Gene Vincent

Gene Vincent | |

|---|---|

Vincent in 1957 | |

| Born | Vincent Eugene Craddock February 11, 1935 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | October 12, 1971 (aged 36) Newhall, California, U.S. |

| Occupations |

|

| Spouses | Ruth Ann Hand

(m. 1956; div. 1956)Darlene Hicks

(m. 1958; div. 1961)Margaret Russell

(m. 1963; div. 1965)Jackie Frisco (m. 1966) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1955–1971 |

| Labels | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1952–1955 |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | Korean War |

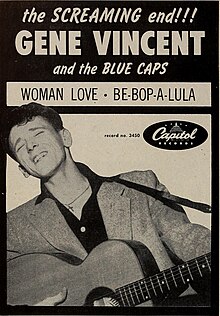

Vincent Eugene Craddock (February 11, 1935 – October 12, 1971), known as Gene Vincent, was an American rock and roll musician who pioneered the style of rockabilly. His 1956 top ten hit with his backing band the Blue Caps, "Be-Bop-a-Lula", is considered a significant early example of rockabilly.[2] His chart career was brief, especially in his home country of the US, where he notched three top 40 hits in 1956 and 1957, and never charted in the top 100 again. In the UK, he was a somewhat bigger star, racking up eight top 40 hits from 1956 to 1961.

Vincent was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and the Rockabilly Hall of Fame. He is sometimes referred to by his somewhat unusual nickname/moniker the "Screaming End".[3][4]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Craddock was born February 11, 1935, in Norfolk, Virginia,[5] to Mary Louise and Ezekiah Jackson Craddock.[6] His musical influences included country, rhythm and blues, and gospel. His favorite composition was Beethoven's Egmont overture. He showed his first real interest in music while his family lived in Munden Point (now Virginia Beach), in Princess Anne County, Virginia, near the North Carolina line, where they ran a country store. He received his first guitar at the age of twelve as a gift from a friend.

Craddock's father volunteered to serve in the U.S. Coast Guard and patrolled American coastal waters to protect Allied shipping against German U-boats during World War II. Craddock's mother maintained the general store in Munden Point. His parents moved the family to Norfolk, the home of a large naval base, and opened a general store and sailors' tailoring shop.

Craddock dropped out of school in 1952, at the age of seventeen, and enlisted in the United States Navy. As he was under the age of enlistment, his parents signed the forms allowing him to enter. He completed boot camp and joined the fleet as a crewman aboard the fleet oiler USS Chukawan, with a two-week training period in the repair ship USS Amphion, before returning to the Chukawan. He never saw combat but completed a Korean War deployment. He sailed home from Korean waters aboard the battleship USS Wisconsin but was not part of the ship's company.

Craddock planned a career in the Navy and, in 1955, used his $612 re-enlistment bonus to buy a new Triumph motorcycle. On July 4, 1955, while he was in Norfolk, his left leg was shattered in an auto crash.[7] He refused to allow the leg to be amputated, and the leg was saved, but the injury left him with a limp and pain. He wore a steel sheath as a leg brace[8] for the rest of his life. Most accounts relate the accident as the fault of a drunk driver who struck him. Years later in some of his music biographies, there is no mention of an accident, but it was claimed that his injury was due to a wound incurred in combat in Korea.[9] He spent time in the Portsmouth Naval Hospital and was medically discharged from the navy shortly thereafter.[5]

Early music career

[edit]Craddock became involved in the local music scene in Norfolk. He changed his name to Gene Vincent and formed a rockabilly band, Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps (a term used in reference to enlisted sailors in the U.S. Navy).[10] The band included Willie Williams on rhythm guitar (replaced in late 1956 by Paul Peek), Jack Neal on upright bass, Dickie Harrell on drums (died May 31, 2023, at age 82),[11] and Cliff Gallup on lead guitar.[5] He also collaborated with another rising musician, Jay Chevalier of Rapides Parish, Louisiana. Vincent and His Blue Caps soon gained a reputation playing in various country bars in Norfolk. There they won a talent contest organized by a local radio DJ, "Sheriff Tex" Davis, who then became Vincent's manager.[12]

Biggest hits

[edit]

