Nitrosamine

Nitrosamines (or more formally N-nitrosamines) are organic compounds produced by industrial processes.[1]

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: source better than a US state's regulations. (December 2024) |

The chemical structure is R2N−N=O, where R is usually an alkyl group.[2] They feature a nitroso group (NO+) that are "probable human carcinogens",[3] bonded to a deprotonated amine. Most nitrosamines are carcinogenic in animals.[4] A 2006 systematic review supports a "positive association between nitrite and nitrosamine intake and gastric cancer, between meat and processed meat intake and gastric cancer and oesophageal cancer, and between preserved fish, vegetable and smoked food intake and gastric cancer, but is not conclusive".[5]

Chemistry

[edit]

The organic chemistry of nitrosamines is well developed with regard to their syntheses, their structures, and their reactions.[7][8] They usually are produced by the reaction of nitrous acid (HNO2) and secondary amines, although other nitrosyl sources (e.g. N

2O

4, NOCl, RONO) have the same effect:[9]

- HONO + R2NH → R2N-NO + H2O

The nitrous acid usually arises from protonation of a nitrite. This synthesis method is relevant to the generation of nitrosamines under some biological conditions.[10] The nitrosation is also reversible, particularly in acidic solutions of nucleophiles.[11] Aryl nitrosamines rearrange to give a para-nitroso aryl amine in the Fischer-Hepp rearrangement.[12]

With regards to structure, the C2N2O core of nitrosamines is planar, as established by X-ray crystallography. The N-N and N-O distances are 132 and 126 pm, respectively in dimethylnitrosamine,[13] one of the simplest members of a large class of N-nitrosamines

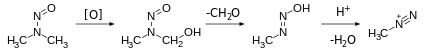

Nitrosamines are not directly carcinogenic. Metabolic activation is required to convert them to the alkylating agents that modify bases in DNA, inducing mutations. The specific alkylating agents vary with the nitrosamine, but all are proposed to feature alkyldiazonium centers.[14][6]

History and occurrence

[edit]In 1956, two British scientists, John Barnes and Peter Magee, reported that a simple member of the large class of N-nitrosamines, dimethylnitrosamine, produced liver tumours in rats. Subsequent studies showed that approximately 90% of the 300 nitrosamines tested were carcinogenic in a wide variety of animals.[15]

Tobacco exposure

[edit]A common way ordinary consumers are exposed to nitrosamines is through tobacco use and cigarette smoke.[14] Tobacco-specific nitrosamines also can be found in American dip snuff, chewing tobacco, and to a much lesser degree, snus (127.9 ppm for American dip snuff compared to 2.8 ppm in Swedish snuff or snus).[16]

Dietary exposure

[edit]Nitroso compounds react with primary amines in acidic environments to form nitrosamines, which human metabolism converts to mutagenic diazo compounds. Small amounts of nitro and nitroso compounds form during meat curing; the toxicity of these compounds preserves the meat against bacterial infection. After curing completes, the concentration of these compounds appears to degrade over time. Their presence in finished products has been tightly regulated since several food-poisoning cases in the early 20th century,[17] but consumption of large quantities of processed meats can still cause a slight elevation in gastric and oesophageal cancer risk today.[18][19][20][21]

For example, during the 1970s, certain Norwegian farm animals began exhibiting elevated levels of liver cancer. These animals had been fed herring meal preserved with sodium nitrite. The sodium nitrite had reacted with dimethylamine in the fish and produced dimethylnitrosamine.[22]

The effects of nitroso compounds vary dramatically across the gastrointestinal tract, and with diet. Nitroso compounds present in stool do not induce nitrosamine formation, because stool has neutral pH.[23][24] Stomach acid does cause nitrosamine compound formation, but the process is inhibited when amine concentration is low (e.g. a low-protein diet or no fermented food). The process may also be inhibited in the case of high vitamin C (ascorbic acid) concentration (e.g. high-fruit diet).[25][26][27] However, when 10% of the meal is fat, the effect reverses, and ascorbic acid markedly increases nitrosamine formation.[28][29]

Medication impurities

[edit]There have been recalls for various medications due to the presence of nitrosamine impurities. There have been recalls for angiotensin II receptor blockers, ranitidine, valsartan, Duloxetine, and others.

