Eric Easton

Eric Easton (1927–1995) was an English record producer and the first manager of British rock group the Rolling Stones. Originally from Lancashire, he joined the music industry playing the organ in music halls and cinemas. By the 1960s he had moved into management and talent spotting, operating from an office suite in London's Regent Street. Easton met Andrew Loog Oldham in 1963; Oldham wanted to sign an unknown band, called the Rolling Stones, about whom he was enthusiastic. At the time, the band were still playing small clubs and blues bars. Easton saw them once—at the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond—and agreed with Oldham. Their partnership was one of contrasts: Oldham has been described as bringing youth and energy, while Easton brought industry experience, contacts and financing. Together, they signed the group to both a management and publishing deal, which, while giving better terms for the group than the Beatles received, was to the advantage of Easton and Oldham who received a larger cut. Easton was primarily responsible for booking gigs—he was keen for the group to get out of London and play nationally—but also acted as record producer on a number of occasions, including on their first single, a cover version of Chuck Berry's "Come On" in June 1963. Easton was responsible for many aspects of the band's development, ranging from managing their fan club to organising their tour of America in 1964.

As the Stones' fame and popularity increased, so did their expectations of Easton. However, after a number of problems on an American tour, in 1965 Oldham decided to oust Easton from the partnership and bring in New York promotor Allen Klein. Oldham persuaded members of the group to support him and Easton was sacked. The band, with the exception of Bill Wyman, acquiesced. Easton launched a number of lawsuits for breach of contract, and eventually settled out of court for a large sum. In 1980 he and his family emigrated to Naples, Florida, where he went into business; his son, Paul, also became a music manager and booking agent.

Musical context

[edit]During the post-war era, British audiences became accustomed to American popular music. Not only did the two countries share a common language but Britain had, through the stationing of US troops there, been exposed to American culture during the Second World War. Although not enjoying the same economic prosperity as America, Britain experienced similar social developments, including the emergence of distinct youth leisure activities and sub-cultures. This was most evident in the popularity of the Teddy Boys among working-class youths in London from around 1953.[1] British musicians had already been influenced by American styles, particularly in trad jazz, boogie-woogie and the blues.[2] From these influences emerged rock and roll in America, which made its way to Britain through Hollywood films such as Blackboard Jungle and Rock Around the Clock (both 1955).[3] A moral panic was declared in the popular press as young cinema-goers ripped up seats to dance; this helped identify rock and roll with delinquency, and led to it being almost banned by radio stations.[4]

During this period, UK radio was almost exclusively controlled by the BBC, and popular music was only played on the Light Programme. Nevertheless, American rock and roll acts became a major force in the UK chart. Elvis Presley reached number 2 in the UK chart with "Heartbreak Hotel" in 1956 and had nine more singles in the Top 30 that year. His first number 1 was "All Shook Up" in 1957, and there would be more chart-toppers for him and for Buddy Holly and the Crickets and Jerry Lee Lewis in the next two years.[5] The music journalist Stephen Davis notes that, by the end of the decade, "the Teds and their girls filled the old dance band ballrooms" of the kind Easton had played, and Keith Richards called it "a totally new era ... It was like A.D. and B.C., and 1956 was year one".[6] Record production was dominated by five main companies[note 1] and London-orientated until the early 1960s.[8] Similarly, promoters—who often combined the roles of manager and agents for their clients—almost always worked out of London too, and used their contacts in the regional music centres to make bookings.[9]

Early life, career and meeting Oldham

[edit]Easton's[note 2] early life has left very little mark on the record. It is known that he was born in 1927 in Rishton, Lancashire.[11] At some point he entered the music business and is known to have played the organ in cinemas,[12] on piers,[13] and other tourist venues such as the Blackpool Tower.[14] Easton's early work consisted of performing popular pieces such as Ray Martin's "Marching Strings", Richard Rodgers' "Slaughter on Tenth Avenue" and John Walter Bratton's "Teddy Bears' Picnic (which the BBC recorded in Southend for their Light Programme in 1953).[15] He also played with his own ensemble, called Eric Easton and his Organites,[16] and alongside contemporaries on the variety circuit such as Morecambe and Wise, Patrick O'Hagan and Al Read.[17] Easton's career playing around Britain brought him experience of the music business both in and beyond London.[18]

By the time he met Oldham and the Stones he had many years in showbusiness,[18] and, says the music journalist Steven Davis, "an old-line talent agent ... and veteran of variety shows".[6] Musically, the mild-mannered Easton was "a self-confessed 'square'", who kept family photographs on his desk; comments, says the musician and author Alan Clayson, for whom "the depths of depravity" were a 20-a-day smoking habit.[19] Mick Jagger and Brian Jones, who often used a private argot between themselves, would refer to Easton as an "Ernie".[20] Balding and middle-aged by the early 1960s, his company, Eric Easton Ltd, had offices in Radnor House, Regent Street.[12][21] In a later interview, Easton explained how he and Andrew Loog Oldham had met:

I'd only just moved into our offices when a journalist told me about this young publicist, Andrew Oldham. He thought Andy could use a little help, find somewhere to park his feet in London. It seemed he was a very lively young man, so I told him to come round and see me. We had a spare room in the office and I reckoned that it wouldn't do any harm to give this character a helping hand. It worked out fine. I talked over the business with him and we felt we might be in at the start of a useful partnership on the agency and management side.[23][note 3]

Easton later described his business partner Oldham as having "something of the Hayley Mills" about him,[12][note 4] complained about his telephone usage and demanded he itemise his calls.[30][note 5] Oldham—always dapper compared to the strictly suit-and-tie wearing Easton[19]—described their partnership as Machiavellian[32] and as a combination of energy and experience.[33] Wyman agrees that Easton treated them in a business-like fashion when they first met,[29] and Keith Richards later recalled how "if you opened any Melody Maker or NME at the time, you'd see an ad for Eric Easton Management Agency etc.".[34] He described how, as he saw it, Easton[35]

Was now managing a couple of top acts. He's got a business going. He's not a big-time guy, but he's got acts hitting the Top 10. He knows the mechanics of bookings, he knows more than anybody because he's spent thirty years looking for a booking. And in the process, he's found out how it's done and that he's better off booking other people than himself.[35]

Career with The Rolling Stones

[edit]Eric, if sticking out like a sore thumb among the Shakers at the Crawdaddy, hadn't behaved as either a stone-faced pedant or as if visiting another planet. He knew showbusiness forwards as well as backwards, and was perfectly aware ... that the hunt was up for beat groups with sheepdog fringes who, if required, could crank out "Money", "Poison Ivy", "Boys" and the rest of the Merseybeat stand-bys plus a good half of the Chuck Berry songbook.

The Crawdaddy Club

[edit]In 1963, The Rolling Stones comprised bandleader Jones (guitar, harmonica, keyboards), Jagger (lead vocals, harmonica), Richards (guitar, vocals), Wyman (bass guitar), Charlie Watts (drums), and Ian Stewart (piano). Oldham had seen them play the Crawdaddy Club, Richmond[36][note 6] that April[38] and was impressed, thinking they would fill a gap in the British music scene.[12] The Stones were the Crawdaddy's house band, under the aegis of the club's owner Giorgio Gomelsky,[39] who had already "got them eulogized by Record Mirror ... [and] was their manager in every way other than writing".[40] At 19 years old, Oldham was too young to hold a band manager's licence,[41][note 7] and as such he "trawl[ed] the lower reaches of West End theatrical agents" looking for a partner.[44] Eventually, Oldham turned to Easton because he saw the older man as possessing both the financial experience and the contacts in the industry necessary to forward the band's career;[19] Easton also possessed the professional gravitas to give Oldham's involvement credibility.[45] The two discussed the matter.[35] Oldham argued that managing the Stones was "the chance of a lifetime",[35] and begged him to come to the Crawdaddy with him the next week to see for himself.[36] Easton disliked missing[12] Saturday Night at the London Palladium on television, which Oldham called being like going to mass for Easton.[35] Talking to Q Magazine later, he described himself as "an average character of my age, wearing a sports jacket"[46] who hoped his night would not be wasted.[47]