In 1956 he wrote "Be-Bop-a-Lula", which drew comparisons to Elvis Presley[2] and which Rolling Stone magazine later listed as number 103 on its "500 Greatest Songs of All Time".[13] Local radio DJ "Sheriff Tex" Davis arranged for a demo of the song to be made, and this secured Vincent a contract with Capitol Records.[5] He signed a publishing contract with Bill Lowery of the Lowery Group of music publishers in Atlanta, Georgia. "Be-Bop-a-Lula" was not on Vincent's first album and was picked by Capitol producer Ken Nelson as the B-side of his first single, "Woman Love". Prior to the release of the single, Lowery pressed promotional copies of "Be-Bop-a-Lula" and sent them to radio stations throughout the country. By the time Capitol released the single, "Be-Bop-a-Lula" had already gained attention from the public and radio DJs. The song was picked up and played by other U.S. radio stations (obscuring the original A-side song) and became a hit, peaking at number 7 and spending 20 weeks on the Billboard pop chart[14] and reaching number 5 and spending 17 weeks on the Cash Box chart,[15] and launching Vincent's career as a rock-and-roll star.[16]

After "Be-Bop-a-Lula" became a hit, Vincent and His Blue Caps were unable to follow it up with the same level of commercial success, although they released critically acclaimed songs like "Race with the Devil" (number 96 on the Billboard chart and number 50 on the Cash Box chart) and "Bluejean Bop" (number 49 on the Billboard chart and another million-selling disc).[17]

Cliff Gallup left the band in 1956, and Russell Williford joined as the new guitarist for the Blue Caps. Williford played and toured Canada with Vincent in late 1956 but left the group in early 1957. Gallup came back to do the next album and then left again. Williford came back and exited again before Johnny Meeks joined the band.[18][19] The group had another hit in 1957 with "Lotta Lovin'" (highest position number 13 and spending 19 weeks on the Billboard chart and number 17 and 17 weeks on the Cashbox chart). Vincent was awarded gold records for two million sales of "Be-Bop-a-Lula",[17] and 1.5 million sales of "Lotta Lovin'".[citation needed] The same year he toured the east coast of Australia with Little Richard and Eddie Cochran, drawing audiences totaling 72,000 to their Sydney Stadium concerts. Vincent also made an appearance in the film The Girl Can't Help It, with Jayne Mansfield, performing "Be-Bop-a-Lula" with the Blue Caps in a rehearsal room.[5] "Dance to the Bop" was released by Capitol Records on October 28, 1957.[20] On November 17, 1957, Vincent and His Blue Caps performed the song on the nationally broadcast television program The Ed Sullivan Show.[21] The song spent nine weeks on the Billboard chart and peaked at number 23 on January 23, 1958 and reached number 36 and spent eight weeks on the Cashbox chart. It was Vincent's last American hit single.[22] The song was used in the movie Hot Rod Gang for a dance rehearsal scene featuring dancers doing the West Coast Swing.[20]

Vincent and His Blue Caps also appeared several times on Town Hall Party, California's largest country music barn dance, held at the Town Hall in Compton, California.[23] They appeared on October 25, 1958, and July 25 and November 7, 1959.[24] However, by the end of 1959 the Blue Caps were no longer part of the billing on Gene Vincent records. The late 1959 single "Wild Cat" was credited solely to Gene Vincent, and this would be the case on all subsequent Gene Vincent releases.

Europe

[edit]A dispute with the US tax authorities and the American Musicians' Union over payments to his band and his having sold the band's equipment to pay a tax bill led Vincent to leave the United States for Europe.[25]

On December 15, 1959, Vincent appeared on Jack Good's TV show, Boy Meets Girl, his first appearance in England. He wore black leather, gloves, and a medallion, and stood in a hunched posture.[5] Good is credited with the transformation of Vincent's image.[5] After the TV appearance he toured France, the Netherlands, Germany and the UK performing in his US stage clothes.[26]

On April 16, 1960, while on tour in the UK, Vincent, Eddie Cochran and the songwriter Sharon Sheeley were involved in a high-speed traffic accident in a private-hire taxi in Chippenham, Wiltshire. Vincent broke his ribs and collarbone and further damaged his weakened leg.[5] Sheeley suffered a broken pelvis. Cochran, who had been thrown from the vehicle, suffered serious brain injuries and died the next day. Vincent returned to the United States after the accident.[citation needed]

While they were preparing to board their taxi, Vincent and Cochran had rebuffed Tony Sheridan's request to ride along with them to the next venue. After escaping that fateful road accident,[27] Sheridan soon relocated to Hamburg, where he helped influence the musical training of many British groups who would later become part of the British Invasion, including one of his backing bands, the Beatles.

