to Kill' or 'Blow Out,' for me 'Body Double' is the most quintessentially Brian De Palma movie of what might be thought of as his 'high period' — that late-'70s, early-'80s moment when he was making relatively high-budget, high-profile movies that culminated in 'The Untouchables.'"[71] In 2023, IndieWire listed Body Double as number 30 on their list of The 100 Best Movies of the '80s.[28]

Home media

[edit]Body Double was first released to DVD in 1998 with widescreen and pan and scan formats.[12] On October 3, 2006, the film was released as a Special Edition DVD by Sony Pictures .[12] The DVD included the featurettes "The Seduction," "The Setup," "The Mystery," and "The Controversy," all of which cover different aspects of the production and contain interviews with Brian De Palma, Melanie Griffith, Deborah Shelton, and Gregg Henry.[12]

On August 13, 2013, the film was released to Blu-ray by Twilight Time.[65] Special features from the 2006 DVD were ported over. On October 24, 2016, the film was re-released as a Limited Edition Blu-ray from Indicator Series.[72] It included previously released features as well as an interview with Craig Wasson, the documentary Pure Cinema from first assistant director Joe Napolitano, and an illustrated booklet containing an essay by film critic Ashley Clark, a Film Comment interview of De Palma in 1984 by journalist Marcia Pally, and an article from a May 1987 issue of Film Comment in which De Palma gives a personal guide of his favorite films.[72]

In popular culture

[edit]The 1989 black comedy film Vampire's Kiss takes its title from the B-movie Jake Scully acts in.[5][48]

The Bret Easton Ellis novel American Psycho repeatedly refers to Body Double as the favorite film of the serial killer Patrick Bateman because of the power drill scene.[73] Bateman mentions that he has seen the film 37 times and rents the tape of it from a video store several times in the story.[74]

Pop singer Slayyyter cited Body Double as an influence on her 2023 album Starfucker.[75] The cover for her single "Erotic Electronic" is a visual reference to the film's poster.[75]

Remake

[edit]Body Double was remade in 1993 in India as Pehla Nasha.[76] The film was directed by Ashutosh Gowariker in his directorial debut. Deepak Tijori plays the lead role and the movie features Pooja Bhatt, Raveena Tandon and Paresh Rawal.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Body Double (1984)". The Numbers. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Body Double". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Williams, Linda (2005). The Erotic Thriller in Contemporary Cinema. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. p. 86. ISBN 0253218365.

- ^ Cvetkovich, Ann (1991). "Postmodern Vertigo: The Sexual Politics of Allusion in De Palma's Body Double". In Raubicheck, Walter; Srebnick, Walter (eds.). Hitchcock's Rereleased Films: From Rope to Vertigo. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 978-0814323267. Archived from the original on February 11, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Miller, Frank (June 4, 2021). "Body Double (1984)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on May 23, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ a b c Collin, Robbie (September 24, 2016). "Body Double: why Brian De Palma's pornographic fiasco is worth another peek". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Lyman, Rick (February 12, 1984). "Brian De Palma Thinks We Need More Violence In Our Lives". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. 12.

- ^ a b Lyman, Rick (October 28, 1984). "De Palma: A Definition of Suspense". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. I.1.

- ^ F. Knapp, Laurence, ed. (2003). Brian De Palma: Interviews. Conversations with Filmmakers Series. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-1578065165. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Brunwasser, Joan (December 21, 2013). "Behind the Scenes with Hollywood Screenwriter, Robert Avrech". Op Ed News.