Easton travelled to Richmond with Oldham and, in Crawdaddy's, says Clayson, "stood out like a sore thumb" in the young crowd.[19] Gomelsky was absent, having recently left for Switzerland in order to attend his father's funeral.[39] The future photographer James Phelge, who was also in the audience, later observed that Easton looked like a schoolteacher.[35] For his part, Easton later complained to Peter Jones of his "total humiliation and embarrassment": surrounded by screaming teenagers, in "his heavy tweed suit and his heavy brogue shoes", Easton reckoned he looked a country squire.[48] Of the crowd and the heat, too, he called Crawdaddy's "the first free Turkish bath I'd ever had".[46] Although he "had winced more than once during the performance [he] was experienced in spotting talent", says his biographer Laura Jackson,[49] and recognised it in the Stones. The Stones were willing listeners, and, over a drink after the show[50] it was agreed that Jones would visit the Regent Street office the following week.[51]

Gomelsky knew nothing of events until his return towards the end of the month.[39] A later assistant of Richards, Tony Sanchez, described how, "to Brian and Mick, who wanted–needed–so very badly to make it, walking over a couple of old friends was a small price to pay for the break that Oldham and Easton were offering them".[52][note 8] Gomelsky says that he met with Easton a few days after the Stones had signed to he and Oldham. They wanted, Gomelsky says, to offer him compensation for his previous input to the band's development. What actually concerned them, he argues, was that Gomelsky would allow the group to continue their residency at the Crawdaddy Club.[53] Gomeslky agreed; Easton also began booking them into the Marquee Club and Studio 51, in London's West End, at around the same time.[54]

Signing and Decca contract

[edit]Easton and Oldham were keen to sign the Stones up to a label as soon as possible.[36] Dick Rowe, of Decca Records, had heard of the Stones through George Harrison, but when Rowe tried to contact their agent, no-one appeared to know of one. Eventually, Easton's name was mentioned: "I knew Eric, of course. Once I'd spoken to him, the whole deal went through in a matter of days."[55] Easton and Oldham formed an independent record label, Impact Sounds—through which they would manage the group[36]—and signed them on 6 May 1963 for a three-year deal.[18] Philip Norman describes the meeting:[56]

It was a scene that had already been played in hundreds of other pop-managerial sanctums and would be in thousands more—the walls covered with signed celebrity photos, framed Gold Discs, and posters; the balding, over-genial man at a desk cluttered by pictures of wife and children (and, in this case, electronic organs), telling the two youngsters in front of him that, of course, he couldn't promise anything but, if they followed his guidance, there was every chance of them ending up rich and famous.[56]

Dick Rowe was a friend of Easton's.[33] Rowe—having missed the chance of signing the Beatles the previous year and was still annoyed over it—agreed to sign the band.[36][note 9] For their part, Easton and Oldham retained the rights to the group's recorded material, while the group themselves were effectively leased to Decca.[57][note 10] Easton intended that he and Oldham would cut out the traditional role of the A&R man,[58] to which end they formed Impact Sounds. This would own and hold all master tapes and recordings, which they would also lease—"Spector-like"—when required for distribution.[6][note 11] However, the deal almost did not happen: unbeknownst to Easton and Oldham, Jones had already signed a personal recording contract with IBC. Easton gave Jones £100 with which to buy his way out of his obligations,[6][note 12] and in doing so bought the group's master tapes for themselves.[57][63] The eventual deal with Decca was better news for Easton and Oldham than it was for the band. For example, Easton and Oldman were to be paid 14% of any profits from a single release, but their commitment to the band was for 6%, meaning that Easton and his partner received over half of what was earned.[64]

Easton later told Q that "because there was a lot of interest from other companies, I could go after a really good royalty rate on record sales. And we got it."[47] Sandford comments—reflecting on the group's youth—that "everyone except Easton and Wyman had to have their parents co-sign" their contracts.[65] Easton and Oldham received 25% of the group's earnings in fees.[36] Easton, responsible for the group's wages, personally paid each member £40 a week.[note 13] Wyman says that the band, too, recognised the different qualities Easton and Oldham brought to managing them, calling the two polar opposites.[11] The group collectively saw them as a good combination, believing that Easton, while he understood little of their music was the kind of established agent they needed.[66][note 14] Jagger, in a 1975 The Rolling Stone Interview called Easton "a 50-year-old northern mill owner. It was completely crackers."[67]

Gigs and production work

[edit][Oldham] comes along with this other cat he's in partnership with, Eric Easton, who's much older, used to be an organ player in that dying era of vaudeville after the war in the fifties, when the music hall ground to a halt as a means of popular entertainment. He had one or two people, he wasn't making a lot of bread, but people in real show biz sort of respected him. He had contacts, one chick singer who'd had a couple of Top Twenty records, he wasn't completely out of it, and he knew a lot about the rest of England, which we knew nothing about, he knew every hall.[68]

Easton gained the Stones their early work, among the first of which was a Kellogg's Rice Krispies advert jingle.[69] Easton saw the Stones as a continuation of the homely musicianship shown by the Beatles, Brian Poole and the Tremeloes.[70] Comparing them to the Beatles, he identified a similarity in their beat and upfront guitar playing, "except that the Stones were much more down to earth. More basic."[37] To further emphasise the Stone's resemblance to their Liverpudlian rivals, Easton wanted the group to wear uniform suits on stage, as the Beatles did. They were also to present themselves as all things to all men and women, "direct[ing] Beatle-esque grins" at the audience and avoiding controversy. To this end he attempted to stop band members swearing on stage, to which Jagger muttered "bloody hell". Easton retorted, "bloody hell, you don't say".[19] He considered that compromises had to be made before the British public would accept them: their long hair was an obvious target.[19] For their first photoshoot, Easton bought the band shiny waistcoats, white shirts, slim-jim ties, black trousers and Cuban-heeled boots.[71] Among the band, says rock journalist Paul Trynka, Jones was "the most enthusiastic about the new managers; that spring of 1963 he remained the Stone with whom Oldham and Easton would huddle and share plans".[33] Easton ensured that the group's money was kept in discrete bank accounts, in order to lower their collective tax bill (although in the event, he overlooked that they would also be liable for tax on touring income). Easton also arranged generous credit with fashionable stores in London; this, says Sandford, allowed Jagger and Richards "to run up impressive bills that they waved away airily on presentation".[72]

The first gig Easton booked for the Stones was a benefit concert in Battersea Park organised by the News of the World.[36] Easton had some doubts as to the quality of Jagger's singing voice,[12] comparing it in the negative to Roy Orbison and Elvis Presley.[51][note 15] Sandford describes Easton—"his voice falling to a reverential murmur"—as being worried that the BBC would not approve of it.[12][note 16] As a result, Easton pushed for the band to replace Jagger; Jones seemed agreeable to the suggestion, but Oldham vetoed it,[6] calling them both "completely insane".[75] However, in 1965 Easton told KRLA Beat his reaction to seeing the group play for the first time:[36]

It was absolutely jammed with people. But it was also the most exciting atmosphere I've ever experienced in a club or ballroom. And I saw right away that the Rolling Stones were enjoying every minute of it. They were producing this fantastic sound and it was obvious that it was exactly right for the kids in the audience.[36]

The jazz musician George Melly said Oldham "looked at Mick like Sylvester looks at Tweetie Pie", while Easton was "impressed, but with certain reservations".[11] Easton's son Paul later told how his father was amazed at what he saw in the Crawdaddy, as well as the numbers queuing for entry outside.[50]

Increasing fame, increased pressure

[edit][Easton] was steeped in the showbusiness tradition that the Beatles were beginning to challenge. But if he, and others like him, thought the Beatles were revolutionary, what was he going to make of us on first sight?[76]

In May 1963, Easton supervised the group's first recording session at Decca's West Hampstead studios, where they recorded a cover version of Chuck Berry's "Come On".[6][note 17] Oldham had booked three hours' studio time with Easton's cash, on the proviso, said Easton, that they did not run overtime.[77][note 18] In the meantime, Easton was booking all the gigs he could for the band, and they were playing at least every night, and sometimes twice.[64] The following month the band applied for an audition at the BBC, but were turned down as not suitable.[6] Easton feared that this rejection would prevent the band getting radio exposure.[47] The BBC thought Jagger "sounded too black", says Davis. Once again, Easton argued to sack Jagger, but in the meantime, under pressure from the group's fans, in July the BBC offered Easton a date for the group's audition.[6] The following month Easton began booking the group into a series of ballroom appearances, so marking the end of their days as a club-based blues band, suggests Davis.