Promoter Don Arden had Vincent return to the UK in 1961 to do an extensive tour in theatres and ballrooms,[5] including the Agincourt Ballroom, Camberley[28] with Chris Wayne and the Echoes. In 1962 Vincent was on the same bill as the Beatles in Hamburg; Paul McCartney recalled an incident with a pistol at Vincent's girlfriend's hotel.[28] In 1963 Vincent appeared in court for pointing a gun at his then wife Margaret Russell and threatening to kill her, though his wife said in court that she had forgiven him.[29] After the overwhelming success of the UK tour, Vincent moved to Britain in 1963. On a UK tour Vincent had pulled a gun on Jet Harris, Harris hid behind John Leyton, the situation was defused and the three would later become friends.[30] His accompanying band, Sounds Incorporated, a six-piece outfit with three saxophones, guitar, bass and drums, went on to play with the Beatles at their Shea Stadium concert. Vincent toured the UK again in 1963 with the Outlaws, featuring future Deep Purple guitar player Ritchie Blackmore, as a backing band. Vincent's alcohol problems marred the tour, resulting in problems both on stage and with the band and management.[31]

Later career

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014) |

Vincent's attempts to re-establish his American career in folk rock and country rock proved unsuccessful; he is remembered today for recordings of the 1950s and early 1960s released by Capitol Records.[5] In the early 1960s, he also put out tracks on EMI's Columbia label, including a cover of Arthur Alexander's "Where Have You Been All My Life?" A backing band called the Shouts joined him.

In 1966 and 1967, in the United States, he recorded for Challenge Records, backed by ex-members of the Champs and Glen Campbell. Challenge released three singles in the US, and the UK London label released two singles and collected recordings on to an LP, Gene Vincent, on the UK London label in 1967. Although well received, none sold well. In 1968 in a hotel in Germany, Vincent tried to shoot Paul Raven, later to find fame as Gary Glitter. He fired several shots but missed and a frightened Raven left the country the next day.[32]

In 1969, he recorded the album I'm Back and I'm Proud for long-time fan John Peel's Dandelion Records,[5] produced by Kim Fowley with arrangements by Skip Battin (of the Byrds), Mars Bonfire on rhythm guitar, Johnny Meeks (of Blue Caps and Merle Haggard's The Strangers) on lead guitar, Jim Gordon on drums, and backing vocals by Linda Ronstadt and Jackie Frisco.[33] While recording the track "Sexy Ways" for the album Vincent threatened to get a gun from his car and shoot Paul A. Rothchild and John Densmore if they did not leave the studio; the pair then left the studio quickly.[34] He recorded two other albums for Kama Sutra Records, reissued on one CD by Rev-Ola in March 2008. On his 1969 tour of the UK he was backed by the Wild Angels, a British band that had performed at the Royal Albert Hall with Bill Haley & His Comets and Duane Eddy. Because of pressure from his ex-wife Margaret Russell, the Inland Revenue and promoter Don Arden, Vincent returned to the US.[35]

His final US recordings were four tracks for Rockin' Ronny Weiser's Rolling Rock label, a few weeks before his death. These were released on a compilation album of tribute songs, including "Say Mama", by his daughter, Melody Jean Vincent, accompanied by Johnny Meeks on guitar. On September 19, 1971, he began his last series of gigs in Britain.[36] He was backed by Richard Cole and Kansas Hook (Dave Bailey, Bob Moore, and bass player Charlie Harrison from Poco and Roger McGuinn's Thunderbyrd). They recorded four tracks ("Say Mama", "Be-Bop-A-Lula", "Roll Over Beethoven", "Distant Drums") at the BBC studios in Maida Vale, London, for Johnnie Walker's Radio 1 show. The fifth record ("Whole Lotta Shakin' Goin' On") remained unfinished.[37] He managed one show at the Garrick Night Club in Leigh, Lancashire, and two shows at the Wookey Hollow Club in Liverpool on October 3 and 4. Vincent then returned to the US and died a few days later. In September 1974, the BBC launched pop label BEEB with a maxi single by Vincent ("Roll Over Beethoven", BEEB 001). The single comprised three of these tracks.[38] The four tracks are now on Vincent's album White Lightning.[citation needed]

Death and legacy

[edit]Vincent died at the age of 36 on October 12, 1971, from a combination of a ruptured ulcer, internal hemorrhage and heart failure, while visiting his father in Saugus, California.[36][39][40] He is interred at Eternal Valley Memorial Park, in Newhall, California.

