Portal (video game)

| Portal | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Valve[a] |

| Publisher(s) | Valve |

| Designer(s) | Kim Swift |

| Writer(s) | |

| Composer(s) | |

| Series | Portal |

| Engine | Source |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Puzzle-platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Portal is a 2007 puzzle-platform game developed and published by Valve. It was released in a bundle, The Orange Box, for Windows, Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3, and has been since ported to other systems, including Mac OS X, Linux, Android (via Nvidia Shield), and Nintendo Switch.

Portal consists primarily of a series of puzzles that must be solved by teleporting the player's character and simple objects using "the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device", also referred to as the "portal gun", a device that can create intra-spatial portals between two flat planes. The player-character, Chell, is challenged and taunted by an artificial intelligence named GLaDOS (Genetic Lifeform and Disk Operating System) to complete each puzzle in the Aperture Science Enrichment Center using the portal gun with the promise of receiving cake when all the puzzles are completed. The Source Engine's physics system allows kinetic energy to be retained through portals, requiring creative use of portals to maneuver through the test chambers. This gameplay element is based on a similar concept from the game Narbacular Drop; many of the team members from the DigiPen Institute of Technology who worked on Narbacular Drop were hired by Valve for the creation of Portal, making it a spiritual successor to the game.

Portal was acclaimed as one of the most original games of 2007, despite some criticism for its short duration. It received praise for its originality, unique gameplay and a dark story and sense of comedy. GLaDOS, voiced by Ellen McLain in the English-language version, received acclaim for her unique characterization, and the end credits song "Still Alive", written by Jonathan Coulton for the game, was praised for its original composition and humor. Portal is often cited as one of the greatest video games ever made. Excluding Steam download sales, over four million copies of the game have been sold since its release, spawning official merchandise from Valve including a model portal gun and plush Companion Cubes, as well as fan recreations of the cake.

A standalone version with extra puzzles, Portal: Still Alive, was also published by Valve on the Xbox Live Arcade service in October 2008 exclusively for Xbox 360. A sequel, Portal 2, was released in 2011, which expanded on the storyline, added several gameplay mechanics, and included a cooperative multiplayer mode. A port for the Nintendo Switch was released as part of the Portal: Companion Collection in June 2022.

Gameplay

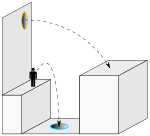

[edit]In Portal, the player controls the protagonist, Chell, from a first-person perspective as she is challenged to navigate through a series of test chambers using the Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device, or portal gun, under the supervision of the artificial intelligence GLaDOS. The portal gun can create two distinct portal ends, orange and blue. The portals create a visual and physical connection between two different locations in three-dimensional space. Neither end is specifically an entrance or exit; all objects that travel through one portal will exit through the other. An important aspect of the game's physics is momentum redirection and conservation.[4] As moving objects pass through portals, they come through the exit portal at the same direction that the exit portal is facing and with the same speed with which they passed through the entrance portal.[5] For example, a common maneuver is to place a portal some distance below the player on the floor, jump down through it, gaining speed in freefall, and emerge through the other portal on a wall, flying over a gap or another obstacle. This process of gaining speed and then redirecting that speed towards another area of a puzzle allows the player to launch objects or Chell over great distances both vertically and horizontally. This is referred to as 'flinging' by Valve.[4] As GLaDOS puts it, "In layman's terms: speedy thing goes in, speedy thing comes out." If portal ends are not on parallel planes, the character passing through is reoriented to be upright with respect to gravity after leaving a portal end.

Chell and all other objects in the game that can fit into the portal ends will pass through the portal. However, a portal shot cannot pass through an open portal; it will simply fizzle or create a new portal in an offset position. Creating a portal end instantly fizzles an existing portal end of the same color. Moving objects, glass, non-white surfaces, liquids, or areas that are too small will not be able to anchor portals. Chell is often provided with cubes that she can pick up and use to climb on or to place on large buttons that open doors or activate mechanisms. Particle fields, known as "Emancipation Grills", occasionally called "Fizzlers" in the developer commentary, exist at the end of all and within some test chambers; when passed through, they will deactivate (fizzle) any active portals and disintegrate any object carried through. These fields also block attempts to fire portals through them.[6]

Although Chell is equipped with mechanized heel springs to prevent damage from falling,[4] she can be killed by various other hazards in the test chambers, such as turrets, bouncing balls of energy, and toxic liquid. She can also be killed by objects hitting her at high speeds, and by a series of crushers that appear in certain levels. Unlike most action games at the time, there is no health indicator; Chell dies if she is dealt a certain amount of damage in a short period, but returns to full health fairly quickly. Some obstacles, such as the energy balls and crushing pistons, deal fatal damage with a single blow.

Many solutions exist for completing each puzzle.[7] Two additional modes are unlocked upon the completion of the game that challenge the player to work out alternative methods of solving each test chamber. Challenge chambers are unlocked near the halfway point and Advanced Chambers are unlocked when the game is completed.[8] In Challenge chambers, levels are revisited with the added goal of completing the test chamber either with as little time, with the fewest portals, or with the fewest footsteps possible. In Advanced chambers, certain levels are made more complex with the addition of more obstacles and hazards.[9][10]

Synopsis

[edit]Characters

[edit]The game features two characters: the player-controlled silent protagonist named Chell, and GLaDOS (Genetic Lifeform and Disk Operating System), a computer artificial intelligence that monitors and directs the player. In the English-language version, GLaDOS is voiced by Ellen McLain, though her voice has been altered to sound more artificial. The only background information presented about Chell is given by GLaDOS; the credibility of these facts, such as Chell being adopted, an orphan, and having no friends, is questionable at best, as GLaDOS is a liar by her own admission. In the "Lab Rat" comic created by Valve to bridge the gap between Portal and Portal 2, Chell's records reveal she was ultimately rejected as a test subject for having "too much tenacity"—the main reason Doug Rattman, a former employee of Aperture Science, moved Chell to the top of the test queue.[11][12]

Setting

[edit]

