Land transport

Land transport is the transport or movement of people, animals or goods from one location to another location on land. This is in contrast with other main types of transport such as maritime transport and aviation. The two main forms of land transport can be considered to be rail transport and road transport.

Systems

[edit]Several systems of land transport have been devised, from the most basic system of humans carrying things from place to sophisticated networks of ground-based transportation using different types of vehicles and infrastructure. The three types are human-powered, animal powered and machine powered

Human-powered transportation

[edit]

Human-powered transport, a form of sustainable transportation, is the transport of people and/or goods using human muscle-power, in the form of walking, running and swimming. Modern technology has allowed machines to enhance human power. Human-powered transport remains popular for reasons of cost-saving, leisure, physical exercise, and environmentalism; it is sometimes the only type available, especially in underdeveloped or inaccessible regions.

Although humans are able to walk without infrastructure, the transport can be enhanced through the use of roads, especially when using the human power with vehicles, such as bicycles and inline skates. Human-powered vehicles have also been developed for difficult environments, such as snow and water, by watercraft rowing and skiing; even the air can be entered with human-powered aircraft.

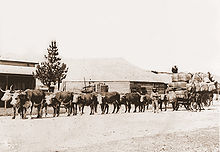

Animal-powered transportation

[edit]Animal-powered transport is the use of working animals for the movement of people and goods. Humans may ride some of the animals directly, use them as pack animals for carrying goods, or harness them, alone or in teams, to pull sleds or wheeled vehicles.

Road transportation

[edit]

A road is an identifiable route, way or path between two or more places.[1] Roads are typically smoothed, paved, or otherwise prepared to allow easy travel;[2] though they need not be, and historically many roads were simply recognizable routes without any formal construction or maintenance.[3] In urban areas, roads may pass through a city or village and be named as streets, serving a dual function as urban space easement and route.[4]

The most common road vehicle is the automobile; a wheeled passenger vehicle that carries its own motor. Other users of roads include buses, trucks, motorcycles, bicycles and pedestrians. As of 2002, there were 590 million automobiles worldwide. Road transport offers a complete freedom to road users to transfer the vehicle from one lane to the other and from one road to another according to the need and convenience. This flexibility of changes in location, direction, speed, and timings of travel is not available to other modes of transport. It is possible to provide door to door service only by road transport.

Automobiles offer high flexibility and with low capacity, but are deemed with high energy and area use, and the main source of noise and air pollution in cities; buses allow for more efficient travel at the cost of reduced flexibility.[5] Road transport by truck is often the initial and final stage of freight transport.

Rail transportation

[edit]

Rail transport is where a train runs along a set of two parallel steel rails, known as a railway or railroad. The rails are anchored perpendicular to ties (or sleepers) of timber, concrete or steel, to maintain a consistent distance apart, or gauge. The rails and perpendicular beams are placed on a foundation made of concrete or compressed earth and gravel in a bed of ballast. Alternative methods include monorail and maglev.

A train consists of one or more connected vehicles that run on the rails. Propulsion is commonly provided by a locomotive, that hauls a series of unpowered cars, that can carry passengers or freight. The locomotive can be powered by steam, diesel or by electricity supplied by trackside systems. Alternatively, some or all the cars can be powered, known as a multiple unit. Also, a train can be powered by horses, cables, gravity, pneumatics and gas turbines. Railed vehicles move with much less friction than rubber tires on paved roads, making trains more energy efficient, though not as efficient as ships.

Intercity trains are long-haul services connecting cities;[6] modern high-speed rail is capable of speeds up to 350 km/h (220 mph), but this requires specially built track. Regional and commuter trains feed cities from suburbs and surrounding areas, while intra-urban transport is performed by high-capacity tramways and rapid transits, often making up the backbone of a city's public transport. Freight trains traditionally used box cars, requiring manual loading and unloading of the cargo. Since the 1960s, container trains have become the dominant solution for general freight, while large quantities of bulk are transported by dedicated trains.

Other modes

[edit]

Pipeline transport sends goods through a pipe; most commonly liquid and gases are sent, but pneumatic tubes can also send solid capsules using compressed air. For liquids/gases, any chemically stable liquid or gas can be sent through a pipeline. Short-distance systems exist for sewage, slurry, water, and beer, while long-distance networks are used for petroleum and natural gas.