Vincent is mentioned in one of Ian Dury's earliest songs, "Upminster Kid"[41] (on the 1975 Kilburn and the High Roads album Handsome[42]), with the words "Well Gene Vincent Craddock remembered the love of an Upminster rock 'n' roll teen". Vincent had died just four years earlier.[41] He later recorded the song "Sweet Gene Vincent".

Vincent was the first inductee into the Rockabilly Hall of Fame upon its formation in 1997.[43] The following year he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[44] Vincent has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 1749 North Vine Street.[45][46] In 2012, his band, the Blue Caps, were retroactively inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame by a special committee, alongside Vincent.[47][48] On Tuesday, September 23, 2003, Vincent was honored with a Norfolk's Legends of Music Walk of Fame bronze star embedded in the Granby Street sidewalk.[49][50]

Writing for AllMusic, Ritchie Unterberger called Vincent "an American rockabilly legend who defined the greasy-haired, leather-jacketed, hot rods 'n' babes spark of rock and roll."[51] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau was less impressed by the musician's career, saying "Vincent was never a titan – his few moments of rockabilly greatness were hyped-up distillations of slavering lust from a sensitive little guy who was just as comfortable with 'Over the Rainbow' in his normal frame of mind." However, he included Vincent's compilation album The Bop That Just Won't Stop (1974) in his "basic record library", published in Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies (1981).[52]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

[edit]- Bluejean Bop! (Capitol T764. US & UK) (8/13/1956)

- Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps (Capitol T811, US & UK) (1957)

- Gene Vincent Rocks! And the Blue Caps Roll (Capitol T970, US & UK) (3/1958)

- A Gene Vincent Record Date (Capitol T1059, US & UK) (11/1958)

- Sounds Like Gene Vincent (Capitol T1207, US & UK) (6/1959)

- Crazy Times (Capitol T1342, US & UK mono) (Capitol ST1342, US & UK stereo) (3/1960)

- The Crazy Beat of Gene Vincent (Capitol T 20453, UK) (1963)

- Shakin' Up a Storm (Columbia 33-OSX 1646, UK) (1964)

- Gene Vincent (London HAH 8333, UK) (1967)

- I'm Back and I'm Proud (Dandelion D9 102, US) (1969) (Dandelion 63754, UK) (1970)

- Gene Vincent (Kama Sutra KSBS 2019, US) (1970) retitled If Only You Could See Me Today (Kama Sutra 2361009, UK) (1971)

- The Day the World Turned Blue (Kama Sutra KSBS 2027, US) (1970) (Kama Sutra 2316005, UK) (1971)

Compilations and bootlegs

[edit]- Rhythm in Blue (bootleg) (Bluecap Records BC2-11-35, Canada) (1979)

- Be-Bop-a-Lula (bootleg) (Koala KOA 14617, US) (1980)

- Forever Gene Vincent (Rolling Rock LP 022, US) (1980) (contains four rare recordings by Vincent)

- Dressed in Black (Magnum Force MFLP 016, UK) (1982)

- Gene Vincent with Interview by Red Robinson (bootleg) (Great Northwest Music Company GNW 4016, US) (1982)

- From LA to Frisco (Magnum Force MFLP 1023, UK) (1982)

- For Collectors Only (Magnum Force MFLP 020, UK) (1984)

- Rarities Vol 2 (bootleg) (Doktor Kollector DK 005, France) (1985)

- Rareties [sic] (bootleg) (Dr Kollector CRA 001, France) (1986)

- Important Words (Rockstar RSR LP 1020, UK) (1990)

- Lost Dallas Sessions (Rollercoaster RCCD 3031) (1998)