The US Food and Drug Administration published guidance about the control of nitrosamine impurities in medicines.[30][31] Health Canada published guidance about nitrosamine impurities in medications[32] and a list of established acceptable intake limits of nitrosamine impurities in medications.[33]

Examples

[edit]| Substance name | CAS number | Synonyms | Molecular formula | Physical appearance | Carcinogenity category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N-Nitrosonornicotine | 16543-55-8 | NNN | C9H11N3O | Light yellow low-melting solid | |

| 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone[34] | 64091-91-4 | NNK, 4′-(nitrosomethylamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone | C10H15N3O2 | Light yellow oil | |

| N-Nitrosodimethylamine | 62-75-9 | Dimethylnitrosamine, N,N-dimethylnitrosamine, NDMA, DMN | C2H6N2O | Yellow liquid | EPA-B2; IARC-2A; OSHA carcinogen; TLV-A3 |

| N-Nitrosodiethylamine | 55-18-5 | Diethylnitrosamide, diethylnitrosamine, N,N-diethylnitrosamine, N-ethyl-N-nitrosoethanamine, diethylnitrosamine, DANA, DENA, DEN, NDEA | C4H10N2O | Yellow liquid | EPA-B2; IARC-2A |

| 4-(Methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanol | 76014-81-8 | NNAL | |||

| N-Nitrosoanabasine | 37620-20-5 | NAB | C10H13N3O | Yellow Oil | IARC-3 |

| N-Nitrosoanatabine | 71267-22-6 | NAT | C10H11N3O | Clear yellow-to-orange oil | IARC-3 |

See also

[edit]- Hydrazines derived from these nitrosamines, e.g. UDMH, are also carcinogenic.

- Possible health hazards of pickled vegetables

- Tobacco-specific nitrosamines

Additional reading

[edit]- Altkofer, Werner; Braune, Stefan; Ellendt, Kathi; Kettl-Grömminger, Margit; Steiner, Gabriele (2005). "Migration of nitrosamines from rubber products - are balloons and condoms harmful to the human health?". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 49 (3): 235–238. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200400050. PMID 15672455.

- Proctor, Robert N. (2012). Golden Holocaust: Origins of the Cigarette Catastrophe and the Case for Abolition. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520950436. OCLC 784884555.

References

[edit]- ^ California Water Boards, State Water Resources Control Board, "Nitrosamines", 09 December 2024

- ^ Beard, Jessica C.; Swager, Timothy M. (21 January 2021). "An Organic Chemist's Guide to N-Nitrosamines: Their Structure, Reactivity, and Role as Contaminants". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 86 (3): 2037–2057. doi:10.1021/acs.joc.0c02774. PMC 7885798. PMID 33474939.

- ^ World Health Organisation, Medical product alert, Note on Nitrosamine impurities, "Update on Nitrosamine impurities", 20 November 2019

- ^ Yang, Chung S.; Yoo, Jeong-Sook H.; Ishizaki, Hiroyuki; Hong, Junyan (1990). "Cytochrome P450IIe1: Roles in Nitrosamine Metabolism and Mechanisms of Regulation". Drug Metabolism Reviews. 22 (2–3): 147–159. doi:10.3109/03602539009041082. PMID 2272285.

- ^ Jakszyn, Paula; Gonzalez, Carlos (2006). "Nitrosamine and related food intake and gastric and oesophageal cancer risk: A systematic review of the epidemiological evidence". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (27): 4296–4303. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i27.4296. PMC 4087738. PMID 16865769.

- ^ a b Tricker, A.R.; Preussmann, R. (1991). "Carcinogenic N-Nitrosamines in the Diet: Occurrence, Formation, Mechanisms and Carcinogenic Potential". Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology. 259 (3–4): 277–289. doi:10.1016/0165-1218(91)90123-4. PMID 2017213.

- ^ Anselme, Jean-Pierre (1979). "The Organic Chemistry of N-Nitrosamines: A Brief Review". N-Nitrosamines. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 101. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1021/bk-1979-0101.ch001. ISBN 0-8412-0503-5.

- ^ Vogel, A. I. (1962). Practical Organic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Impression. p. 1074.

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, pp. 846–847, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ Williams 1988, p. 142.

- ^ Williams, D. L. H. (1988). Nitrosation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University. pp. 128–139. ISBN 0-521-26796-X.

- ^ Smith, Michael B.; March, Jerry (2007), Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, p. 739, ISBN 978-0-471-72091-1

- ^ Krebs, Bernt; Mandt, Jürgen (1975). "Kristallstruktur des N-Nitrosodimethylamins". Chemische Berichte. 108 (4): 1130–1137. doi:10.1002/cber.19751080419.

- ^ a b Hecht, Stephen S. (1998). "Biochemistry, Biology, and Carcinogenicity of Tobacco-Specific N-Nitrosamines". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 11 (6): 559–603. doi:10.1021/tx980005y. PMID 9625726.

- ^ Advances in Agronomy. Academic Press. 2013-01-08. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-12-407798-0.

- ^ Gregory N. Connolly; Howard Saxner (August 21, 2001). "Informational Update Research on Tobacco Specific Nitrosamines (TSNAs) in Oral Snuff and a Request to Tobacco Manufacturers to Voluntarily Set Tolerance Limits For TSNAs in Oral Snuff".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Honikel, K. O. (2008). "The use an control of nitrate and nitrite for the processing of meat products" (PDF). Meat Science. 78 (1–2): 68–76. doi:10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.05.030. PMID 22062097.