Easton deliberately took the group out of London. Their first tour was around East Anglia, playing distant towns such as Wisbech[33]—their opening gig—Soham, Whittlesey and King's Lynn.[79] This was hard work, commented Oldham later, as "most places north of Luton were Beatles territory".[80][note 19] Easton's strategy was to get the band into a habit of non-stop gig; this would make them well known around the country. He was lucky that a nationwide tour by Bo Diddley and the Everly Brothers was about to commence, and Easton was able to have the Stones hired as a backing group. This was relatively successful, suggests Davis, considering the relatively poor showing of "Come On".[79] Although the group saw little immediate change in their circumstances, Easton was organising their future "on the path ordained for an aspiring 'beat' group—the dreary round-Britain path of the pop package show".[82] He was, says Jackson, "busting a gut" to get the group gigs[83] and interviews,[84] and as well as running their fan club from his office.[83] For the remainder of 1963, the group were playing almost every night.[85]

Reviews of the group's first single were, says Norman, lukewarm,[86] but according to Easton, "Come On" sold 40,000 records, and he paid them £18 each in royalties[6] and was incensed when they took the song off their live repertoire soon after.[87][note 20] In mid-1963 they were given the as-yet-unreleased song "I Wanna Be Your Man" by the Beatles. It was to be the Stones' second single and was recorded at Regent Sound Studios on Denmark Street—described by a roadie as "tiny, ropey, and look[ing] like someone's front room"[note 21]—overseen by Easton.[33] The song met with mixed reviews, but Easton's production was praised by Johnny Dean of Beat Monthly.[91] The B-side was "Stoned". Easton, says Davis, "scammed" both the group and his business partner by assigning the rights for the song to a company he had co-ownership in, without their knowledge.[6][note 22] On the other hand, he bought the group a brand new Volkswagen van for their touring needs[6]—"which I thought was very good of him", commented Richards later, "considering he was making a heavy fortune off us"[68]—and regularly acted as producer[93] during their studio sessions, as Oldham often failed to turn up.[94] Easton, says Stewart, did not trust Oldham in a recording studio.[68] He also negotiated free stage equipment from Jennings Music in return for endorsements.[95] On one occasion, the equipment was worth £700.[96]

Easton favoured Brian Jones over the other band members; Davis suggests that a private deal existed between them whereby, for example, when on tour, Jones and his then-girlfriend would stay in nicer hotels, and Jones would receive £5 more in payment than his colleagues for being the frontman.[6] Jones' girlfriend, Lynda Lawrence, later said that "there was this camaraderie, and understanding between them".[33] Easton may have prevented Wyman from being sacked alongside Ian Stewart, whom Oldham wanted to remove as not looking sufficiently part of the band.[12] Easton did, however, acquiesce to Stewart's dismissal;[19] Oldham later came to believe that both Jones and Wyman were a pro-Easton faction within the group.[97]

Problems in America and at home

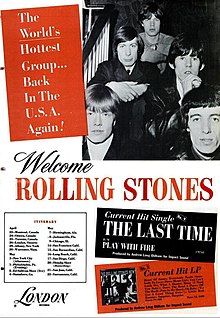

[edit]In June 1964 Easton organised the group's appearance on the BBC's Juke Box Jury. This became extremely controversial, as the group refused to abide by the script, and voted against every record they were played.[note 23] Around the same time, Easton travelled to New York[100] to organise the Stones' first US tour with Decca's subdivision London Records.[note 24] In New York they stayed at the Hotel Astor in Times Square. This was to cause problems: Easton rarely knew either the promotor or the venue he was booking.[101] To save money, everyone shared rooms, and Easton was in the same room as Ian Stewart;[note 25] Norman argues "it was not so much a tour as a series of one-nighters".[101] In an attempt to get the group onto the Ed Sullivan Show, Easton personally visited Sullivan, but Sullivan, Easton later said "threw me out of the place, essentially".[74]

The group also appeared on Dean Martin's Hollywood Palace show; it was not a success. Says Davis, Martin "went out of his way to insult them in his introduction". As a result, Jagger phoned Easton—by now returned to the UK[103]—"and yelled at him".[6] For Easton, says Stewart, the Hollywood show "was the thin end of the wedge".[68] Easton was blamed for a poorly-organised circuit: while some shows in New York were well attended, on other occasions they played to small crowds, either in massive stadia such as the 15,000-seater Detroit Olympia[64]—where they played to an audience of about 600 people[104]—or fairgrounds and fields in Nebraska[64][68] (where, Wyman later recalled, "you could just tell they wanted to beat the shit out of you").[103][note 26]

There was growing tension between Easton and Oldham as well, as the latter had "discovered that Easton had demanded kickbacks from local promoters" while they were touring.[6] Easton, meanwhile, found Oldham's erratic behaviour bizarre. In his attempts at creating an image for himself, Ian Stewart describes Oldham as being "more interested in the image of Phil Spector, running around in big cars, with bodyguards, collecting money, and buying clothes" than producing records.[105][note 27] Easton, says the author Fred Goodman, "as unflinchingly middle class as any man who ever worked in the music business, could only scratch his head". The group's road manager, Mike Dorsey, visited Easton in Ealing and asked him to control Oldham.[105][note 28]

Easton—who by this time saw the group as being as big as The Kinks[107]—had booked the group to top the bill at the National Jazz and Blues Festival in Reading, with 50% of the door receipts for the band, who were to be billed as "the triumphant return for the conquering heroes" of America.[108] Soon after they appeared on the BBC's flagship music programme, Ready Steady Go!. When they left, Jones was left behind because of the fan crush; Easton gave him a lift, with Jones hiding in the floor of the car.[109] The autumn of 1964 British tour saw Eric Easton Ltd receive 20% of the tour profits, and when the Stones beat the Beatles in the Melody Maker's popularity poll, Easton brought each member a new watch.[110] Following the tour, however, Easton and the group sued the tour promoter, Robert Stigwood for supposedly withholding profits. Easton wrote to Stigwood, "we have made every effort to settle the matter amicably, unfortunately without success. The Stones were paid their basic salaries as agreed. This action is over profits".[111]

On the group's second US tour, in late 1964, Easton caught pneumonia in New York and returned to London to recover. Following his illness, he contemplated a world tour, with the taking in Australia, New Zealand and the Far East.[112] At about this time, Easton found out that Watts had secretly got married the previous month, and commented: "I suppose now I will have to buy him a wedding present". Meanwhile, relations continued to sour with Oldham. While the group was in America, Easton booked them onto several radio shows in the UK, including Saturday Club and Top Gear. Oldham found out and cancelled; when the group failed to appear for the BBC shows, the fans were angry and the BBC engaged its lawyers.[113] Easton was under pressure to make deals for the band that were as good as the Beatles had had; he wrote to his US concert agent, Norman Weiss, saying:[114]

I always have to reckon with the fact that the boys have a permanent picture in mind of the Beatles' $1 million-dollar, ten-day stint. Their idea is: if Eppy [Brian Epstein] can get this sort of deal for the Beatles, why can't you get it for the Stones? While I realize that miracles take a little longer to perform, I have at least got to kid myself that I am making the effort to actually perform miracles.[114]

Discontent within the group

[edit]We wanted to do something the Beatles hadn't done first, so I thought maybe an appearance at London's West End. It's London's answer to Broadway ... Brian Epstein and I were sort of rivals, you see. But my friend told Brian he could have the Prince of Wales on Sundays. I was furious, so I went out and put a show on at the Palladium with the Stones. The Stones only did one show at the Palladium, but that's where we beat the Beatles. I was always looking for a way to beat the Beatles, and especially Brian Epstein. At least we beat the Beatles at one thing.[74]