- Hey Mama! (Rollercoaster ROLL 2021, UK) (1998)

EPs

[edit]- Hot Rod Gang (Capitol EAP 1–985 US & UK) (9/58)

- Be-Bop-a-Lula '62 (Capitol EAP 1-20448 France) (62)

- Live and Rockin' (Fan club issue UK) (69)

- The Screamin' Kid Live! (bootleg) (no label 20240 France) (69)

- The Screaming Kid (bootleg) (no label 20.266 France) (69)

- Rainyday Sunshine (Rollin' Danny RD1 UK) (80)

- On Tour with Gene Vincent & Eddie Cochran (Rockstar RSR-EP 2013 UK) (86)

- In Concert Vol 1 (bootleg) (Savas SA 178305 France) (88)

- The Last Session (Strange Fruit SFNT 001 UK) (88)

- Hey Mama! (Rollercoaster RCEP 123 UK) (98)

- Blue Gene (Norton EP-076 US) (99)

(NB: This listing omits the many EPs of album tracks & compilations)

Singles

[edit]| Year | Titles (A-side, B-side) Both sides from same album except where indicated |

US single | UK single | Peak chart positions | US album | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US | UK | CAN | |||||

| 1956 | "Be-Bop-a-Lula" b/w "Woman Love" |

Capitol 3450 | Capitol 14599 | 7 | 16 | — | Gene Vincent's Greatest! |

| "Race with the Devil" b/w "Gonna Back Up Baby" (non-album track) |

Capitol 3530 | Capitol 14628 | 96 | 28 | — | ||

| "Blue Jean Bop" b/w "Who Slapped John" |

Capitol 3558 | Capitol 14637 | — | 16 | — | Bluejean Bop | |

| "Jumps, Giggles and Shouts" b/w "Wedding Bells" |

N/A | Capitol 14681 | — | — | — | ||

| 1957 | "Crazy Legs" b/w "Important Words" |

Capitol 3617 | Capitol 14693 | — | — | — | The Bop That Just Won't Stop (1956) (released 1974), and other lp's. |

| "B-I-Bickey-Bi, Bo-Bo-Go" b/w "Five Days" (non-album track) |

Capitol 3617 | Capitol 14693 | — | — | — | ||

| "Lotta Lovin'" b/w "Wear My Ring" (non-album track) |

Capitol 3763 | Capitol 14763 | 13 | — | 2 | Gene Vincent's Greatest! | |

| "Dance to the Bop" b/w "I Got It" |

Capitol 3839 | Capitol 14808 | 23 | — | 6 [53] | Non-album tracks | |

| 1958 | "I Got a Baby" b/w "Walkin' Home from School" |

Capitol 3874 | Capitol 14830 | — | — | — | |

| "Baby Blue" b/w "True to You" |

Capitol 3959 | Capitol 14868 | — | — | — | ||

| "Rocky Road Blues" b/w "Yes I Love You Baby" (from Gene Vincent's Greatest!) |

Capitol 4010 | Capitol 14908 | — | — | — | ||

| "Git It" b/w "Little Lover" (from Gene Vincent's Greatest!) |

Capitol 4051 | Capitol 14935 | — | — | — | A Gene Vincent Record Date | |

| "Say Mama" b/w "Be Bop Boogie Boy" |

Capitol 4105 | Capitol 14974 | — | — | — | Non-album tracks | |

| 1959 | "Over the Rainbow" b/w "Who's Pushing Your Swing" |

Capitol 4153 | Capitol 15000 | — | — | — | Gene Vincent's Greatest! |

| "Summertime" b/w "Frankie and Johnnie" (from Gene Vincent Rocks! And the Blue Caps Roll) |

N/A | Capitol 15035 | — | — | — | A Gene Vincent Record Date | |

| "The Night Is So Lonely" b/w "Right Now" |

Capitol 4237 | Capitol 15053 | — | — | — | Non-album tracks | |

| 1960 | "Wild Cat" b/w "Right Here on Earth" |

Capitol 4313 | Capitol 15099 | — | 21 | — | |

| "My Heart" b/w "I Got to Get You Yet" |

N/A | Capitol 15115 | — | 16 | — | Sounds Like Gene Vincent | |

| "Pistol Packin' Mama" US B-side: "Anna Annabelle" UK B-side: "Weeping Willow" |