Portal takes place in the Half-Life universe and inside of Aperture Science Laboratories Computer-Aided Enrichment Center, a research facility responsible for the creation of the portal gun. Information about Aperture Science, developed by Valve for creating the setting of the game, is revealed during the game and via the real-world promotional website.[13] According to the Aperture Science website, Cave Johnson founded the company in 1943 for the sole purpose of making shower curtains for the U.S. military. However, after becoming mentally unstable from "moon rock poisoning" in 1978, Johnson created a three-tier research and development plan to make his organization successful. The first two tiers, the Counter-Heimlich Maneuver (a maneuver designed to ensure choking) and the Take-A-Wish Foundation (a program to give the wishes of terminally ill children to adults in need of dreams), were commercial failures and led to an investigation of the company by the U.S. Senate. However, when the investigative committee heard of the success of the third tier—a person-sized, ad hoc quantum tunnel through physical space, with a possible application as a shower curtain—it recessed permanently and gave Aperture Science an open-ended contract to continue its research. The development of GLaDOS, an artificially intelligent research assistant and disk-operating system, began in 1986 in response to Black Mesa's work on similar portal technology.[14]

A presentation seen during gameplay reveals that GLaDOS was also included in a proposed bid for de-icing fuel lines, incorporated as a fully functional disk-operation system that is arguably alive, unlike Black Mesa's proposal, which inhibits ice, nothing more.[15] Roughly thirteen years later, work on GLaDOS was completed and the untested AI was activated during the company's bring-your-daughter-to-work day in May 2000.[13] Immediately after activation, the facility was flooded with deadly neurotoxin by the AI. Events of the first Half-Life game occur shortly after that, presumably leaving the facility forgotten by the outside world due to apocalyptic happenings. Wolpaw, in describing the ending of Portal 2, affirmed that the Combine invasion, chronologically taking place after Half-Life and before Half-Life 2, had occurred before Portal 2's events.[16]

The areas of the Enrichment Center that Chell explores suggest that it is part of a massive research installation. At the time of events depicted in Portal, the facility seems to be long-deserted, although most of its equipment remains operational without human control.[17]

Plot

[edit]The game begins with Chell waking up from a stasis bed and hearing instructions from GLaDOS, an artificial intelligence, about upcoming tests. Chell enters into sequential distinct chambers that introduce her to varying challenges to solve using her portal gun, with GLaDOS as her only interaction.[4] GLaDOS promises cake as a reward for Chell if she completes all the test chambers.[18] As Chell nears completion, GLaDOS's motives and behavior turn more sinister, suggesting insincerity and callous disregard for the safety and well-being of test subjects. The test chambers become increasingly dangerous as Chell proceeds, including a live-fire course designed for military androids, as well as chambers flooded with a hazardous liquid. In one chamber, GLaDOS forces Chell to "euthanize" a Weighted Companion Cube in an incinerator, after Chell uses it for assistance.[17][19][20]

After Chell completes the final test chamber, GLaDOS maneuvers Chell into an incinerator in an attempt to kill her. Chell escapes with the portal gun and makes her way through the maintenance areas within the Enrichment Center.[21] GLaDOS panics and insists that she was pretending to kill Chell as part of testing, while it becomes clear that GLaDOS had previously killed all the inhabitants of the center.[11][12] Chell travels further through the maintenance areas, discovering dilapidated backstage areas covered in graffiti that includes statements such as "the cake is a lie", and pastiches of quotes from famous poets such as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Emily Brontë.[4]

Despite GLaDOS's attempts to dissuade her with lies and threats, Chell proceeds and eventually confronts GLaDOS in a large chamber where her hardware hangs overhead. A sphere soon falls from GLaDOS and Chell drops it in an incinerator. GLaDOS reveals that the sphere was the morality core of her conscience, one of multiple personality cores that Aperture Science employees installed after she flooded the center with neurotoxin gas; with the core removed, she can access its emitters again. A six-minute countdown starts as Chell dislodges and incinerates more of GLaDOS' personality cores, while GLaDOS mocks and attacks her. After Chell destroys the last personality core, a malfunction tears the room apart and transports everything to the surface. Chell lies outside the facility's gates amid the remains of GLaDOS, but is promptly dragged away by an unseen robotic entity.[b]

The final scene, viewed within the bowels of the facility, shows a candlelit Black Forest cake,[23] and a Weighted Companion Cube, surrounded by shelves containing dozens of inactive personality cores. The cores begin to light up, before a robotic arm descends and extinguishes the candle on the cake, casting the room into darkness.[24] Over the credits, GLaDOS delivers a concluding report through the song "Still Alive", declaring the experiment to be a success.[25]

Development

[edit]Narbacular Drop

[edit]Portal began with the 2005 freeware game Narbacular Drop, developed by students of the DigiPen Institute of Technology.[26][27] Robin Walker, one of Valve's developers, saw the game at the DigiPen's career fair. Impressed, he contacted the team with advice and offered to show their game at Valve's offices. After their presentation, Valve's president Gabe Newell offered the team jobs at Valve to develop the game further.[28] Newell said he was impressed with the team as "they had actually carried the concept through", already having included the interaction between portals and physics, completing most of the work that Valve would have had to commit on their own.[28]

To test the effectiveness of the portal mechanic, the team made a prototype in an in-house 2D game engine that is used in DigiPen.[29] Certain elements were retained from Narbacular Drop, such as the system of identifying the two unique portal endpoints with the colors orange and blue. A key difference is that Portal's portal gun cannot create a portal through an existing portal, unlike in Narbacular Drop. The original setting, of a princess trying to escape a dungeon, was dropped in favor of the Aperture Science approach.[28] Portal took approximately two years and four months to complete after the DigiPen team was brought into Valve,[30] and no more than ten people were involved with its development.[31]

Story

[edit]For the first year of development, the team focused mostly on the gameplay without narrative structure. Playtesters found the game fun but asked about what these test chambers were leading towards. This prompted the team to come up with a narrative for Portal.[32]

The team worked with Marc Laidlaw, the writer of the Valve's Half-Life series, to fit Portal into the Half-Life universe.[33] This was done in part because of the project's limited art resources; instead of creating new art assets for Portal, the team reused the Half-Life 2 assets.[15] Laidlaw opposed the crossover, feeling it "made both universes smaller", and said later: "I just had to react as gracefully as I could to the fact that it was going there without me. It didn't make any sense except from a resource-restricted point of view."[34]

Valve hired Erik Wolpaw and Chet Faliszek to write Portal. Wolpaw felt that the constraints improved the game.[35] The concept of a computer AI guiding the player through experimental facilities to test the portal gun was arrived at early in the writing process.[15] They drafted early lines for the yet-named "polite" AI with humorous situations, such as requesting the player's character to "assume the party escort submission position", and found this style of approach to be well-suited to the game they wanted to create, leading to the creation of the GLaDOS character.[15] GLaDOS was central to the plot. Wolpaw said: "We designed the game to have a very clear beginning, middle, and end, and we wanted GLaDOS to go through a personality shift at each of these points."[36]