- ^ a b Maslin, Janet (June 22, 1984). "A Lot of Life' In 'Body Double'". The New York Times. p. C.10. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Gibron, Bill (September 9, 2006). "Body Double: Special Edition". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on July 28, 2023. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ "Body Double (1984): Acting Credits". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d "Body Double (1985)". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Rob Paulsen: Filmography". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2015. Archived from the original on November 17, 2015. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Woods, Travis (August 3, 2018). "De Palma Does Hollywood". Bright Wall/Dark Room. No. 62. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Isaacs, Bruce (2020). The Art of Pure Cinema: Hitchcock and His Imitators. Oxford University Press. pp. 120–126. ISBN 978-0190889951. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ "Body Double". itsfilmedthere.com. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Timberg, Scott (July 23, 2011). "Landmark House: John Lautner's Chemosphere". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ "Body Double". Film Oblivion. February 25, 2023. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Brian De Palma for Suspense, Terror and Sex, He's the Man for the Job". The Morning Call. October 26, 1984. Archived from the original on August 24, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Blowen, Michael (October 28, 1984). "Bad Boy Brian De Palma Explains Himself". The Boston Globe. p. A8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lazic, Manuela (July 18, 2016). "'Body Double': Brian De Palma's Illusion of Voyeurism". The Film Stage. Archived from the original on May 30, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Lemire, Christy (June 18, 2018). "Christy by Request – Body Double". Christy Lemire. Archived from the original on June 30, 2018. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Dihel, Jake (August 16, 2021). "The Cathode Ray Mission: Body Double and Girls on Film". jacobdihel.medium.com. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Axmaker, Sean (October 21, 2013). "Body Double On Blu-Ray". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Lazic, Manuela; Thrift, Matthew (September 23, 2016). "12 masterful Brian De Palma set-pieces". BFI. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "The 100 Best Movies of the '80s". IndieWire. August 14, 2023. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ a b Bouzereau 1988.

- ^ a b de Corinth, Henri (May 11, 2018). "Watch Closely: Brian de Palma's Surveillance States, 1965–1984". Kinoscope. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Denby 1984, p. 68.

- ^ Uricchio, Marylynn (October 27, 1984). "'Double' dose of too much blood and bodies". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. p. 16. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ "Domestic 1984 Weekend 43". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Scott, Jay (November 1, 1984). "New films in top three". The Globe and Mail. pp. E1.

- ^ a b Darnton, Nina (November 18, 1984). "On Brian De Palma-Crossing the Line Between Art and Pornography?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Kempley, Rita (October 26, 1984). "'Body Double' Is Creepy Crud". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Corliss, Richard (October 29, 1984). "Cinema: Dark Nights for the Libido". Time. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1984). "Body Double". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2019 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b Canby, Vincent (October 26, 1984). "Film: De Palma Evokes 'Vertigo' in 'Body Double'". The New York Times. p. C8. Archived from the original on October 21, 2010.

- ^ a b Baumann, Paul (November 4, 1984). "De Palma still brilliant but...troubled?". The Day. p. B-3. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ DiNicola, Dan (October 27, 1984). "'Body Double' Has Bit of 'Rear Window' Tone". Schenectady Gazette. p. 57. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (October 17, 1984). "Body Double". Variety. p. 15.

- ^ a b c Denby 1984, p. 67.

- ^ Attanasio, Paul (October 26, 1984). "'Double' Boiler". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- ^ Attanasio, Paul (November 4, 1984). "Brian De Palma As Son Of Hitchcock". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c Kael, Pauline (November 12, 1984). "Body Double". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 26, 2023 – via Scraps from the Loft.

- ^ Benson, Sheila (October 26, 1984). "Elevating Voyeurism to New Lows". Los Angeles Times. p. 26.

- ^ a b Newman, Kim. "Body Double Review". Empire. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ "Body Double". TV Guide. Archived from the original on August 24, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Murdoch, Mary Ann (November 2, 1984). "De Palma's 'Body Double' A Cheap Hitchcock Imitation". Ocala Star-Banner. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ DiNicola, David (October 27, 1984). "The Lively Arts". Schenectady Gazette. p. 25. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Bilmes, Joshua (November 7, 1984). "'Body double' is well worth the price". The Michigan Daily. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (October 26, 1984). "Gore overshadows artistry in De Palma's 'Body Double'". Chicago Tribune. p. 7J.

- ^ Denby 1984, p. 69.

- ^ "Women's clinic seeks share of film profits". The Globe and Mail. December 15, 1984. p. M.8.