Capitol 4442 | Capitol 15136 | — | 15 | — | Non-album tracks | |

| "Anna Annabelle" b/w "Accentuate the Positive" (from Crazy Times) |

N/A | Capitol 15169 | — | — | — | ||

| 1961 | "Jezebel" b/w "Maybe" (from Sounds Like Gene Vincent) |

N/A | Capitol 15179 | — | — | — | Bluejean Bop |

| "If You Want My Lovin'" b/w "Mister Loneliness" |

Capitol 4525 | Capitol 15185 | — | — | — | Non-album tracks | |

| "She She Little Sheila" b/w "Hot Dollar" |

N/A | Capitol 15202 | — | 22 | — | Crazy Times | |

| "I'm Going Home" b/w "Love of a Man" |

N/A | Capitol 15215 | — | 36 | — | Non-album tracks | |

| "Brand New Beat" b/w "Unchained Melody" (from Gene Vincent and the Blue Caps) |

N/A | Capitol 15231 | — | — | — | Gene Vincent Rocks! And the Blue Caps Roll | |

| "Lucky Star" b/w "Baby Don't Believe Him" |

Capitol 4665 | Capitol 15243 | — | — | — | Non-album tracks | |

| 1962 | "Be-Bop-a-Lula '62" b/w "King of Fools" |

N/A | Capitol 15264 | — | — | — | |

| 1963 | "Held for Questioning" b/w "You're Still in My Heart" |

N/A | Capitol 15290 | — | — | — | |

| "Crazy Beat" b/w "High Blood Pressure" |

N/A | Capitol 15307 | — | — | — | ||

| "Where Have You Been All My Life" b/w "Temptation Baby" |

N/A | Columbia 7174 | — | — | — | ||

| 1964 | "Humpity Dumpity" b/w "A Love 'Em and Leave 'Em Kinda Guy" |

N/A | Columbia 7218 | — | — | — | |

| "La Den Da Den Da Da" b/w "The Beginning of the End" |

N/A | Columbia 7293 | — | — | — | ||

| "Private Detective" b/w "You Are My Sunshine" |

N/A | Columbia 7343 | — | — | — | ||

| 1966 | "Bird Doggin'" b/w "Ain't That Too Much" |

Challenge 59337 | London 10079 | — | — | — | |

| "Lonely Street" b/w "I've Got My Eyes on You" |

Challenge 59347 | London 10099 | — | — | — | ||

| 1967 | "Born to Be a Rolling Stone" b/w "Hurtin' for You Baby" |

Challenge 59365 | N/A | — | — | — | |

| 1969 | "Be-Bop-a-Lula '69" b/w "Ruby Baby" |

N/A | Dandelion 4596 | — | — | — | I'm Back and I'm Proud |

| "Story of the Rockers" b/w "Pickin' Poppies" |

Playground 100 Forever 6001 |

Spark 1091 | — | — | — | Non-album tracks | |

| 1970 | "White Lightning" b/w "Scarlet Ribbons" |

N/A | Dandelion 4974 | — | — | — | I'm Back and I'm Proud |

| "Sunshine" b/w "Geese" |

Kama Sutra 514 | N/A | — | — | — | Gene Vincent | |

| "The Day the World Turned Blue" US B-side: "How I Love Them Old Songs" UK B-side: "High on Life" |

Kama Sutra 518 | Kama Sutra 2013 018 | — | — | — | The Day the World Turned Blue | |

Film appearances

[edit]- The Girl Can't Help It (1956)

- Hot Rod Gang (1958, a.k.a. Fury Unleashed)

- It's Trad, Dad! (1962, a.k.a. Ring a Ding Rhythm)

- Live It Up! (1963, a.k.a. Sing and Swing)

- The Rock And Roll Singer (1970) - documentary of Vincent's London tour of 1969[54]

Vincent was played by Carl Barât in the 2009 film Telstar

Bibliography

[edit]- Britt Hagarty: The Day The World Turned Blue Blandford Press (1984) ISBN 0-7137-1531-6

- Susan Vanhecke: Race With the Devil: Gene Vincent's Life in the Fast Lane. Saint Martin's Press (2000) ISBN 0-312-26222-1