As the group became more famous, says Forget, the pressure on Easton was beginning to show. Oldham had been predominant in dealing with the Stones' image and creative development. Easton attended to the financial side, but the group was concerned, says Forget, that Easton would be unable to manage the band's approaching fame.[18] Richards believes that Easton—who he said was tired by then—may have been ill, and this may have affected his work.[115] Either way, he said, he felt that Easton "wasn't big enough to handle anything outside of England".[68] He expanded on this in a 1975 Rolling Stone Interview, saying that once the band broke America, "this cat Easton dissolved. He went into a puddle. He couldn't handle that scene."[116] Wyman, on the other hand, contests Richards' view of Easton's departure, saying that it was "untrue and a camouflage. Easton functioned efficiently."[117] Easton had also helped sour relations with Oldham: claiming that their work for the Stones was now so big that it necessitated more office space, Easton evicted Oldham from his backroom in Regent Street. Oldham suggests that "in fact, Eric was just totally pissed off. He'd had it with me, my style of personal management."[118]

Although Easton had organised another Stateside tour for autumn 1965,[119] the band was increasingly unhappy under his management. Although they had earned millions touring, they only received £50 a week from Impact Sounds and, says Davis, were permanently short of money.[6] Oldham—by now having moved out of the Regent Street office and no longer on speaking terms with Easton[97]—"wasted no opportunity to bad-mouth his partner to Jagger and Richards",[64] emphasising Easton's lack of "hip" or "cool".[120] Communication between the two had been difficult for some time, says Wyman,[121] who also notes that, although a number of contractual discussions were taking place between Oldham and the group, Easton "was conspicuously absent" from them.[122] Oldham also sent Easton telegrams in Jagger's name, which Easton only discovered were not from the singer when the two spoke on the phone and Jagger denied all knowledge of them.[123] Easton for his part reminded Oldham that, as far as he was concerned:[124]

You and I, as the joint managers of the Stones, have a joint responsibility to advise our Artists as to their contractual obligations. It seems to me to be quite clear that one thing we must do is to advise them to fill their contracts and I feel sure that on reflection you will agree with me on this.[124]

By July 1965[6]—partly motivated by Oldham's exposure of Easton's underhand dealings with Jones[125]—Oldham and the Stones had agreed that Easton would be forced out.[6] Trynka argues that it was Jones' extra £5 that acted as a catalyst for the others' discontent: "The extra fiver marginalized Easton and Brian—and Oldham used it to his advantage".[33] Wyman seems to have attempted to mount a defence of Easton, but, according to Goodman, he was shouted down by Richards, who accused the bassist of being "fucking mercenary".[126]

On 27 August 1965 at a "bitterly acrimonious" band meeting, a number of allegations were made against Easton, who Wyman says kept his cool throughout the proceedings.[127][128] Easton reminded the group—and Oldham and Klein—that as far as he was concerned, his contract still had nine months to run;[129] he also argued that Oldham had withheld payments from him.[130] Easton was replaced by New Jersey-born record company auditor Allen Klein,[18][note 29] who Norman says "dazzled" Oldham.[131] For his part, Oldham may have been worried about the immediate future: the Stones' contract with Decca was about to expire, and he may have feared that if Easton had the opportunity to renegotiate it, he might exclude Oldham.[132][note 30]

Dismissal

[edit]

Easton was also sacked as the group's booking agent and replaced by Tito Burns.[6] Clayson suggests that Easton's dismissal was as a result of divide and conquer tactics by Klein, who had originally been employed to undertake some of Oldham's administrative work but was able to persuade Oldham that Easton was no longer required.[133][note 31] Trynka says Easton was sacked in favour of the "far more predatory Allen Klein" by an Oldham-Jagger-Richards triumvirate.[33] In 1968, Easton's barrister described him as having been ousted,[136] and music writer Nicholas Schaffner later called it a purge on Oldham's part.[137] It is likely that Richards was the prime motivator behind the move;[138] one of the things he liked about Klein was that "at least he was under fifty".[139] Easton was summarily sacked,[33] and an attempt to buy him off failed.[133] In October 1971,[128] Easton launched a series of lawsuits for breach of contract[140] against the band, Oldham, Decca, London Records, Allen Klein and Nanker Phelge.[128] As a result, the High Court froze a million pounds-worth of the Stones' UK assets until the case was concluded. Decca was also instructed to suspend all royalty payments to the group.[141] This process was to last many years. Wyman was, in his own words, "the lone voice to express reservations".[33][note 32]

Easton's barrister, Peter Pain, told the court that "in many ways, the whole story is rather sad ... it is probably no exaggeration to say that everybody is suing everybody".[136] Easton attempted to enforce a prison committal against Oldham for failing to pay monies owed or to supply documentation.[142] Oldham, says Goodman, was keen to avoid Easton's lawsuit if possible and was[143]

Very nervous. In the three years since his split with Easton, he'd gone to extraordinary lengths to avoid his former partner (and to avoid being served with legal documents), including using a body double and climbing out of an office window.[143]

While Oldham's paranoia and fear of a trial for perjury increased, Easton appears to have found the affair little more than "disheartening or silly";[143] the first time Oldham ran away from him, Easton called after him "you'll have to accept them [the documents] sooner or later, you naughty boy ...".[144] It was two years before Oldham was eventually brought to earth,[145] and Easton's lawyers confronted Klein robustly in November 1967.[note 33] Easton eventually settled for a golden handshake[68] of $200,000 in withheld royalties, in exchange for which he would drop his future claims.[140] On the other hand, according to Easton himself, he voluntarily left the band, on account of the lifestyle not suiting him and the "unsavoury people" he was forced to deal with.[146]

Later life

[edit]Easton attempted to put his own side of the story across, but according to Trynka, he was frozen out of the popular music press who "only talked to winners, not losers". According to the Melody Maker writer Chris Welch, who interviewed Easton, he was "sad and despondent"; Welch's interview was, however, spiked by his editor Ray Coleman, whom Welch believed to have been influenced by Oldham.[33] Easton sued Oldham for breaking their contractual partnership, although, suggests Jackson, "he had difficulty serving the papers on Andrew as he would literally leg it".[147] The group's subsequent contracts with Decca and London Records—arranged by Klein—explicitly excluded Easton from claiming anything from them in future.[148] Richards summed up the perspective of the group on Easton's departure:[68]

He'd served his purpose—we'd done as much as we could in England. We could get a grand a night, and that's as much as you could earn, in those days. You think, what the fuck do we need him for ... because that was the way it was. Onward.[68]

The group's 1966 single, "Paint it Black"—later the opening track on the album Aftermath, had its origins in what author Tim Dowley calls a "mickey-taking session"—a send-up, says Richards[149]—out of Easton, in which Wyman played a Hammond organ.[13] Richards later recalled how, "Bill was playing the organ, doing a piss-take on our old manager [Easton], who started as an organist in a cinema pit. We'd been doing it with funky rhythms and it hadn't worked out and he started playing it like this [a sort of unintentional klezmer parody]".[6][149] It was also, suggests Trynka, "in tribute to [Easton's] earlier career as an organist on the chicken-in-a-basket circuit".[33]

Jones had been "profoundly disturbed" at the expulsion of Easton, "his one ally" in the group by then, and Easton's departure contributed to Jones' descent into depression and drug use.[150] Easton was still in business in 1967 when he had moved his offices to Little Argyll Street, around half a mile (0.80 km) north along Regent Street.[151] Following the death of Jones in July 1969, Easton attended his funeral in Cheltenham along with Wyman and Watts .[note 34]

Easton attended a birthday party that was held jointly for Richards and Bobby Keys at Olympic Studios on 18 December 1970. In 1971, the Stones—facing a serious financial crisis[6]—sued Easton and Oldham, among others, for failing to ask Decca Records to increase their royalty payments, which, alleged Jagger, it had turned out Decca had been willing to do but had not been asked to.[23][note 35]

Other work

[edit]Easton managed a number of other bands and artists, particularly of the middle of the road genre.[19][154] Among his clients he counted David Bowie's first group, The Konrads,[155] although the Konrads, unlike the Stones, "never progressed beyond the suburban pub circuit", says Sandford, and may not have been particularly interested in them. [156] Easton also ran Julie Grant[157]—whom Easton saw as a successor to Helen Shapiro[158]—and booked her to back the Stones on their first UK tour.[159] Easton claimed to have managed the Dave Clark Five before the Stones,[73] and organised their first American tour. His partnership with them, though, says Easton, ended because the group thought him to be concentrating too much on the Stones and not enough on them.[160][74] Easton also managed Bert Weedon,[157] Mrs Mills[19] and the host of ITV's popular music show Thank Your Lucky Stars, Brian Matthew. Through Matthew, Easton had arranged the Stones' first TV appearance.[6] Clayson says that Easton was "respected and liked by his many prestigious artistes" due to his background in the industry and the fact that he was committed to their long-term success. For example, for Weedon he had obtained a residency on the BBC's Billy Cotton Band Show, and Mills he obtained a place for on ITV's children's series, the Five O'Clock Club.[19] According to Peter Townsend, Easton believed that the Stones' impact would be ephemeral and that it would be his other clients—Grant, Weedon and Mills—who would be his long-term investments. Easton, says Townsend, also had other sidelines to buffer him financially, telling Townsend, "if this popular music business collapses, I'm not terribly worried. I've got a nice little income guaranteed; I hire out 20 organs to Butlins."[80]