Wolpaw described the idea of using cake as the reward came about as "at the beginning of the Portal development process, we sat down as a group to decide what philosopher or school of philosophy our game would be based on. That was followed by about 15 minutes of silence and then someone mentioned that a lot of people like cake."[15][36] The cake element, along with additional messages given to the player in the behind-the-scenes areas, were written and drawn by Kim Swift.[37]

Design

[edit]

The austere settings in the game came about because testers spent too much time trying to complete the puzzles using decorative but non-functional elements. As a result, the setting was minimized to make the usable aspects of the puzzle easier to spot, using the clinical feel of the setting in the film The Island as reference.[38] While there were plans for a third area, an office space, to be included after the test chambers and the maintenance areas, the team ran out of time to include it.[38] They also dropped the introduction of the Rat Man, a character who left the messages in the maintenance areas, to avoid creating too much narrative for the game,[39] though the character was developed further in a tie-in comic "Lab Rat", that ties Portal and Portal 2's story together.[11][12] According to project lead Kim Swift, the final battle with GLaDOS went through many iterations, including having the player chased by James Bond lasers, which was partially applied to the turrets, Portal Kombat where the player would have needed to redirect rockets while avoiding turret fire, and a chase sequence following a fleeing GLaDOS. Eventually, they found that playtesters enjoyed a rather simple puzzle with a countdown timer near the end; Swift noted, "Time pressure makes people think something is a lot more complicated than it really is", and Wolpaw admitted, "It was really cheap to make [the neurotoxin gas]" in order to simplify the dialogue during the battle.[31]

Chell's face and body are modeled after Alésia Glidewell, an American freelance actress and voice-over artist, selected by Valve from a local modeling agency for her face and body structure.[30][40] Ellen McLain provided the voice of the antagonist GLaDOS. Erik Wolpaw noted, "When we were still fishing around for the turret voice, Ellen did a sultry version. It didn't work for the turrets, but we liked it a lot, and so a slightly modified version of that became the model for GLaDOS's final incarnation."[36]

The Weighted Companion Cube inspiration was from project lead Kim Swift with additional input from Wolpaw from reading some "declassified government interrogation thing" whereby "isolation leads subjects to begin to attach to inanimate objects";[31][36] Swift commented, "We had a long level called Box Marathon; we wanted players to bring this box with them from the beginning to the end. But people would forget about the box, so we added dialogue, applied the heart to the cube, and continued to up the ante until people became attached to the box. Later on, we added the incineration idea. The artistic expression grew from the gameplay."[38] Wolpaw further noted that the need to incinerate the Weighted Companion Cube came as a result of the final boss battle design; they recognized they had not introduced the idea of incineration necessary to complete the boss battle, and by training the player to do it with the Weighted Companion Cube, found the narrative "way stronger" with its "death".[41] Swift noted that any similarities to psychological situations in the Milgram experiment or 2001: A Space Odyssey are entirely coincidental.[38]

The portal gun's full name, Aperture Science Handheld Portal Device, can be abbreviated as ASHPD, which resembles a shortening of the name Adrian Shephard, the protagonist of Half-Life: Opposing Force. Fans noticed this similarity before the game's release; as a result, the team placed a red herring in the game by having the letters of Adrian Shephard highlighted on keyboards found within the game.[38] According to Kim Swift, the cake is a Black Forest cake that she thought looked the best at the nearby Regent Bakery and Cafe in Redmond, Washington, and, as an Easter egg within the game, its recipe is scattered among various screens showing lines of binary code.[23][42] The Regent Bakery has stated that since the release of the game, its Black Forest cake has been one of its more popular items.[42]

Soundtrack

[edit]Most of the soundtrack is non-lyrical ambient music composed by Kelly Bailey and Mike Morasky, somewhat dark and mysterious to match the mood of the environments. The closing credits song, "Still Alive", was written by Jonathan Coulton and sung by Ellen McLain (a classically trained operatic soprano) as the GLaDOS character. A brief instrumental version of "Still Alive" is played in an uptempo Latin style over radios in-game. Wolpaw notes that Coulton was invited to Valve a year before the release of Portal, though it was not yet clear where Coulton would contribute. "Once Kim [Swift] and I met with him, it quickly became apparent that he had the perfect sensibility to write a song for GLaDOS."[25][36] The use of the song over the closing credits was based on a similar concept from the game God Hand, one of Wolpaw's favorite titles.[43] The song was released as a free downloadable song for the music video game Rock Band on April 1, 2008.[44][45][46] The soundtrack for Portal was released as a part of The Orange Box Original Soundtrack.[47]

The soundtrack was released in a four-disc retail bundle, Portal 2: Songs To Test By (Collector's Edition), on October 30, 2012, featuring music from both games.[48] The soundtrack was released via Steam Music on September 24, 2014.[49]

Release

[edit]Portal was first released as part of The Orange Box for Windows and Xbox 360 on October 10, 2007,[50][51] and for the PlayStation 3 on December 11, 2007.[52] The Windows version of the game is also available for download separately through Valve's content delivery system, Steam,[1] and was released as a standalone retail product on April 9, 2008.[53] In addition to Portal, the Box also included Half-Life 2 and its two add-on episodes, as well as Team Fortress 2. Portal's inclusion within the Box was considered an experiment by Valve; having no idea of the success of Portal, the Box provided it a "safety net" via means of these other games. Portal was kept to a modest length in case the game did not go over well with players.[24]

In January 2008, Valve released a special demo version titled Portal: The First Slice, free for any Steam user using Nvidia graphics hardware as part of a collaboration between the two companies.[54] It also comes packaged with Half-Life 2: Deathmatch, Peggle Extreme, and Half-Life 2: Lost Coast. The demo includes test chambers 00 to 10 (eleven in total). Valve has since made the demo available to all Steam users.[55]

Portal is the first Valve-developed game to be added to the OS X-compatible list of games available on the launch of the Steam client for Mac on May 12, 2010,[56] supporting Steam Play, in which buying the game on Macintosh or Windows computer makes it playable on both. As part of the promotion, Portal was offered as a free game for any Steam user during the two weeks following the Mac client's launch.[57] Within the first week of this offer, over 1.5 million copies of the game were downloaded through Steam.[58] A similar promotion was held in September 2011, near the start of a traditional school year, encouraging the use of the game as an educational tool for science and mathematics.[59][60] Valve wrote that they felt that Portal "makes physics, math, logic, spatial reasoning, probability, and problem-solving interesting, cool, and fun", a necessary feature to draw children into learning.[61] This was tied to Digital Promise, a United States Department of Education initiative to help develop new digital tools for education, and which Valve is part of.[62]