- Steven Mandich: Sweet Gene Vincent (The Bitter End) Orange Syringe Publications. (2002) 1000 Printed. ISBN 0-9537626-0-2

- Mick Farren: Gene Vincent. There's One In Every Town The Do-Not Press (2004) ISBN 1-904316-37-9

- John Collis: Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran, Rock 'N' Roll Revolutionaries Virgin Books (2004) ISBN 1-85227-193-0

- Derek Henderson: Gene Vincent, A Companion Spent Brothers Productions (2005) ISBN 0-9519416-7-4 (NB contains an extensive Bibliography on Gene Vincent)

References

[edit]- ^ "Gene Vincent - Universal Music France". February 7, 2021. Archived from the original on February 7, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 8 – The All American Boy: Enter Elvis and the Rock-a-Billies. [Part 2]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Track 3.

- ^ "Gene Vincent: The hero before The Beatles". faroutmagazine.co.uk. October 12, 2021. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Chaddock, Ian. "GENE VINCENT". Vivelerock.net. Archived from the original on December 28, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Colin Larkin, ed. (1997). The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music (Concise ed.). Virgin Books. p. 1218. ISBN 1-85227-745-9.

- ^ "Gene Vincent Biography". Musicianguide.com. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Henderson, Derek (2005). Gene Vincent: a companion. Southampton: Spent Brothers Productions. p. 3. ISBN 0-9519416-7-4. OCLC 70671058.

- ^ Perrin, Jean-Éric [in French]; Rey, Jerôme; Verlant, Gilles (2009). Les Miscellanées du rock. Paris: Éditions Fetjaine / La Martinière. p. 252. ISBN 978-2-35425-130-7.

Gene choisit de se faire poser une gaine d'acier autour des restes de son membre

- ^ Tobler, John (1992). NME Rock 'n' Roll Years. London: Reed International Books. p. 231. CN 5585.

- ^ "Official Gene Vincent website". Rockabillyhall.com. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "Richard Dickie Be-Bop Harrell Sr". lovingfuneralhome.com. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Sheriff Tex Davis". The Independent. London, UK. September 13, 2007. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ "The RS 500 Greatest Songs of All Time". Rolling Stone. December 9, 2004. Archived from the original on June 22, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ Henderson 2005, p. 152.

- ^ "Cash Box Country Singles 11/03/56". CASHBOX Magazine. Archived from the original on March 11, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Bronson, Fred (1995). Billboard's hottest hot 100 hits. New York: Billboard Books. p. 253. ISBN 0-8230-7646-6. OCLC 32014167.

- ^ a b Murrells, Joseph (1978). The Book of Golden Discs (2nd ed.). London: Barrie and Jenkins. p. 87. ISBN 0-214-20512-6.

- ^ Dregni, Michael (April 22, 2019). "Cliff Gallup". Vintage Guitar® magazine. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Carey, Kevin (February 1, 2009). "Russell Williford. The Best Known, Unknown Blue Cap". Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ a b "Vincent, Gene". RCS Discography. Archived March 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Ed Sullivan Show, Season 10, Episode 8, November 17, 1957: Gene Vincent & the Blue Caps, Georgia Gibbs, Carol Burnett, Johnny Carson". TV.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "HOT ROD GANG DVD Movie – 1958 Movie on DVD! – Gene Vincent Movie Hot Rods – Hot Rod Gang". Thevideobeat.com. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Hillbilly-Music.com. "Town Hall Party". hillbilly-music.com. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ "Gene Vincent – At Town Hall Party Production Details". Yahoo! Movies. Retrieved April 29, 2012.

- ^ Farren, Mick (2010). "Gene Vincent – The Genesis of the Dark Side". In Driver, Jim. (ed.). The Mammoth Book of Sex, Drugs & Rock 'n' Roll. London: Constable & Robinson. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-1-84901-461-8. OCLC 784882138.

- ^ Farren, Mike (2004). Gene Vincent There's One in Every Town. Do Not Press. pp. 75–80. ISBN 1-904316-37-9.

- ^ https://www.rte.ie/radio/doconone/771586-are-you-tony-sheridan Martin Duffy. Are You Tony Sheridan? (RTÉ Doc on One radio documentary), 17 July 2010.

