Battle of Attu

| Battle of Attu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Aleutian Islands campaign | |||||||

U.S. soldiers fire mortar shells over a ridge onto a Japanese position on 4 June 1943 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 15,000[1] | 2,600 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

549 killed 1,148 wounded 1,814 frostbitten and sick[2] |

2,351 killed or committed suicide 28 captured ~200 missing or holding out[3] | ||||||

The Battle of Attu (codenamed Operation Landcrab),[4] which took place on 11–30 May 1943, was fought between forces of the United States, aided by Canadian reconnaissance and fighter-bomber support, and Japan on Attu Island off the coast of the Territory of Alaska as part of the Aleutian Islands campaign during the American Theater and the Pacific Theater. Attu is the only land battle in which Japanese and American forces fought in snowy conditions, in contrast with the tropical climate in the rest of the Pacific. The battle ended when most of the Japanese defenders were killed in brutal hand-to-hand combat after a final banzai charge broke through American lines.

Background

[edit]The strategic position of the islands of Attu and Kiska off Alaska's coast meant their locations could control the sea lanes across the northern Pacific Ocean. Japanese planners believed control of the Aleutians would therefore prevent any possible U.S. attacks from Alaska. This assessment had already been inferred by U.S. General Billy Mitchell who told the U.S. Congress in 1935, "I believe that in the future, whoever holds Alaska will hold the world. I think it is the most important strategic place in the world."[5]

On 7 June 1942, six months after the United States entered World War II, the 301st Independent Infantry Battalion from the Japanese Northern Army landed unopposed on Attu. The landings occurred one day after the invasion of nearby Kiska. The U.S. military feared both islands could be turned into strategic Japanese airbases from which aerial attacks could be launched against mainland Alaska and the rest of the U.S. West Coast.

In Walt Disney's 1943 film Victory Through Air Power, the use of the Aleutian Islands for American long-range bombers to bomb Japan was postulated.[6]

Recapture

[edit]

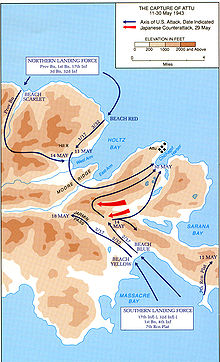

On 11 May 1943, units from 17th Infantry, of Major General Albert E. Brown's 7th U.S. Infantry Division made amphibious landings on Attu to retake the island from Japanese Imperial Army forces led by Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki. Despite heavy naval bombardments of Japanese positions, the American troops encountered strong entrenched defenses that made combat conditions tough. Arctic weather and exposure-related injuries also caused numerous casualties among U.S. forces. After two weeks of relentless fighting, however, American units managed to push the Japanese defenders back to a pocket around Chichagof Harbor.

On 21–22 May a powerful Japanese fleet assembled in Tokyo Bay in preparation for a sortie to repel the American attempt to recapture Attu. The fleet included the carriers Zuikaku, Shōkaku, Jun'yō, Hiyō, the battleships Musashi, Kongō, Haruna, and the cruisers Mogami, Kumano, Suzuya, Tone, Chikuma, Agano, Ōyodo, and eleven destroyers. The Americans, however, recaptured Attu before the fleet could depart.[7]

On 29 May, without hope of rescue, Yamasaki led his remaining troops in a banzai charge. The surprise attack broke through the American front line positions. Shocked American rear-echelon troops were soon fighting in hand-to-hand combat with Japanese soldiers. The battle continued until almost all of the Japanese were killed. The charge effectively ended the battle for the island, although U.S. Navy reports indicate that small groups of Japanese continued to fight until early July 1943,[citation needed] and isolated Japanese survivors held out until as late as 8 September 1943.[8] In 19 days of battle, 549 soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division were killed and more than 1,200 injured. The Japanese lost over 2,351 men, including Yamasaki; 28 prisoners were taken.[2]

Aftermath

[edit]Attu was the last action of the Aleutian Islands campaign. The Japanese Northern Army secretly evacuated its remaining garrison from nearby Kiska, ending the Japanese occupation in the Aleutian Islands on 28 July 1943.