Portal: Still Alive was announced as an exclusive Xbox Live Arcade game at the 2008 E3 convention, and was released on October 22, 2008.[63] It features the original game, 14 new challenges, and new achievements.[64] The additional content was based on levels from the map pack Portal: The Flash Version created by We Create Stuff and contains no additional story-related levels.[65] According to Valve spokesman Doug Lombardi, Microsoft had previously rejected Portal on the platform due to its large size.[66] Portal: Still Alive was well received by reviewers.[67] 1UP.com's Andrew Hayward stated that, with the easier access and lower cost than paying for The Orange Box, Portal is now "stronger than ever".[68] IGN editor Cam Shea ranked it fifth on his top 10 list of Xbox Live Arcade games. He stated that it was debatable whether an owner of The Orange Box should purchase this, as its added levels do not add to the plot. However, he praised the quality of the new maps included in the game.[69] The game ranked 7th in a later list of top Xbox Live Arcade titles compiled by IGN's staff in September 2010.[70] Additionally, Portal: Still Alive got ported to the Nintendo Switch as a part of The Companion Collection.

During 2014 GPU Technology Conference on March 25, 2014, Nvidia announced a port of Portal to the Nvidia Shield, their Android handheld;[71] the port was released on May 12, 2014.[72] Alongside Portal 2, Portal was released on the Nintendo Switch on June 28, 2022, as part of Portal: Companion Collection, developed by Valve and Nvidia Lightspeed Studios.[73][74] Nvidia announced Portal With RTX, a remaster intended to show off the functionality of the company's GeForce 40 series graphics cards with real-time path tracing,[75] for release as a free DLC, initially planned for November 2022. It was released on December 8, 2022.[76]

Reception

[edit]Critical reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | PC: 90/100[77] X360 (Still Alive): 90/100[78] PC (RTX): 89/100[79] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| 1Up.com | A[17] |

| Eurogamer | 9/10[19] |

| GameSpot | 9.0/10 |

| GameSpy | 4.5/5.0[18] |

| IGN | 8.2/10[20] |

Portal received critical acclaim, often earning more praise than either Half-Life 2: Episode Two or Team Fortress 2, two titles also included in The Orange Box. It was praised for its unique gameplay and dark, deadpan humor.[80] Eurogamer cited that "the way the game progresses from being a simple set of perfunctory tasks to a full-on part of the Half-Life story is absolute genius",[81] while GameSpy noted, "What Portal lacks in length, it more than makes up for in exhilaration."[82] The game was criticized for sparse environments, and both criticized and praised for its short length.[83] Aggregate reviews for the standalone PC version of Portal gave the game a 90/100 through 28 reviews on Metacritic.[77] In 2011, Valve stated that Portal had sold more than four million copies through the retail versions, including the standalone game and The Orange Box, and from the Xbox Live Arcade version.[84]

The game generated a fan following for the Weighted Companion Cube[85]—even though the cube itself does not talk or act in the game. Fans have created plush[86] and papercraft versions of the cube and the various turrets,[87] as well as PC case mods[88] and models of the Portal cake and portal gun.[89][90][91] Jeep Barnett, a programmer for Portal, noted that players have told Valve that they had found it more emotional to incinerate the Weighted Companion Cube than to harm one of the "Little Sisters" from BioShock.[38] Both GLaDOS and the Weighted Companion Cube were nominated for the Best New Character Award on G4, with GLaDOS winning the award for "having lines that will be quoted by gamers for years to come."[92][93][94] Ben Croshaw of Zero Punctuation praised the game as "absolutely sublime from start to finish ... I went in expecting a slew of interesting portal-based puzzles and that's exactly what I got, but what I wasn't expecting was some of the funniest pitch black humor I've ever heard in a game". He felt the short length was ideal as it did not outstay its welcome.[95]

Writing for GameSetWatch in 2009, columnist Daniel Johnson pointed out similarities between Portal and Erving Goffman's essay on dramaturgy, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, which equates one's persona to the front and backstage areas of a theater.[96] The game was also made part of the required course material among other classical and contemporary works, including Goffman's work, for a freshman course "devoted to engaging students with fundamental questions of humanity from multiple perspectives and fostering a sense of community" for Wabash College in 2010.[97][98] Portal has also been cited as a strong example of instructional scaffolding that can be adapted for more academic learning situations, as the player, through careful design of levels by Valve, is first hand-held in solving simple puzzles with many hints at the correct solution, but this support is slowly removed as the player progresses in the game, and completely removed when the player reaches the second half of the game.[99] Rock, Paper, Shotgun's Hamish Todd considered Portal as an exemplary means of game design by demonstrating a series of chambers after the player has obtained the portal gun that gently introduce the concept of flinging without any explicit instructions.[100] Portal was exhibited at the Smithsonian Art Exhibition in America from February 14 through September 30, 2012. Portal won the "Action" section for the platform "Modern Windows".[101]

Since its release Portal is still considered one of the best video games of all time, having been included on several cumulative "Top Games of All Time" lists through 2018.[102][103][104]

Awards

[edit]Portal won several awards:

- During the 11th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences awarded Portal with Outstanding Achievement in Gameplay Engineering, Outstanding Achievement in Game Design, and Outstanding Character Performance for Ellen McLain's vocal portrayal of GLaDOS;[105] as part of The Orange Box compilation, it also won Computer Game of the Year (shared with Half-Life 2: Episode Two and Team Fortress 2).[106]

- At the 2008 Game Developers Choice Awards, Portal won Game of the Year award, along with the Innovation Award and Best Game Design award.[107]

- IGN honored Portal with several awards, for Best Puzzle Game for PC[108] and Xbox 360,[109] Most Innovative Design for PC,[110] and Best End Credit Song (for "Still Alive") for Xbox 360,[111] along with overall honors for Best Puzzle Game[112] and Most Innovative Design.[113]

- In its Best of 2007, GameSpot honored The Orange Box with 4 awards in recognition of Portal, giving out honors for Best Puzzle Game,[114] Best New Character(s) (for GLaDOS),[115] Funniest Game,[116] and Best Original Game Mechanic (for the portal gun).[117]

- Portal was awarded Game of the Year (PC), Best Narrative (PC), and Best Innovation (PC and console) honors by 1UP.com in its 2007 editorial awards.[118]