Personal life

[edit]For much of his career, Easton lived in Ealing.[161] He was married—his wife had been a dancer[14]—with two children, and "his one luxury was a caravan on the south coast", wrote Oldham later.[161] In 1980, Easton and his wife were holidaying regularly in Florida. First, they stayed in Miami and then made their way down the Tamiami Trail to Naples, to where they decide to retire the same year.[146] There he opened Easton's Music Centre[73]—trading in pianos and organs—and a real estate business.[74] In an interview, Easton later claimed to have kept in touch with the Stones into the 1990s.[160]

Easton was married to Mary,[146] with whom he had a son, Paul. Paul also went into the entertainment industry,[160] forming ABA Entertainments Consultants.[162] Easton and Paul took in concerts together when artists were in the area,[162][note 36] and Paul himself, said Easton, undertook a "whirlwind tour" of the UK in 1990 at the Stones' invitation. The invitation, said Easton, was the result of the group vacationing in Naples, and the Eastons dining with them.[160][note 37] Paul later said that his father's business ensured he grew up what he termed a "showbiz brat".[164]

Easton died in 1995, 67 years old.[165] In his 1998 autobiography, Oldham writes that sometime in the "early 90s", after hearing that Easton had not long to live, he telephoned him in Florida "to attempt a closure to all our acts on this earth. Eric came to the phone, but didn't really want to speak with me—his call."[166] Following his death, the Eric Easton Awards were launched in Naples; named after him, they were intended to highlight the three best local student pianists of the year with a public recital.[167]

Reputation

[edit]Trynka calls Easton "the forgotten man of the Stones story".[33] Clayson argues that, notwithstanding Easton's own prim dislike of the beatnik culture, it did not "prevent him from turning a hard-nosed penny or two when the opportunity knocked".[19][note 38] Wyman, speaking to the Evening Herald's Eamon Carr in 1990, also believed that, while the Stones in their early days were consistently poor—"all the expenses went onto the band", he said—Oldham and Easton, "probably were quite wealthy". This, suggests Wyman, was both on account of the management team earning twice what the group did, and also that, following their departures, both men received large pay-offs.[169] Giorgio Gomelsky—whose interest in the Stones was "cultural rather than business-orientated"—was unimpressed by either Easton or Oldham, saying "frankly, I thought those two were pretty low-flying characters with no interest in blues, underdog culture or social justice! Dollar signs were pointing their way."[53][170] The publicist and talent scout Lesley Conn also thought that Easton was a bad choice of manager for the Stones, arguing that Easton "really screwed 'em to the wall".[80] Richards, likewise, considers that Easton and Oldham "fucked Giorgio",[171] although Oldham says that neither he nor Easton knew of Gomelski's existence when they signed the band.[172]

An artist is what he or she Is born. A manager or producer shouldn't kid himself and think he's made them. You can't mould an artist ... I sum It up with the word "charisma". The difference between two good artists is that the star has charisma. And who can teach charisma?[74]

To the contemporary music journalist Sean O'Mahoney, Easton was "vital. Andrew knew nothing about the business side of it ... he needed someone who did."[118] Easton was conservative, businesslike and practical[173] as well as "calm, dependable and knew the ropes". he was generally "much-maligned", argues Trynka.[33] Decca executive Dick Rowe called Easton "respected, a steady pair of hands he could rely on".[33] Easton was also highly trusted by journalists.[33] Oldham later criticised Easton as lacking artistic vision, while the music executive Harold Pendleton says of the two men's relationship that "Eric Easton was a run-of-the-mill manager, calm, cold and efficient. Loog Oldham was a temperamental chancer and a fellow who understood artistic people. The combination of the two was better than either of them apart."[33] Within the band, Easton was most respected by Wyman, who was a few years older than his colleagues and did not see Easton as distant from the group as they did.[94] Clayson suggests that age was the relevant factor, as the few years Wyman had over the other Stones meant that he had a similar experience of the post-war depression as Easton.[168] Wyman later described Easton as a "cautious, kindly" figure, diligent in his work and treatment of his clients.[11] Richards called him a "very nice guy".[174] The band generally respected Easton, says Norman, for financing them when they were an unknown quantity, "and whom, in spite of his desperate naffness, they all rather liked".[175] He also emphasised the dangers, in his opinion, of letting hindsight colour the importance of Easton in the group's progression:[176]

It's easy twenty-five years later to put a guy like Eric Easton down as a boring old-time agent who didn't understand what young tigers like the Stones were driving at, but he worked hard and well for us. He put his faith in us and was there when we needed support, and he had an office machine that ticked smoothly. It's crucial to any band to have good organization; it's no good having a brash ideas-man like Andrew Oldham if there's no support system. We were well served in those early days.[176][note 39]

In 1991, Easton told a reporter that he was glad the Rolling Stones had become as successful as they had, as "it sort of shows that I know what I'm doing, too, doesn't it?"[178]

Discography

[edit]Brian Jones, accompanied by Mick Jagger, came up to Eric's office as arranged at two o'clock the next Tuesday. We sat down and played mixed doubles. Eric Easton, former pier organist from up north, now a nigh-on-fortyish, unassuming, slightly greying, bespectacled, open-faced man, sat behind his desk with a twinkle in his eye. Eric had that twinkle from the time I meet him, on most occasions, till sometime in 65. He got the money, I hope he got a life and got the twinkle back.[166]

| Format | A-side | B-side | Producer(s) | Studio | Release date | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Unreleased) | Love Potion No. 9 | N/A | Andrew Oldham/Eric Easton | Olympic Studios | May 1963 | [179] |

| Single | I Wanna Be Your Man | Stoned | Eric Easton[note 40] | Kingsway Studios | 1 November 1963 | [181] |

| N/A | Fortune Teller | Poison Ivy | Eric Easton/Andrew Oldham | Decca Studios | January 1964 | [180][182][note 41] |

| EP | The Rolling Stones | N/A | Eric Easton | Decca Studios/De Lane Lea Studios | 17 January 1964 | [181] |

| Single | Not Fade Away | I Wanna Be Your Man | Andrew Oldham (A-side); Eric Easton (B-side) | Kingsway Studios/Regent Sound | March 1964 | [183] |

| Album | The Rolling Stones | N/A | Eric Easton | Regent Sound | 26 April 1964 | [183][128][note 42] |

| Single | Tell Me | I Just Want to Make Love to You | Andrew Oldham/Eric Easton | Regent Sound | June 1964 | [183] |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Decca Records, EMI, Columbia, HMV and Parlophone; the first independent label, Top Rank Records, emerged in 1959.[7]

- ^ The Stones' historians Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon have noted that "the name Easton had historical connections with the phonographic industry through Edward D. Easton, one of the founders of Columbia Records, which was established in association with a group of investors in Washington, DC, in 1887".[10]

- ^ Oldham later described their meeting in his autobiography: "Eric was grey-haired, grey-suited, and in his mid-thirties—to someone my age that put him over the hill, but for workspace at only £4 a week I decided to like him and his fifth-floor Regent Street office".[24] Oldham rented a desk[25] and also dwelt in a backroom;[14][26] Easton paid him £7 weekly.[27] The Rolling Stones' photographer, Philip Townsend, described how in Easton's office suite:

You walked into a reception area. Eric's office was on the right-hand side. If you went through an arch on the left, there was an office about ten by six [feet], that was Andrew's."[14] Also on Easton's staff was his father-in-law, Mr Boreham, who advised Easton's clients on long-term financial planning.[28]

- ^ Jones gives a flavour of Oldham's career up until then:

Whatever craze, whatever phase there was, he would come round to the Record Mirror offices and he would be in on it. For a while, he wanted to make a name for himself as a comedian, and for a time he was called 'Sandy Beach,' which we said was totally improbable. Then he wanted to call h1mself 'Chancery Lane', and we listened through these things and said, 'Yes, Andrew ... okay, Andrew ...'"[29]

- ^ Bent Rej later recalled Easton being also concerned at Brian Jones' telephone usage. Jones would regularly spend hours making transatlantic calls to Bob Dylan, at a time when the telephone was still relatively uncommon in the UK.[31]

- ^ Oldham had been informed about the group by Peter Jones, a friend of his working at the News of the World; word had spread about the Stones' sound, and regular attendees at the Crawdaddy included David Bailey, Jean Shrimpton, Eric Clapton and the Beatles.[37]

- ^ Oldham later explained

Oldham had previously offered the joint-management of the Stones to Brian Epstein, who turned the offer down as the Beatles were a full-time occupation.[42] Oldham later recalled that he felt it ethically improper not to offer his ex-employer his new discovery, "but I hoped he was not listening; he was not, so I made my bed with agent Eric Easton and the Stones jumped in with me".[43]I wanted to manage [the Stones], but GLC regulations at the time meant that you could not function as a manager without an agent. You could manage, but you couldn't book gigs without the licence. I needed Eric because he had the licence.[6]

- ^ After losing the Stones to Oldham and Easton, Gomelsky went on to manage The Yardbirds;[41] he later remarked of the Stones:[47]

I thought we had a verbal understanding and felt tremendously let down when they left me. But I never like to work with monsters, no matter how talented. They had this satanic power. Jagger was organised and ambitious, but selfish. Keith was very spoilt. Jones should have had treatment. His responses were never those of a normal person".[47]

- ^ Indeed, Rowe had also previously rejected the Stones' demo tape when they had sent it in months earlier,[44] and the music author Philip Norman has described Rowe as "the most unenvied man in British pop music".[55]

- ^ Decca was hapless, comments Davis,[6] and, says Nigel Goodall, was a better deal than the Beatles had.[57]

- ^ Wyman later acknowledged that the band were inexperienced in the industry's business matters, but says "to be fair to Oldham and Easton, owning our own tapes rather than signing ourselves away to a giant company (like the Beatles and hundreds of others had done) was in 1963 a very shrewd move".[59]

- ^ IBC sound man as that had been the price of their studio time with IBC.[60] Glyn Johns later suggested that—IBC manager George Clouston never having met the Stones in person—Jones looked "like nothing he had ever witnessed, with [his] odd clothes, attitude, and long hair. [Coulston] probably couldn't wait to get them out of his office."[61] Johns was a good friend of Ian Stewart's and had been instrumental in IBC receiving the Stones' demo tape.[62]

- ^ This was the equivalent, notes Sandford, to what Jagger's father—a teacher—brought home in a month.[12]

- ^ Ian Stewart, for example, suggests that, in his view, Easton "didn't know anything about pop music",[47] and Bill Wyman later wrote that Easton was "the least likely person ever to have stepped foot in a rock 'n' roll club".[11]

- ^ In 1991, Easton told a reporter that, conversely, "there are hundreds of better singers, but there will never be another Mick".[73]

- ^ According to Easton, speaking in 1984, the suggestion to get rid of Jagger on account of his voice was not his, but the BBC music manager who had turned down the Stones' audition: "That's always attributed to me in books", says Easton, "but it's not true. Of course, we can all laugh about it now."[74]

- ^ Berry had released the song two years earlier in the United States, but it remained unreleased in the UK until now.[6]

- ^ They finished before time, notes Norman, "so sparing Eric Easton a five-pound surcharge".[78]

- ^ Oldham attended the opening gig in Wisbech, and complained about "what passed for toast the next morning in the B&B"; after that, he says, he returned to London and "left it to the band to clobber the aliens anyway they could".[81]

- ^ The group only performed it live eight times, and would not do so again until the 50th anniversary of its release, when they played it on 6 June 2013, on their 50 & Counting tour.[88]

- ^ To aid acoustics, Regent Sound Studios had egg boxes stuck to the ceiling.[89][90]

- ^ This was Southern Music, within which Easton controlled the Southeastern Music division. The group never regained control over the song.[92]

- ^ The series, hosted by David Jacobs, featured celebrity showbusiness guests on a rotating weekly panel who were asked to judge the hit potential of recent record releases as either hits or misses. It was the only time more than four jurors attended.[98] Richards later said of their behaviour, "we just trashed every record they played".[99]

- ^ London Records' "best-selling act was Mantovani, king of mood music", comments Davis, "and the label was clueless when it came to marketing the hot English acts it now got from Decca".[6]

- ^ Jones was in with Wyman, Jagger with Richards and Watts with Oldham.[102]

- ^ In San Antonio, Texas they played a teen fair standing on the edge of a water tank full of trained seals.[101] At another point on the tour, a member of Easton's staff beat up Brian Jones for hitting a girl who had spent the night with him.[78]

- ^ Ian McLagan, the Small Faces keyboardist had had experience of Oldham's production style, commenting that in his view, Oldham was "an idiot. He has no idea about sound. He couldn't produce a burp after a glass of beer."[106]

- ^ Paul Easton later told Goodman that "I think Andrew frustrated my dad ... he would disappear; he wouldn't do the little things that needed to be done".[105]

- ^ Klein, says Forget, had established a reputation for being able to force big record companies to pay their artists many thousands of dollars in accrued rights.[18] According to Jagger later, "Andrew sold him to us as a gangster figure, someone outside the establishment. We found that rather attractive".[6]

- ^ Oldham's position had been insecure since an incident in Chicago, during the first US tour, when, high on alcohol and amphetamines, he had produced a gun in Richards' hotel room and had to be physically restrained.[132]

- ^ Oldham's career with the Stones outlasted that of Easton by two years. Oldham's relations with the group were increasingly strained by his drug use and consequent inattention to the group's requirements. When Jagger and Richards were arrested for drug possession in January 1967, instead of devising a strategy for their legal defence and public relations, Oldham fled to the United States, leaving Klein to deal with the problem.[134] Oldham was forced to resign as manager of the Rolling Stones in late 1967 and sold his rights to the group's music to Allen Klein the following year.[135]

- ^ The club promotor Jeff Dexter, who had worked with Oldham, commented on Oldham's treatment of Easton,

Given what Andrew actually had at that time, it just shows how lacking in self-belief he really was. He'd always had that fantasy of trying to be someone else—and he looked up to the dodgiest American. To allow a cunt like that to come in and take it all ... it's unforgivable. [33]

- ^ Indeed, Goodman speculates that they may have attempted to tap into a vein of antisemitism on account of Klein's ethnicity, whom they portrayed as a predator.[140]

- ^ It was not possible for Jagger to attend, wrote Wyman later, as he was in Australia, but Wyman said he was saddened at the absence of others, including Keith, Oldham and Klein.[152]

- ^ Allan Klein was also being sued.[6] Bryan Jones had by now died, and his father, Lewis-Hopkins Jones cooperated with the Stones on behalf of Brian's estate.[153]

- ^ On one occasion, discussing a recent Barry Manilow show they had attended, he highlighted the difficulty in selling seats for big tours. A third of the seats at the Manilow show were empty, he said—while emphasising that he had nothing to do with the promotion himself—said Naples was a "difficult and unpredictable" area for music promotion>[162]

- ^ In November 1989 The Press-News reported that the Stones would be recuperating in the Naples Ritz-Carlton between the Miami and Tampa gigs of their Steel Wheels/Urban Jungle Tour.[163]

- ^ Indeed, Clayson compares Easton to "a stereotypical pop group manager from a monochrome Ealing film such as 1959's Idol on Parade "... as if all he liked about his pop charges was the money they could generate, selling them like tins of beans – with no money back if they tasted funny".[19] Clayson does, however, also call Easton "the more venerable" of the Stones' managers.[168]

- ^ Wyman says, for example, that Easton fought hard for them to receive as big a fee as possible. Wyman cites an example of Bromley Court, who, in their early days, refused to pay £30 for an obscure band. After the Stones had become well known, the venue telephoned Easton back, wishing to book the group: "Eric said the price was now £300". Months later, the same venue enquired for the third time, by which point Easton set the price at £800. The group were never to play there.[177] Easton later said, in an interview, that Wyman's biography was the "most factual and truest history that's been written about the Stones because it's based on his extensive, personal diaries—his bleeding archives. Bill's an immaculate record keeper, so he actually knows more about the band's history than anyone".[160]

- ^ Easton also acted as engineer.[180]

- ^ Later released on the album Got Live If You Want It!.[180]

- ^ Released in the US as England's Newest Hitmakers.[128]

References

[edit]- ^ O'Sullivan 1974, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Covach & Boone 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Harper & Porter 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Gracyk 2001, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Gambaccini, Rice & Rice 1991, pp. 331–332.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Davis 2001.