The loss of Attu and the evacuation of Kiska came shortly after the death of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, who was killed by American aircraft in Operation Vengeance. These defeats compounded the demoralizing effect of losing Yamamoto on the Japanese High Command.[9] Despite the losses, Japanese propaganda attempted to present the Aleutian Island campaign as an inspirational epic.[9]

Reparations and the Exhumation of Soldiers

[edit]After the war, surviving Attuans were barred from returning to the island since the U.S. military believed it would be too costly to rebuild the island. The survivors were then relocated to Atka Island, about 200 miles away. The last former Attu captive died in 2023.[10]

In recent years there have been renewed calls for reparations. One individual leading these calls is Helena Pagano, an advocate for Attuan cultural preservation. Pagano’s great-grandfather was the last Alaska Native chief of Attu Island in the Bering Sea and he died of starvation as a prisoner of war after Japanese forces invaded. While Japan offered survivors $4,000 annually for three years in 1951, Pagano’s grandmother rejected the payment, deeming it insufficient for the suffering endured. Her call for justice reignited after a 2024 visit to Attu, where Japanese officials, as part of ongoing efforts to recover soldiers’ remains, exhumed two sets of human bones form a former Attu village site which is currently owned by the Aleut Corporation. Pagano's calls for reparations request not only further financial restitution but also the establishment of a cultural center for Attuans in Alaska, an environmental cleanup of wartime debris on Attu, and greater inclusion of Attuans in memorial efforts. Japanese government officials claim they have not received recent requests for additional restitution from Attuan descendants.

Efforts to recover the remains of Japanese soldiers who died during World War II have intensified as war veterans and their relatives age, with Japan incorporating DNA testing to aid in identification. Of the approximately 2.4 million Japanese troops who died outside Japan, the remains of just over half have been recovered. On Attu Island, Japan's first recovery mission took place in 1953, yielding the remains of about 320 soldiers, which were repatriated and stored at the Chidorigafuchi National Cemetery. Efforts to locate additional remains have faced delays, largely due to U.S. environmental regulations governing excavation activities on the island. In 2009, the U.S. required an environmental assessment, further postponing recovery operations for more than a decade.[11][12] During an August 2024 visit, limited excavation under U.S. supervision led to the recovery of two sets of human remains, believed to be Japanese soldiers. These remains were sent to Anchorage for preliminary evaluation, with plans to transfer samples to Japan for DNA testing if they are confirmed as likely Japanese.[13]

Order of battle

[edit]IJA 2nd District, North Seas Garrison (Hokkai Shubitai) – Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki[14][15]

- 83rd Independent Infantry Battalion – Lieutenant-Colonel Isamu Yonegawa

- 303rd Independent Infantry Battalion "Watanabe Battalion" – Major Jokuji Watanabe

- Aoto Provisional Anti-Aircraft Battalion – Major Seiji Aoto

- Northern Kurile Fortress Infantry Battalion – Lieutenant-Colonel Hiroshi Yonekawa

- 6th Independent Mountain Artillery – Second Lieutenant Taira Endo

- 302nd Independent Engineer Company – Captain Chinzo Ono

- 6th Ship Engineer Regiment

- 2nd Company – Captain Kobayashi

US Landing Force Attu (US 7th Infantry Division) – Major General Albert Brown, Brigadier General Eugene M. Landrum from 16 May[16][15]

- Provisional Scout Battalion – Captain William H. Willoughby

- 7th Scout Company

- 7th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop

- Northern Force – Colonel Frank L. Culin

- 1st/17th Regimental Combat Team – Lieutenant Colonel Albert V. Hartl

- Southern Force – Colonel Edward Palmer Earle †, Colonel Wayne C. Zimmerman from 12 May

- 2nd/17th Regimental Combat Team – Major Edward P. Smith

- 3rd/17th Regimental Combat Team – Major James R. Montague

- 2nd/32nd Regimental Combat Team – Major Charles G. Fredericks

- Reinforcements/Combat Support

- 1st/32nd Regimental Combat Team – Lieutenant Colonel Earnest H. Bearss

- 3rd/32nd Regimental Combat Team – Lieutenant Colonel John M. Finn

- 1st/4th Regimental Combat Team (at Adak) – Major John D. O'Reilly

- 78th Coast Artillery (Anti-Aircraft) Regiment

- 50th Combat Engineer Battalion

Gallery

[edit]

|

See also

[edit]- Aleutian Islands World War II National Monument

- Castner's Cutthroats, a specially-selected 65-man unit which performed reconnaissance missions in the Aleutian Islands during the Pacific War

- Japanese Occupation Site

- Joe P. Martínez, a posthumous Medal of Honor recipient for actions during the Battle of Attu

- Paul Nobuo Tatsuguchi, a Japanese Seventh Day Adventist who served as military surgeon on Attu and died during the fighting

References

[edit]- ^ a b "The Battle for Kiska", Canadianheroes.org, 13 May 2002,

Originally Published in Esprit de Corp Magazine, Volume 9 Issue 4 and Volume 9 Issue 5

- ^ a b "US National Park Service". Nps.gov.

- ^ "Battle of Attu: 60 Years Later (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov.

- ^ "Battle of Attu". The History Channel. 27 September 2023.