- GamePro honored the game for Most Memorable Villain (for GLaDOS) in its Editors' Choice 2007 Awards.[119]

- Portal was awarded the Game of the Year award in 2007 by Joystiq,[120] Good Game,[121] and Shacknews.[122]

- The Most Original Game award by X-Play.[123]

- In Official Xbox Magazine's 2007 Game of the Year Awards, Portal won Best New Character (for GLaDOS), Best Original Song (for "Still Alive"), and Innovation of the Year.[124]

- In GameSpy's 2007 Game of the Year awards, Portal was recognized as Best Puzzle Game,[125] Best Character (for GLaDOS), and Best Sidekick (for the Weighted Companion Cube).[125]

- The A.V. Club called it the Best Game of 2007.[126]

- The webcomic Penny Arcade awarded Portal Best Soundtrack, Best Writing, and Best New Game Mechanic in its satirical 2007 We're Right Awards.[127]

- Eurogamer gave Portal first place in its Top 50 Games of 2007 rankings.[128]

- IGN also placed GLaDOS, (from Portal) as the No. 1 Video Game Villain on its Top-100 Villains List.[129]

- GamesRadar named it the best game of all time.[130]

- In November 2012, Time named it one of the 100 greatest video games of all time.[131]

- Wired considered Portal to be one of the most influential games of the first decade of the 21st century, believing it to be a prime example of quality over quantity for video games.[132]

Legacy

[edit]

The popularity of the game and its characters led Valve to develop merchandise for Portal made available through its online Valve physical merchandise store. Some of the more popular items were the Weighted Companion Cube plush toys and fuzzy dice.[133] When first released, both were sold out in under 24 hours.[134] Other products available through the Valve store include T-shirts and Aperture Science coffee mugs and parking stickers, and merchandise relating to the phrase "the cake is a lie", which has become an internet meme. Wolpaw noted they did not expect certain elements of the game to be as popular as they were, while other elements they had expected to become fads were ignored, such as a giant hoop that rolls on-screen during the final scene of the game that the team had named Hoopy.[15][135]

Swift stated that future Portal developments would depend on the community's reactions, saying, "We're still playing it by ear at this point, figuring out if we want to do multiplayer next, or Portal 2, or release map packs."[9] Some rumors regarding a sequel arose due to casting calls for voice actors.[136][137] On March 10, 2010, Portal 2 was officially announced for a release late in that year;[138] the announcement was preceded by an alternate reality game based on unexpected patches made to Portal that contained cryptic messages in relation to Portal 2's announcement, including an update to the game, creating a different ending for the fate of Chell. The original game left her in a deserted parking lot after destroying GLaDOS, but the update involved Chell being dragged back into the facility by a "Party Escort Bot". Though Portal 2 was originally announced for a Q4 2010 release, the game was released on April 19, 2011.[22][139][140][141]

A modding community has developed around Portal, with users creating their own test chambers and other in-game modifications.[142][143] The group "We Create Stuff" created an Adobe Flash version of Portal, titled Portal: The Flash Version, just before release of The Orange Box. This flash version was well received by the community[144] and the group has since converted it to a map pack for the published game.[145] Another mod, Portal: Prelude, is an unofficial prequel developed by an independent team of three that focuses on the pre-GLaDOS era of Aperture Science, and contains nineteen additional "crafty and challenging" test chambers.[146][147] An ASCII version of Portal was created by Joe Larson.[148][149] An unofficial port of Portal to the iPhone using the Unity game engine was created but only consisted of a single room from the game.[150][151] Mari0 is a fan-made four-player coop mashup of the original Super Mario Bros. and Portal.[152]

An unofficial port for the Nintendo 64 console titled Portal 64 was under development.[c] By September 2023, the programmer had a working copy but still had ways to go to be completely finished.[160] The project was taken down in January 2024 due to a request by Valve; according to the main developer, the port's reliance on "Nintendo's proprietary libraries" was the reason.[161][162]

Film adaptation

[edit]A film adaptation has been in development hell since 2013, and it was reported on May 25, 2021, that the project is still in development by J.J. Abrams and Bad Robot and the script has been written.[163] As of 2022, J.J. Abrams continued to express interest in bringing Portal to the big screen.[164]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Nvidia Lightspeed Studios developed the Nvidia Shield, Nintendo Switch versions and the RTX mod version for Windows.

- ^ The game's original ending does not include the entity taking Chell, and was retroactively included following the announcement of Portal 2.[15][22]

- ^ Attributed to multiple sources:[153][154][155][156][157][158][159]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Portal". Steam. Valve. Archived from the original on August 10, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Paul, Jason (May 12, 2014). "The Greatest PC Games of All-Time – Half-Life 2 and Portal – Now Available on SHIELD". NVIDIA Corporation. TegraZone. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 11, 2014.

- ^ "Portal". Google Apps. May 12, 2014. Archived from the original on May 13, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Valve (October 9, 2007). Portal. Level/area: In-game developer commentary.

- ^ Alessi, Jeremy (August 26, 2008). "Games Demystified: Portal". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on August 7, 2010. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ^ The Orange Box manual (Xbox 360 version). Valve. 2007. pp. 12–17.

- ^ Ocampo, Jason (July 13, 2006). "Half-Life 2: Episode Two — The Return of Team Fortress 2 and Other Surprises". GameSpot. Archived from the original on March 23, 2014. Retrieved July 21, 2006.

- ^ Craddock, David (October 3, 2007). "Portal: Final Hands-on". IGN. Archived from the original on April 15, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ^ a b Bramwell, Tom (May 15, 2007). "Portal: First Impressions". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 28, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ^ Francis, Tom (May 9, 2007). "PC Preview: Portal— PC Gamer Magazine". ComputerAndVideoGames.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- ^ a b c Esposito, Joey (April 8, 2011). "Portal 2: Lab Rat – Part 1". IGN. Archived from the original on April 10, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ a b c Esposito, Joey (April 11, 2011). "Read Portal 2: Lab Rat – Part 2". IGN. Archived from the original on April 13, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ a b VanBurkleo, Meagan (March 24, 2010). "Aperture Science: A History". Game Informer. Archived from the original on March 27, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ "Aperture Science Web Site (login: cjohnson password: tier3)". Valve. Archived from the original on September 17, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reeves, Ben (March 10, 2010). "Exploring Portal's Creation And Its Ties To Half-Life 2". Game Informer. Archived from the original on March 14, 2010. Retrieved March 10, 2010.