- ^ Solly 2020.

- ^ Coopey 2010.

- ^ Frith 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2016, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sandford 2012, p. 51.

- ^ a b Dowley 1983, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Oldham 2011, p. 175.

- ^ Radio Times 1953, p. 41.

- ^ Radio Times 1948, p. 23.

- ^ Radio Times 1952, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e f Forget 2003, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Clayson 2007, p. 157.

- ^ Norman 2012, p. 96.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 132.

- ^ Stage 1963, p. 215.

- ^ a b Paytress 2005.

- ^ Oldham 2011, p. 93.

- ^ Nelson 2010, p. 20.

- ^ Goodman 2015, p. 86.

- ^ Schulps 1978.

- ^ Norman 2012, p. 99.

- ^ a b Lysaght 2003, p. 47.

- ^ Oldham 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Rej 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Oldham 2011, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Trynka 2015.

- ^ Jagger et al. 2003, p. 60.

- ^ a b c d e f Oldham 2011, p. 195.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rusten 2018, p. 14.

- ^ a b Dowley 1983, p. 28.

- ^ Sandford 2012, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Jagger et al. 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Norman 2012, p. 113.

- ^ a b Covach 2019, p. 15 n.13.

- ^ Norman 1984, p. 92.

- ^ McMillian 2013, p. 243 n.34.

- ^ a b Norman 2012, p. 117.

- ^ Cohen 2016, p. 54.

- ^ a b Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f Black 1995.

- ^ Lysaght 2003, p. 51.

- ^ Jackson 1992, p. 65.

- ^ a b Goodman 2015, p. 87.

- ^ a b Clayson 2007, p. 159.

- ^ Sanchez 2010, p. 35.

- ^ a b Oldham 2011, p. 204.

- ^ Norman 1984, p. 98.

- ^ a b Norman 1984, p. 93.

- ^ a b Norman 2012, p. 101.

- ^ a b c Goodall 1995, p. 31.

- ^ Dowley 1983, p. 29.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 134.

- ^ Norman 1984, p. 95.

- ^ Johns 2014, p. 39.

- ^ Norman 2012, p. 119.

- ^ Larkin2011, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d e Goodman 2015, p. 90.

- ^ Sandford 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Goodman 2015, p. 89.

- ^ Cott 1975, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Booth 2014.

- ^ Sandford 2012, p. 59.

- ^ Clayson 2007, p. 210.

- ^ Clayson 2007, p. 172.

- ^ Sandford 2012, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Nichols 1990b, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f Dunn 1984, p. 1D.

- ^ Andersen 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990.

- ^ Norman 2012, p. 182.

- ^ a b Norman 2012, p. 183.

- ^ a b Norman 1984, p. 101.

- ^ a b c Oldham 2011, p. 230.

- ^ Oldham 2011, pp. 230–231.

- ^ Norman 1984, pp. 99, 101.

- ^ a b Jackson 1992, pp. 72, 77.

- ^ Hotchner 1994, p. 99.

- ^ Booth 1984, p. 104.

- ^ Norman 1984, p. 100.

- ^ Clayson 2007, p. 174.

- ^ Independent 2013.

- ^ Oldham 2011, pp. 209–210, 212.

- ^ Coral, Hinckley & Rodman 1995.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 161.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2016, p. 30.

- ^ Thompson 2008, p. 55.

- ^ a b Goodman 2015, p. 95.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 146.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 244.

- ^ a b Goodman 2015, p. 104.

- ^ Mundy 1999, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Richards 2010, p. 77.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 215.

- ^ a b c Norman 1984, p. 124.

- ^ Cohen 2016, p. 55.

- ^ a b Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 229.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 231.

- ^ a b c Goodman 2015, p. 100.

- ^ Kellett 2017, p. 135.

- ^ Altham 1965.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 241.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 250.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 256.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 262.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 271.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 283.

- ^ a b Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 327.

- ^ Richards 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 40.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 337.

- ^ a b Oldham 2011, p. 269.

- ^ Nelson 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 168.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 245.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 330.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 334.

- ^ a b Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 336.

- ^ Clayson 2007, p. 183.

- ^ Goodman 2015, p. 105.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 339.

- ^ a b c d e Weiner 1983, p. 29.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 340.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 466.

- ^ Norman 2011, p. 376.

- ^ a b Goodman 2015, p. 80.

- ^ a b Clayson 2007, p. 251.

- ^ Goodman 2015, pp. 138–141.

- ^ Goodman 2015, pp. 144–151.

- ^ a b Birmingham Daily Post 1968, p. 11.

- ^ Schaffner 1983, p. 63.

- ^ Bockris 2006, p. 53.

- ^ Norman 1984, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Goodman 2015, p. 107.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, pp. 471–472.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 504.

- ^ a b c Goodman 2015, p. 149.

- ^ Norman 1984, p. 159.

- ^ Norman 1984, p. 271.

- ^ a b c Dunn 1984, p. 3D.

- ^ Jackson 1992, p. 115.

- ^ Goodman 2015, pp. 149–150.

- ^ a b Fornatale 2013, p. 51.

- ^ Clerk 2005.

- ^ Stage 1968, p. 231.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 532.

- ^ Weiner 1983, p. 52.

- ^ Norman 2012, p. 81.

- ^ Irish Times 2018.

- ^ Sandford 1998, p. 29.

- ^ a b Oldham 2011, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Clayson 2007, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Betts 2006, p. 351.

- ^ a b c d e Nichols 1991, p. 62.

- ^ a b Oldham 2011, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Nichols 1989b, p. 65.

- ^ Nichols 1989a, p. 49.

- ^ Downey 2011, p. 106.

- ^ Karnbach & Bernson 1997, p. 50.

- ^ a b Oldham 2011, p. 197.

- ^ Munn 1999, p. 21.

- ^ a b Clayson 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Carr 1990, p. 23.

- ^ McMillian 2013, p. 246 n.47.

- ^ Greenfield 1975, p. 36.

- ^ Thompson 1995.

- ^ McMillian 2013, p. 34.

- ^ Jagger et al. 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Norman 2012, p. 327.

- ^ a b Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 156.

- ^ Wyman & Coleman 1990, p. 186.

- ^ Nichols 1990a, p. 55.

- ^ Weiner 1983, pp. 82, 98.

- ^ a b c Weiner 1983, p. 38.

- ^ a b Miles 1980, p. 6.

- ^ Booth 1984, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Miles 1980, p. 7.

Bibliography

[edit]- Altham, K. (1965). "Startling Stones Discovery!". Rock's Back Pages. New Musical Express. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Andersen, C. (2012). Mick: The Wild Life and Mad Genius of Jagger. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-45166-144-6.

- Betts, G. (2006). Complete UK Hit Singles 1952–2006. London: Collins. ISBN 978-0-00720-077-1.

- Black, J. (May 1995). "The Rolling Stones: How It Happened". Q Magazine. OCLC 918387269.

- Birmingham Daily Post (3 October 1968). "Everybody is Suing Everybody–Counsel". Birmingham Daily Post. OCLC 1080828265.

- Bockris, V. (2006). Keith Richards: The Unauthorised Biography. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-846-1.

- Booth, S. (1984). Dance With the Devil: The Rolling Stones and Their Times. London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-39453-488-6.

- Booth, S. (2014). The True Adventures of the Rolling Stones (reprint ed.). Edinburgh: Canongate Books. ISBN 978-0-85786-352-2.

- Carr, E. (25 October 1990). "Bill's Story Carved in Stones". Evening Herald. OCLC 1026448276.