- ^ a b Plummer, William (December 17, 1984). "Despite His Critics, Director Brian De Palma Says Body Double Is Neither Too Violent nor Too Sexy". People. Archived from the original on July 21, 2017.

- ^ Meenan, Devin (November 19, 2022). "Brian De Palma Chose A Drill For Body Double's Murder Weapon For A Very Practical Reason". /Film. Archived from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ "Winners & Nominees 1985". Golden Globes. Archived from the original on March 26, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (January 3, 1985). "'Stranger Than Paradise' Wins Award". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (December 19, 1984). "New York Film Critics Vote 'Passage to India' Best Film". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Hallam, Scott (July 25, 2012). "Saturday Nightmares: Body Double (1984)". Dread Central. Dread Central Media. Archived from the original on February 10, 2010. Retrieved June 18, 2018.

- ^ "5th Golden Raspberry Awards". razzies.com. Archived from the original on September 11, 2004. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Suton, Koraljka. "'Body Double': Brian De Palma's Uniquely Stylized Erotic Thriller that Pays Homage to Hitchcock". NeoText. Archived from the original on December 14, 2020. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Brian De Palma's 'Body Double': A Hitchcockian Thriller Executed in Completely Original Style". Cinephilia and Beyond. April 11, 2016. Archived from the original on July 28, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b c Bowen, Chuck (August 19, 2013). "Review: Brian De Palma's Body Double on Twilight Time Blu-ray". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Body Double". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ "Body Double". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

- ^ Clark, Ashley (June 7, 2016). "Brian de Palma: 'Film lies all the time...24 times a second'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ Seitz, Matt Zoller (June 9, 2016). "A Movie is a Work of Art: An Interview with Brian De Palma". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on August 24, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ "The Hot 100: Week of March 16, 1985". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ Olsen, Mark; Chang, Justin (June 10, 2016). "Director Brian De Palma's underrated gems, decade by decade". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Atanasov, Svet (October 20, 2016). "Body Double Blu-ray". blu-ray.com. Retrieved August 24, 2016.

- ^ James, Caryn (March 10, 1991). "Now Starring, Killers for the Chiller 90's". The New York Times. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ Green, Steph (November 29, 2020). "The Ingenious Artifice of Brian De Palma's 'Body Double'". The Indiependent. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Varma, Thejas (October 7, 2023). "Pop singer Slayyyter releases second album, 'Starfucker'". The Michigan Daily. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- ^ "Deepak Tijori: I Could Be A Lead Actor But They Never Accepted Me". Outlook. February 26, 2023. Archived from the original on April 14, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bouzereau, Laurent (1988). The De Palma Cut: The Films of America's Most Controversial Director. New York: Dembner Books. pp. 92–96, 113–119. ISBN 978-0942637045.

- Denby, David (November 5, 1984). "The Woman in the Window". New York. pp. 67–69. Retrieved August 26, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Clark, Ashley (May 28, 2018). "Forget it Jake, it's Hollywood: Dreams and Debauchery in Body Double". Archived from the original on June 13, 2019. (from booklet included in 2016 Body Double Blu-ray release)

- Schulze, Joshua (August 12, 2019). "How De Palma Makes Us Feel: The Experience of a Moment in Body Double (1984)". Quarterly Review of Film and Video. 37 (4): 348–362. doi:10.1080/10509208.2019.1646555. S2CID 202536126.

External links

[edit]- 1984 films

- 1984 thriller films

- 1980s American films

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s erotic thriller films

- 1980s mystery thriller films

- 1980s psychological thriller films

- 1980s satirical films

- 1980s slasher films

- American erotic thriller films

- American mystery thriller films

- American neo-noir films

- American psychological thriller films

- American satirical films

- American slasher films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Erotic mystery films

- Erotic slasher films

- Films about actors

- Films about filmmaking

- Films about Hollywood, Los Angeles

- Films about pornography

- Films about stalking

- Films directed by Brian De Palma

- Films scored by Pino Donaggio

- Films set in Los Angeles

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- American self-reflexive films

- English-language erotic thriller films

- English-language mystery thriller films