- ^ Stanton, Rich (April 26, 2011). "Erik Wolpaw on Portal 2's ending: "the [spoiler] is probably lurking out there somewhere"". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on April 30, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c Elliot, Shawn (October 10, 2007). "Portal (PC)". 1UP. Archived from the original on June 25, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ^ a b Accardo, Sal (October 9, 2007). "Portal (PC)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on January 5, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ a b Bradwell, Tom (October 10, 2007). "Portal". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on August 10, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ a b Adams, Dan (October 9, 2007). "Portal Review". IGN. Archived from the original on March 10, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ Montfort, Nick (2009). "Portal of Ivory, Passage of Horn". In Drew Davidson; et al. (eds.). Well Played 1.0: Video Game, Value and Meaning. ETC Press. ISBN 978-0-557-06975-0. Archived from the original on January 8, 2010. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Faylor, Chris (March 3, 2010). "Portal Mystery Deepens with Second Update". Shacknews. Archived from the original on March 5, 2010. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Geoff, Keighley (March 1, 2008). "GameTrailers Episode 106". GameTrailers.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ a b VanBurkleo, Meagan (April 2010). "Portal 2". Game Informer. pp. 50–62.

- ^ a b Coulton, Jonathan (October 15, 2007). "Portal: The Skinny". Jonathan Coulton's blog. Archived from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved November 1, 2007.

- ^ "Things are heating up!". Narbacular Drop official site. July 17, 2006. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved July 21, 2006.

- ^ Berghammer, Billy (August 25, 2006). "GC 06:Valve's Doug Lombardi Talks Half-Life 2 Happenings". Game Informer. Archived from the original on October 2, 2007. Retrieved September 27, 2007.

- ^ a b c Dudley, Breir (April 17, 2011). "'Portal' backstory a real Cinderella tale". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on April 20, 2011. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ Portal Problems - Lecture 11 - CS50's Introduction to Game Development 2018. YouTube. CS50. May 4, 2018. Event occurs at 27:45. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Pratt (September 30, 2007). "Pratt and Chief interview the Portal team at VALVe headquarters". Planet Half-Life. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c Faylor, Chris (February 23, 2008). "GDC 08: Portal Creators on Writing, Multiplayer, Government Interrogation Techniques". Shacknews. Archived from the original on August 14, 2009. Retrieved February 23, 2008.

- ^ Roberts, Samuel (October 10, 2017). "Valve reflects on The Orange Box, ten years later". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Leone, Matt (September 8, 2006). "Portal Preview". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved September 11, 2006.

- ^ Peel, Jeremy (March 1, 2023). "'The narrative had to be baked into the corridors': Marc Laidlaw on writing Half-Life". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on March 2, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ Irwin, Mary Jane (February 23, 2008). "GDC: A Portal Postmortem". Next-Gen Biz. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved February 26, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Walker, John (October 31, 2007). "RPS Interview: Valve's Erik Wolpaw". Rock Paper Shotgun. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ Pinchefsky, Carol (June 26, 2012). "Kim Swift, Creator of 'Portal,' Discusses Her Latest Game, 'Quantum Conundrum'". Forbes. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved June 26, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Elliot, Shawn (February 6, 2008). "Beyond the Box: Orange Box Afterthoughts". 1UP. Archived from the original on December 6, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (February 23, 2008). "Portal Devs Reveal the GLaDOS That Never Was, Inspiration Behind Weighted Companion Cube". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 26, 2008. Retrieved February 26, 2008.

- ^ Glidewell, Alésia. "On-Camera — Alésia Glidewell — Voice Over Artist". AlesiaGlidewell.com. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Graff, Kris (November 2, 2009). "Valve's Writers And The Creative Process". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on November 5, 2009. Retrieved November 2, 2009.

- ^ a b VanBurkleo, Meagan (March 31, 2010). "Let There Be Cake". Game Informer. Archived from the original on April 2, 2010. Retrieved March 31, 2010.

- ^ Turi, Tim (September 1, 2012). "Chell Almost Married A Turret In Portal 2". Game Informer. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Baptiste, Sean (February 21, 2008). "Valve Party at GDC + Special Preview of an Upcoming DLC Song". Harmonix. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Baptiste, Sean. "DLC April 1st! Huge success!". Rockband.com forums. Archived from the original on April 2, 2008. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ Faylor, Chris (March 31, 2008). "'Still Alive' Hits Rock Band X360 Tomorrow for Free, PlayStation 3 Edition Due Mid-April". Shacknews. Archived from the original on April 2, 2008. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ "The Orange Box Original Soundtrack". Valve. Archived from the original on December 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Hinkle, David (September 24, 2012). "Portal 2: Songs to Test By (Collectors Edition) out on Oct. 30". Joystiq. Archived from the original on November 25, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ "Introducing the Steam Music Player". Steam. Valve. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ "The Orange Box (PC)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 18, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "The Orange Box (Xbox 360)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 18, 2009. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ "The Orange Box (PS3)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 18, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ Kiestmann, Ludwig (March 6, 2008). "Individual Orange Box games hit retail April 9". Joystiq. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ "Valve and NVIDIA Offer Portal: First Slice Free to GeForce Users". Steam. Valve. January 9, 2008. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ "Everyday Shooter Makes PC Debut on Steam Today". Valve. May 8, 2008. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

In other Steam news, Portal: First Slice – the official demo for the title named Game of the Year by over 30 publications – is now available for free to all gamers via Steam.

- ^ Hollister, Sean (April 29, 2010). "Steam for Mac Opens a Portal to May 12, steps through". Engadget. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Caolli, Eric (May 12, 2010). "Steam Launched For Mac, Portal Offered For Free". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on May 13, 2010. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Remo, Chris (May 19, 2010). "Portal Racks Up 1.5M Free Downloads On PC, Mac". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on May 21, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ Purchase, Robert (September 16, 2011). "Portal free on Steam until 20th Sept". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ "Learn With Portals". learningwithportals.com. Valve. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Kuchera, Ben (September 16, 2011). "Portal is used to teach science as Valve gives game away for limited time". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on September 23, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2011.

- ^ Toppo, Greg (September 19, 2011). "Valve teams with White House in digital learning program". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 21, 2011. Retrieved September 20, 2011.

- ^ Faylor, Chris (October 16, 2008). "Portal: Still Alive Hits Xbox Live Arcade Next Wed; Promises Cake and Companionship". Shacknews. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2008.