- Clayson, A. (2007). The Rolling Stones: The Origin of the Species: How, Why and Where It All Began. New Malden: Chrome Dreams. ISBN 978-1-84240-389-1.

- Clayson, A. (2008). The Rolling Stones: Beggars Banquet. New York: Flame Tree. ISBN 978-1-84451-296-6.

- Clerk, C. (2005). "Brian Jones: Death of a Rolling Stone". Rock's Back Pages. Uncut. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Cohen, R. (2016). The Sun and the Moon and the Rolling Stones. London: Headline. ISBN 978-1-47221-801-8.

- Coopey, R. (2010). "Popular Imperialism: The British Pop Music Business 1950 - 1975". Erasmus Research Institute of Management. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Coral, G.; Hinckley, D.; Rodman, D. (1995). The Rolling Stones: Black and White Blues. Atlanta, GA: Turner Publishing. ISBN 978-1-57036-150-0.

- Covach, J.; Boone, G. M. (1997). Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19535-662-5.

- Cott, J. (1975). "The Rolling Stone Interview: Mick Jagger". Rolling Stone. pp. 6–11. OCLC 645835566.

- Covach, J. (2019). "The Rolling Stones: Albums and Singles, 1963–1974". In Coelho, V.; Covach, J. (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to the Rolling Stones. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–15. ISBN 978-1-10703-026-8.

- Davis, S. (2001). Old Gods Almost Dead: The 40-Year Odyssey of the Rolling Stones. New York: Crown. ISBN 978-0-76790-956-3.

- Dowley, T. (1983). The Rolling Stones. London: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-85936-234-4.

- Downey, L. (8 January 2011). "Bonita Studio Attracts World of Music Talent". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Dunn, M. (5 January 1984). "The Man who got the Stones Rolling". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Forget, T. (2003). The Rolling Stones. New York: The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-82393-644-1.

- Fornatale, P. (2013). 50 Licks: Myths and Stories from Half a Century of the Rolling Stones. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-40883-382-7.

- Frith, S. (2010). "Analysing Live Music in the UK: Findings, One Year into a Three-year Research Project". IASPM Journal. I: 1–30. doi:10.5429/335. OCLC 44928449.

- Gambaccini, P.; Rice, T.; Rice, J. (1991). British Hit Singles: Every Single Hit Since 1952. Enfield: Guinness. ISBN 978-0-82307-572-0.

- Goodall, N. (1995). Jump Up—The Rise of the Rolling Stones: The First Ten Years: 1963–1973. London: Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 978-1-84989-377-0.

- Goodman, F. (2015). Allen Klein: The Man who Bailed Out the Beatles, Made the Stones, and Transformed Rock & Roll. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-54789-686-1.

- Gracyk, T. (2001). I Wanna be Me: Rock Music and the Politics of Identity. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-56639-903-6.

- Greenfield, R. (1975). "The Rolling Stone Interview: Keith Richards". Rolling Stone. pp. 32–61. OCLC 645835566.

- Harper, S.; Porter, V. (2003). British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19815-934-6.

- Hotchner, A. E. (1994). Blown Away. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-67171-542-7.

- Independent (7 June 2013). "Come On! The Rolling Stones Mark 50 Years since Debut Single with Rare Live Rendition". Independent. OCLC 768577259. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Irish Times (23 July 2018). "David Bowie's First Demo which was Found in a Bread Basket to be Sold". Irish Times. OCLC 33397137. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 4 March 2020.

- Jackson, L. (1992). Golden Stone: The Untold life and Mysterious Death of Brian Jones. New York: Smith Gryphon. ISBN 978-1-85685-030-8.

- Jagger, M.; Richards, K.; Loewenstein, D.; Watts, C.; Dodd, D.; Wood, R. (2003). According to the Rolling Stones. New York: Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-81184-060-6.

- Johns, G. (2014). Sound Man: A Life Recording Hits with The Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Eagles , Eric Clapton, The Faces... New York: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-10161-465-5.

- Karnbach, J.; Bernson, C. (1997). It's Only Rock 'n' Roll: The Ultimate Guide to the Rolling Stones. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-81603-035-4.

- Kellett, A. (2017). The British Blues Network: Adoption, Emulation, and Creativity. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-47203-699-8.

- Larkin, C. (2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-595-8.

- Lysaght, A. (2003). The Rolling Stones: An Oral History. Toronto: McArthur. ISBN 978-1-55278-392-4.

- McMillian, J. (2013). Beatles Vs. Stones. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-43915-969-9.

- Margotin, P.; Guesdon, J-M. (2016). The Rolling Stones All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track. New York: Hachette. ISBN 978-0-31631-773-3.

- Miles, Barry (1980). The Rolling Stones: An Illustrated Discography. London: Omnibus. ISBN 978-0-86001-762-2.

- Mundy, J. (1999). Popular Music on Screen: From the Hollywood Musical to Music Video. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-71904-029-9.

- Munn, L. (5 May 1999). "Daily Planner". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Nelson, M. R. (2010). The Rolling Stones: A Musical Biography. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-31338-034-1.

- Nichols, B. (15 November 1989a). "Rumor Mill Says: Rolling Stones Coming to Town". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Nichols, B. (30 November 1989b). "Manilow Magic?". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Nichols, B. (17 November 1990a). "Naples Businessman Nurtured Roots of Rock 'n' Roll". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Nichols, B. (1 July 1990b). "Naples Businessman Nurtured Roots of Rock 'n' Roll". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Nichols, B. (28 June 1991). "Man who Discovered Stones Unsurprised by No.1 Ranking". The News-Press. OCLC 1379240.

- Norman, P. (1984). Symphony for the Devil: The Rolling Stones Story. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-67144-975-9.

- Norman, P. (2011). Shout!: The Beatles in Their Generation. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-74325-378-9.

- Norman, P. (2012). Mick Jagger. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00732-953-3.

- O'Sullivan, D. (1974). The Youth Culture. London: Methuen. ISBN 978-0-42349-550-8.

- Oldham, A. L. (2011). Rolling Stoned. London: Gegensatz Press. ISBN 978-1-93323-784-8.

- Paytress, M. (2005). Rolling Stones: Off The Record. london: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-85712-113-4.

- Radio Times (9 July 1948). "The Week in the Regions". Radio Times. OCLC 70908951. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Radio Times (9 May 1952). "Light Programme". Radio Times. OCLC 70908951. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Radio Times (27 September 1953). "Light Programme". Radio Times. OCLC 70908951. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Rej, B. (2008). The Rolling Stones: In the Beginning. New York: Firefly. ISBN 978-1-78472-700-0.

- Richards, K. (2010). Life. London: Orion. ISBN 978-0-29785-862-1.

- Rusten, I. M. (2018). The Rolling Stones in Concert, 1962–1982: A Show-by-Show History. London: McFarland. ISBN 978-1-47663-443-2.

- Sanchez, T. (2010). Up and Down with The Rolling Stones: My Rollercoaster Ride with Keith Richards (2nd ed.). New York: John Blake Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85782-689-0.

- Sandford, C. (1998). Bowie: Loving the Alien. New York: Plenuum. ISBN 978-0-30680-854-8.

- Sandford, C. (2012). The Rolling Stones: Fifty Years. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-85720-102-7.

- Schaffner, N. (1983). The British Invasion: From the First Wave to the New Wave. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07055-089-6.

- Schulps, D. (1978). "Andrew Loog Oldham". Rock's Back Pages. Trouser Press. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Solly, R. (2020). "Britain Rocked Before The Beatles". Record Collector. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- Stage (1963). The Stage Year Book 1963. London: Carson & Comerford. OCLC 867861938.

- Stage (1968). The Stage Year Book 1967. London: Carson and Comerfod. OCLC 867862190.

- Thompson, D. (1995). "Andrew Loog Oldham: The Rolling Stones' First Manager And Producer". Rock's Back Pages. Goldmine. Archived from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- Thompson, G. (2008). Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19988-724-8.

- Trynka, P. (2015). Brian Jones: The Making of the Rolling Stones. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14751-645-9.

- Weiner, S. (1983). The Rolling Stones A to Z. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-39462-000-8.

- Wyman, B.; Coleman, R. (1990). Stone Alone: The Story of a Rock 'n' Roll Band. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-67082-894-4.