- ^ "Arctic Panel looks at the world from the top down". Army.mil. 6 November 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2022.

- ^ "Walt Disney's - Victory Through Air Power (1943, 720p) - YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ^ "Zuikaku Tabular Record of Movement (TROM)". Imperial Japanese Navy Page. Jonathan Parshall. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Herder, 2019, p.85

- ^ a b John Toland, The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936-1945 New York:Random House (1970) p. 444

- ^ Thiessen, Mark (9 December 2023). "Death of last surviving Alaskan taken by Japan during WWII rekindles memories of forgotten battle". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rall, Mary (8 September 2009). "Alaska Engineers further WWII recovery effort on Attu Island". US Army. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rudis, D.D. 2013. Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge – Attu and Kiska Islands Contaminant Assessment. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Juneau Field Office, Alaska. 146 pp

- ^ Thiessen, Mark; Yamaguchi, Mari (9 December 2024). "Descendant of last native leader of Alaska island demands Japanese reparations for 1942 invasion". Associated Press. Retrieved 16 December 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Cloe, 2017, pp.160–168

- ^ a b Herder, 2019, p.66

- ^ Cloe, 2017, pp.150–159

Further reading

[edit]- Cloe, John Haile (1990). The Aleutian Warriors: A History of the 11th Air Force and Fleet Air Wing 4. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co. and Anchorage Chapter – Air Force Association. ISBN 0-929521-35-8. OCLC 25370916.

- Cloe, John Haile (1990). Attu: The Forgotten Battle. United States Department of the Interior. ISBN 0-9965837-3-4. OCLC 25370916.

- Dickrell, Jeff (2001). Center of the Storm: The Bombing of Dutch Harbor and the Experience of Patrol Wing Four in the Aleutians, Summer 1942. Missoula, Montana: Pictorial Histories Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 1-57510-092-4. OCLC 50242148.

- Feinberg, Leonard (1992). Where the Williwaw Blows: The Aleutian Islands-World War II. Pilgrims' Process. ISBN 0-9710609-8-3. OCLC 57146667.

- Garfield, Brian (1995) [1969]. The Thousand-Mile War: World War II in Alaska and the Aleutians. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press. ISBN 0-912006-83-8. OCLC 33358488.

- Goldstein, Donald M.; Katherine V. Dillon (1992). The Williwaw War: The Arkansas National Guard in the Aleutians in World War. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-242-0. OCLC 24912734.

- Hays, Otis (2004). Alaska's Hidden Wars: Secret Campaigns on the North Pacific Rim. University of Alaska Press. ISBN 1-889963-64-X.

- Herder, Brian Lane (2019). The Aleutians 1942–43: Struggle for the North Pacific. Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. ISBN 9781472832542.

- Lorelli, John A. (1984). The Battle of the Komandorski Islands. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-093-9. OCLC 10824413.

- MacGarrigle, George L. Aleutian Islands. The U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2010.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (2001) [1951]. Aleutians, Gilberts and Marshalls, June 1942 – April 1944, vol. 7 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-316-58305-7. OCLC 7288530.

- Parshall, Jonathan; Tully, Anthony (2005). Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-923-0. OCLC 60373935.

- Perras, Galen Roger (2003). Stepping Stones to Nowhere, The Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and American Military Strategy, 1867 – 1945. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 1-59114-836-7. OCLC 53015264.

- Urwin, Gregory J. W. (2000). The Capture of Attu: A World War II Battle as Told by the Men Who Fought There. Bison Books. ISBN 0-8032-9557-X.

- Wetterhahn, Ralph (2004). The Last Flight of Bomber 31: Harrowing Tales of American and Japanese Pilots Who Fought World War II's Arctic Air Campaign. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-7867-1360-7.

External links

[edit]- Logistics Problems on Attu by Robert E. Burks.

- Aleutian Islands Chronology

- Aleutian Islands War

- Red White Black & Blue – feature documentary about The Battle of Attu in the Aleutians during World War II

- PBS Independent Lens presentation of Red White Black & Blue – The Making Of and other resources

- Soldiers of the 184th Infantry, 7th ID in the Pacific, 1943–1945

- US Army Infantry Combat pamphlet- Part Two: Attu

- Oral history interview with Robert Jeanfaivre, navy veteran who took part in the Battle of Attu [dead link] from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- Diary of Japanese doctor killed on Attu

- Battle of Attu - United Newsreel footage

- 1943 in Alaska

- 1943 in Japan

- Aleutian Islands campaign

- American Theater of World War II

- Battles of World War II involving Japan

- Battles of World War II involving the United States

- World War II operations and battles of the Pacific theatre

- Amphibious operations of World War II

- May 1943 events

- Amphibious operations involving the United States

- Attu Island