- ^ Faylor, Chris (July 14, 2008). "Portal: Still Alive Coming Exclusively to Xbox 360". Shacknews. Archived from the original on July 15, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

- ^ Remo, Chris (July 20, 2008). "Portal: Still Alive Explained". GameSetWatch. Archived from the original on July 29, 2008. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ Lee, James (April 28, 2008). "Portal was offered to XBLA, but rejected". GamesIndustry.biz. Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- ^ "Portal: Still Alive (xbox360: 2008)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 25, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ Hayward, Andrew (October 27, 2008). "Portal: Still Alive (Xbox 360)". 1UP. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ "IGN's Top 10 Xbox Live Arcade Games". IGN. May 7, 2009. Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- ^ "The Top 25 Xbox Live Arcade Games". IGN. September 16, 2010. Archived from the original on September 18, 2010. Retrieved September 16, 2010.

- ^ Paul, Jason (March 25, 2014). "What's in the Box? Portal – Valve's Popular PC Title – Coming to SHIELD". Nvidia. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ Tach, Dave (May 26, 2014). "Why Nvidia created its own hardware platform and started developing games". Polygon. Vox Media. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ Carpenter, Nicole (February 9, 2022). "Portal and Portal 2 coming to Nintendo Switch". Polygon. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Phillips, Tom (February 9, 2022). "Portal and Portal 2 coming to Nintendo Switch". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on February 9, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2022.

- ^ Roach, Jacob (December 6, 2022). "Why Portal RTX is the most demanding game I've ever tested". Digital Trends. Retrieved March 17, 2024.

- ^ Middler, Jordan (September 20, 2022). "Nvidia is bringing ray-tracing to Portal with an RTX version". Video Games Chronicle. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b "Portal (pc: 2007): Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 28, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2007.

- ^ "Portal: Still Alive for Xbox 360 Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom. Archived from the original on August 17, 2010. Retrieved April 10, 2022.

- ^ "Portal with RTX for PC Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved December 16, 2022.

- ^ Keil, Matt. "G4 Review — The Orange Box". G4TV. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ Reed, Kristen (October 10, 2007). "The Orange Box". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on October 26, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ McGarvey, Sterline (October 10, 2007). "The Orange Box (X360)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

- ^ Adams, Dan. "IGN: Portal Review". IGN. Archived from the original on March 11, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ Rose, Mike (April 20, 2011). "Portal Sells 4 Million Excluding Steam Sale". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Alexander, Leigh (December 19, 2007). "Gamasutra's Best Of 2007: Top 5 Poignant Game Moments". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007. Retrieved December 19, 2007.

- ^ Jetlogs (October 29, 2007). "Companion Cube Plushie Sewing Pattern". Jetlogs. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Jetlogs (October 14, 2007). "Portal: Weighted Companion Cube Papercraft". Jetlogs. Archived from the original on February 4, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Persson, Magnus (January 28, 2008). "Weighted Companion Cube PC case mods". Bit-tech.net. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ Lizzie (January 1, 2008). "How to Make a Weighted Companion Cube Cake". Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved February 7, 2008.

- ^ de Marco, Flynn (October 21, 2007). "The Weighted Companion Cube Cake". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 2, 2008. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Cavali, Earnest (January 21, 2009). "Fan Crafts Gorgeous Replica Portal Gun". Wired. Archived from the original on May 2, 2009. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ "Winners of X-Play Best of 2007 Awards Announced—BioShock is Video Game of the Year". G4TV. December 17, 2007. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Neuls, Johnathan (November 12, 2007). "Valve to sell official Weighted Companion Cube plushies". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on April 19, 2008. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ^ Kurchera, Ben (January 2, 2008). "Kiss Me, Kill Me, Thrill Me: ups and downs in gaming 2007". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on August 29, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ^ "The Orange Box - Zero Punctuation Video Gallery - The Escapist". The Escapist. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- ^ Johnson, Daniel (June 1, 2009). "Column: 'Lingua Franca' – Portal and the Deconstruction of the Institution". GameSetWatch. Archived from the original on June 5, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ^ Goldman, Tom (August 22, 2010). "College Professor Requires Students to Study Portal". The Escapist. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Klepek, Patrick (May 18, 2011). "Intro to GLaDOS 101: A Professor's Decision to Teach Portal". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2011.

- ^ Schiller, Nicholas (2008). "A Portal to Student Learning: What Instruction Librarians can Learn from Video Game Design". Reference Services Review. 36 (4): 351–365. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.623.999. doi:10.1108/00907320810920333. ISSN 0090-7324. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2009.

- ^ Todd, Hamish (September 20, 2013). "Untold Riches: An Analysis Of Portal's Level Design". Rock Paper Shotgun. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 20, 2013.

- ^ "The Art of Video Games Exhibition Checklist" (PDF). Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian Institution. April 5, 2012. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2012. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ^ Polygon Staff (November 27, 2017). "The 500 Best Video Games of All Time". Polygon.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved December 1, 2017.

- ^ "The Top 300 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 300. April 2018.

- ^ "Top 100 Video Games of All Time". IGN. 2018. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "D.I.C.E. Awards By Video Game Details The Orange Box: Portal". interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "D.I.C.E. Awards By Video Game Details The Orange Box". interactive.org. Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved November 13, 2023.

- ^ "Portal BioShocks GDC Awards". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 4, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ "IGN Best of 2007: PC Best Puzzle Game". IGN. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "IGN Best of 2007: Xbox 360 – Best Puzzle Game". IGN. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "IGN Best of 2007: PC — Most Innovative Design". IGN. Archived from the original on October 16, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "IGN Best of 2007: Xbox 360 – Best End Credit Song". IGN. Archived from the original on February 26, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "IGN Best of 2007: Overall — Best Puzzle Game". IGN. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "IGN Best of 2007: Overall — Most Innovative Design". IGN. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "GameSpot's Best of 2007: Best Puzzle Game Genre Awards". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ "GameSpot's Best of 2007: Best New Character(s) Special Achievement". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ "GameSpot's Best of 2007". Pure Nintendo. 2007. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ "GameSpot's Best of 2007: Best Original Game Mechanic Special Achievement". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ "2007 1UP Network Editorial Awards from 1UP.com". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ The GamePros (December 27, 2007). "GamePro Editors' Choice *2007* (Pg. 2/5)". GamePro. Archived from the original on December 31, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ Kietzmann, Ludwig (January 1, 2008). "Joystiq's Top 10 of 2007: Portal". Joystiq. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ "Game of the Year". Good Game Stories. December 12, 2007. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ Shack Staff (January 4, 2008). "Game of the Year Awards 2007". Shacknews. Archived from the original on February 4, 2009. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "X-Play Best of 2007: Most Original Game". G4. December 18, 2007. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- ^ "OXM's 2007 Game of the Year Awards". Official Xbox Magazine. March 17, 2008. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- ^ a b "GameSpy's Game of the Year 2007: Special Awards". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ Dahlen, Chris; Mastrapa, Gus (December 24, 2007). "A. V. Club Best Games of 2007". A. V. Club. Archived from the original on December 29, 2008. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ^ "Penny Arcade! We're Right Returns". Penny Arcade. December 28, 2007. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved December 28, 2007.