- ^ Lunn, J.C.; Kuhnle, G.; Mai, V.; Frankenfeld, C.; Shuker, D.E.G.; Glen, R. C.; Goodman, J.M.; Pollock, J.R.A.; Bingham, S.A. (2006). "The effect of haem in red and processed meat on the endogenous formation of N-nitroso compounds in the upper gastrointestinal tract". Carcinogenesis. 28 (3): 685–690. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl192. PMID 17052997.

- ^ Bastide, Nadia M.; Pierre, Fabrice H.F.; Corpet, Denis E. (2011). "Heme Iron from Meat and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Meta-analysis and a Review of the Mechanisms Involved". Cancer Prevention Research. 4 (2): 177–184. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0113. PMID 21209396. S2CID 4951579.

- ^ Bastide, Nadia M.; Chenni, Fatima; Audebert, Marc; Santarelli, Raphaelle L.; Taché, Sylviane; Naud, Nathalie; Baradat, Maryse; Jouanin, Isabelle; Surya, Reggie; Hobbs, Ditte A.; Kuhnle, Gunter G.; Raymond-Letron, Isabelle; Gueraud, Françoise; Corpet, Denis E.; Pierre, Fabrice H.F. (2015). "A Central Role for Heme Iron in Colon Carcinogenesis Associated with Red Meat Intake". Cancer Research. 75 (5): 870–879. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2554. PMID 25592152. S2CID 13274953.

- ^ Jakszyn, P; Gonzalez, CA (2006). "Nitrosamine and related food intake and gastric and oesophageal cancer risk: A systematic review of the epidemiological evidence". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 12 (27): 4296–4303. doi:10.3748/wjg.v12.i27.4296. PMC 4087738. PMID 16865769.

- ^ Joyce I. Boye; Yves Arcand (2012-01-10). Green Technologies in Food Production and Processing. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 573. ISBN 978-1-4614-1586-2.

- ^ Lee, L; Archer, MC; Bruce, WR (October 1981). "Absence of volatile nitrosamines in human feces". Cancer Res. 41 (10): 3992–4. PMID 7285009.

- ^ Kuhnle, GG; Story, GW; Reda, T; et al. (October 2007). "Diet-induced endogenous formation of nitroso compounds in the GI tract". Free Radic. Biol. Med. 43 (7): 1040–7. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.011. PMID 17761300.

- ^ Mirvish, SS; Wallcave, L; Eagen, M; Shubik, P (July 1972). "Ascorbate–nitrite reaction: possible means of blocking the formation of carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds". Science. 177 (4043): 65–8. Bibcode:1972Sci...177...65M. doi:10.1126/science.177.4043.65. PMID 5041776. S2CID 26275960.

- ^ Mirvish, SS (October 1986). "Effects of vitamins C and E on N-nitroso compound formation, carcinogenesis, and cancer". Cancer. 58 (8 Suppl): 1842–50. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19861015)58:8+<1842::aid-cncr2820581410>3.0.co;2-#. PMID 3756808. S2CID 196379002.

- ^ Tannenbaum SR, Wishnok JS, Leaf CD (1991). "Inhibition of nitrosamine formation by ascorbic acid". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 53 (1 Suppl): 247S–250S. Bibcode:1987NYASA.498..354T. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb23774.x. PMID 1985394. S2CID 41045030. Retrieved 2015-06-06.

Evidence now exists that ascorbic acid is a limiting factor in nitrosation reactions in people.

- ^ Combet, E.; Paterson, S; Iijima, K; Winter, J; Mullen, W; Crozier, A; Preston, T; McColl, K. E. (2007). "Fat transforms ascorbic acid from inhibiting to promoting acid-catalysed N-nitrosation". Gut. 56 (12): 1678–1684. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.128587. PMC 2095705. PMID 17785370.

- ^ Combet, E; El Mesmari, A; Preston, T; Crozier, A; McColl, K. E. (2010). "Dietary phenolic acids and ascorbic acid: Influence on acid-catalyzed nitrosative chemistry in the presence and absence of lipids". Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 48 (6): 763–771. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.12.011. PMID 20026204.

- ^ "Control of Nitrosamine Impurities in Human Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 24 February 2021.

- ^ https://www.fda.gov/media/141720/download [bare URL]

- ^ "Nitrosamine impurities in medications: Guidance". Health Canada. 4 April 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Nitrosamine impurities in medications: Established acceptable intake limits". Health Canada. 15 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Hecht, Steven S.; Borukhova, Anna; Carmella, Steven G. "Tobacco specific nitrosamines" Chapter 7; of "Nicotine safety and toxicity" Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco; 1998 - 203 pages