- ^ a b Ronnie Wood (Show) in conversation with Paul McCartney confirmed meeting Vincent at the venue. sky.com/ronnie

- ^ "Gene Vincent | Singer who pointed gun at wife says 'She forgives me'". Spentbrothers.com. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Cochran, Bobby (2003). "U. K. Tour". Three Steps to Heaven: The Eddie Cochran Story. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-634-03252-3.

- ^ Bloom, Jerry (2008). Black Knight. Omnibus Press.

- ^ "Regrettable Television: This Is Your Life, Gary Glitter". Channelhopping.onthebox.com. December 14, 2012. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ Henderson 2005, p. 34.

- ^ "Gene Vincent | I'm Back and I'm Proud". Spentbrothers.com. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Hagarty, Britt (1984). The day the world turned blue: a biography of Gene Vincent. Poole: Blandford. p. 245. ISBN 0-7137-1531-6. OCLC 11869138.

- ^ a b Henderson 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Henderson 2005, p. 36.

- ^ "BBC's BEEB to Bow With Maxi-Single". Billboard. September 14, 1974. p. 56.

- ^ The Harmony illustrated encyclopedia of rock. Clifford, Mike., Frame, Pete, 1942-, Tobler, John., Hanel, Ed., St. Pierre, Roger., Trengove, Chris. (5th ed.). New York: Harmony Books. 1986. p. 221. ISBN 0-517-56264-2. OCLC 13860782.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Farren, Mick. (2004). Gene Vincent : there's one in every town. London: Do-Not Press. p. 138. ISBN 1-904316-37-9. OCLC 56452920.

- ^ a b Starkey, Arun (October 12, 2022). "Exploring the influence of Gene Vincent on Ian Dury". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (December 31, 1969). "Kilburn & the High Roads - Handsome Album Reviews, Songs & More". AllMusic. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ "Rockabilly Hall of Fame Inductess". Rockabillyhall.com. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ McDonald, Sam (January 11, 1998). "Gene Vincent: Early Rocker's Legacy Bops Into Hall of Fame". Daily Press (published January 11, 1998). Archived from the original on February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Gene Vincent". Hollywood Walk of Fame. October 25, 2019. Retrieved February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Gene Vincent - Hollywood Star Walk". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 11, 2021.

- ^ "Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Adds Six Backing Groups to the Class of 2012". Rolling Stone. February 9, 2012. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021.

- ^ "Rock Hall Inducting Bands of 6 Iconic Members Billboard". Billboard. February 9, 2012. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021.

- ^ McDonald, Sam (September 9, 2003). "Region's Legends to be Honored". Daily Press. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021.

- ^ "Legends of Music Walk of Fame". Downtown Norfolk. Archived from the original on February 13, 2021.

- ^ Unterberger, Ritchie (n.d.). "Gene Vincent". AllMusic. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: V". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 089919026X. Retrieved March 21, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ "CHUM Hit Parade - January 6, 1958".

- ^ "BBC Arts - BBC Arts, The Rock and Roll Singer". BBC. March 24, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2023.

External links

[edit]- Official Gene Vincent website Archived February 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine from Rockabilly Hall of Fame.

- "Gene Vincent". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

- Official fan club Gene Vincent Lonely Street

- Derek Henderson's Gene Vincent website

- Findagrave: Gene Vincent

- Gene Vincent at IMDb

- Gene Vincent discography at Discogs

- 1935 births

- 1971 deaths

- 20th-century American singer-songwriters

- American bandleaders

- American male singer-songwriters

- American male guitarists

- American country rock singers

- American rock singers

- American country guitarists

- American rock guitarists

- American rockabilly guitarists

- American rockabilly musicians

- Guitarists from Virginia

- American expatriates in the United Kingdom

- American musicians with disabilities

- American rock musicians

- Apex Records artists

- Capitol Records artists

- Challenge Records artists

- Dandelion Records artists

- Kama Sutra Records artists

- Norton Records artists

- Singer-songwriters from Virginia

- Musicians from Norfolk, Virginia

- Rock and roll musicians

- United States Navy personnel of the Korean War

- United States Navy sailors

- American people of Welsh descent

- Deaths from ulcers

- 20th-century American guitarists

- 20th-century American male singers

- Deaths from bleeding