- ^ "Eurogamer's Top 50 Games of 2007". Eurogamer. December 28, 2007. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved January 1, 2008.

- ^ "IGN's top 100 villains". IGN. May 14, 2010. Archived from the original on May 18, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- ^ GamesRadar Staff (February 25, 2015). "The 100 best games ever". GamesRadar. p. 12. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved October 4, 2018.

- ^ "All-TIME 100 Video Games". Time. Time Inc. November 15, 2012. Archived from the original on November 16, 2012. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ Kohler, Chris (December 24, 2009). "The 15 Most Influential Games of the Decade". Wired. Archived from the original on March 15, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- ^ "Steam Updates: Friday, November 9, 2007". Valve. November 9, 2007. Archived from the original on November 11, 2007. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ^ De Marco, Flynn (December 15, 2007). "Official Plush Weighted Companion Cube Sells Out". Kotaku. Archived from the original on March 4, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Davenport, James (October 10, 2017). "'The cake is a lie'—the life and death of Portal's best baked meme". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on October 10, 2017. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (June 10, 2008). "Casting call reveals Portal 2 details". Kotaku. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (June 10, 2008). "More details on Portal 2's bad guy". Kotaku. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved July 18, 2008.

- ^ Webster, Andrew (March 5, 2010). "Portal 2 is official, first image inside". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ Leahy, Brian (March 1, 2010). "Portal Patch Adds Morse Code, Achievement – Portal 2 Speculation Begins". Shacknews. Archived from the original on March 3, 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Mastrapa, Gus (March 2, 2010). "Geeky Clues Suggest Portal Sequel Is Coming". Wired. Archived from the original on March 3, 2010. Retrieved March 2, 2010.

- ^ Gaskill, Jake (March 3, 2010). "Rumor: Valve To Make Portal 2 Announcement During GDC 2010". X-Play. Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ Zitron, Ed (January 5, 2008). "Portal Maps Investigated". CVG. Archived from the original on January 7, 2008. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ "Thinking With Portals". ThinkingWithPortals.com. Archived from the original on August 30, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- ^ Peckham, Matt (October 11, 2007). "Portal: The Flash Version". PC World. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ Breckon, Nick (May 5, 2008). "Flash Version of Portal Converted to Actual Map Pack". Shacknews. Archived from the original on October 29, 2010. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ Cavalli, Earnest (October 8, 2008). "Portal: Prelude Now Available". Wired. Archived from the original on October 9, 2008. Retrieved October 9, 2008.

- ^ Phillips, John (September 22, 2009). "Portal: Prelude". GameSpy. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved December 18, 2008.

- ^ Plunkett, Luke (July 8, 2009). "It's Portal, Running In ASCII". Kotaku. Archived from the original on July 12, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ Larson, Joseph (January 12, 2011). "ASCIIportal | Cymonsgames". Joseph Larson. Archived from the original on December 29, 2010. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Spenser, Spanner (July 15, 2009). "Valve's Portal opened on the iPhone". Pocket Gamer. Archived from the original on July 18, 2009. Retrieved July 16, 2009.

- ^ Boyer, Brandon (July 16, 2009). "Chell's bells: Portal on the iPhone". Boing Boing Offworld. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved July 17, 2009.

- ^ McWhertor, Michael (August 29, 2011). "Mari0 Is What Happens When Mario Gets a Portal Gun". Kotaku. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ "Random: Portal 64 Demake Shows Portal Running on "Real N64 Hardware"". May 15, 2022. Archived from the original on May 15, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "Portal Ported: Fan Remakes Valve's Classic Puzzle Game for Nintendo 64". May 16, 2022. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "This Portal demake runs on actual Nintendo 64 hardware". May 16, 2022. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "Somehow, the N64 Can do Portal". May 16, 2022. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "Portal 'Demake' Will Find a Home on the Nintendo 64". May 16, 2022. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "This N64 Portal Demake Running on Real Hardware is Looking Promising". May 17, 2022. Archived from the original on May 17, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "This N64 demake of Portal shouldn't work, but it does". May 18, 2022. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ Stanton, Rich (September 5, 2023). "Legend has spent years making Portal for the N64 and by Gaben he's done it". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on November 20, 2023. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Bailey, Dustin (January 10, 2024). "After years of supporting mods and fan games, Valve takes action against Team Fortress and Portal fan projects". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Bailey, Kat (January 10, 2024). "Team Fortress: Source 2 and Portal 64 Fan Projects Shut Down by Valve Takedowns". IGN. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ^ Jorgensen, Tom (May 24, 2021). "Portal Movie Still Alive, in Development at Warner Bros., Says Producer JJ Abrams". IGN. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2022.

- ^ "8 Exciting Upcoming Projects J.J. Abrams Is Producing". Screen Rant. May 23, 2022. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Jeep Barnett, Kim Swift & Erik Wolpaw (November 4, 2008). "Thinking With Portals: Creating Valve's New IP". Gamasutra. CMP Media. Archived from the original on November 7, 2008. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

External links

[edit]- 2007 video games

- 3D platformers

- Android (operating system) games

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- First-person video games

- Game Developers Choice Award for Game of the Year winners

- Linux games

- MacOS games

- Mass murder in fiction

- Nintendo Switch games

- Fiction about physics

- Platformers

- PlayStation 3 games

- Portal (series)

- Puzzle-platformers

- Science fiction video games

- Single-player video games

- Source (game engine) games

- Spike Video Game Award winners

- Fiction about teleportation

- Valve Corporation games

- Video game memes

- Video games about artificial intelligence

- Video games developed in the United States

- Video games featuring female protagonists

- Video games scored by Kelly Bailey

- Video games scored by Mike Morasky

- Video games set in 2010

- Video games set in laboratories

- Video games set in Michigan

- Video games using Havok

- Video games with commentaries

- Windows games

- Xbox 360 games

- Xbox 360 Live Arcade games