Cable transport is a broad mode where vehicles are pulled by cables instead of an internal power source. It is most often used on steep slopes. Typical solutions include aerial tramways, elevators, escalator and ski lifts; some of these are also categorized as conveyor transport.

Connections with other modes

[edit]Airports

[edit]Airports serve as a station for air transport activities, but most people and cargo transported by air must use ground transport to reach their final destination. Airport-based services are sometimes used to shuttle people to nearby hotels or motels when overnight stay is required for connecting flights. Companies provide rental cars, private bus and taxi services while mass transportation is usually provided by a municipality or other source of public funding. Several major airports, including Denver International and JFK International, provide many types of ground transportation, often by working with livery companies and similar businesses. Smaller airports may only have a few private rental companies and a bus service. Larger airports tend to offer several different transportation options, such as light rail and/or roads that loop around an airport to provide access from multiple terminals.

Seaports

[edit]As with air transport, sea transport typically requires use of ground transport at either end of travel for people or goods to reach their final destinations. Significant infrastructure is used at ports to transfer people and goods between sea and land systems.

Elements

[edit]Infrastructure

[edit]

Infrastructure is the fixed installations that allow a vehicle to operate. It consists of a way, a terminal, and facilities for parking and maintenance. For rail, pipeline, road, and cable transport, the entire way the vehicle travels must be built up.

Terminals such as stations are locations where passengers and freight can be transferred from one vehicle or mode to another. For passenger transportation, terminals integrate different modes to allow riders to interchange to take advantage of each mode's advantages. For instance, airport rail links connect airports to the city centers and suburbs. The terminals for automobiles are parking lots, while buses and coaches can operate from simple stops.[7] For freight, terminals act as transshipment points, though some cargo is transported directly from the point of production to the point of use.

The financing of infrastructure can either be public or private. Transportation is often a natural monopoly and a necessity for the public; roads, and in some countries railways and airports are funded through taxation. New infrastructure projects can have high cost and are often financed through debt. Many infrastructure owners then impose usage fees, such as landing fees at airports, or toll plazas on roads. Independent of this, authorities may impose taxes on the purchase or use of vehicles. Because of poor forecasting and overestimation of passenger numbers by planners, there is frequently a benefit shortfall for transport infrastructure projects.[8]

Vehicles

[edit]

A vehicle is any non-living device that is used to move people and goods. Unlike the infrastructure, the vehicle moves along with the cargo and riders. Unless being pulled by a cable or muscle-power, the vehicle must provide its own propulsion; this is most commonly done through a steam engine, combustion engine, or electric motor, though other means of propulsion also exist. Vehicles also need a system of converting the energy into movement; this is most commonly done through wheels, propellers and pressure.

Vehicles are most commonly staffed by a driver. However, some systems, such as people movers and some rapid transits, are fully automated. For passenger transport, the vehicle must have a compartment for the passengers. Simple vehicles, such as automobiles, bicycles or simple aircraft, may have one of the passengers as a driver.

Users

[edit]Public

[edit]Public land transport refers to the carriage of people and goods by government or commercial entities which is made available to the public at large for the purpose of facilitating the economy and society they serve. Most transport infrastructure and large transport vehicles are operated in this manner. Funds to pay for such transport may come from taxes, subscriptions, direct user fees, or combinations of these methods. The vast majority of public transport is land-based, with commuting and postal delivery being the primary purposes.

Commerce

[edit]Commercial land transport refers to the carriage of people and goods by commercial entities made available at cost to individuals, businesses, and the government for the purpose of profiting the entities providing the travel. Most infrastructure used is publicly owned, and vehicles tend to be large and efficient to maximize capacity and profit margins. Freight shipping and long-distance travel are common uses served by commercial land transport.

Military

[edit]Military land transport refers to the carriage of people and goods by the military or other operators for the purpose of supporting military operations, both in peacetime as well as in combat areas. Such activity may use a combination of public infrastructure as well as military-specific infrastructure and in many cases is designed to operate with little or no infrastructure when necessary. Vehicles can range from basic commercial or even private vehicles to those specifically designed for military use.

Private

[edit]Private land transport refers to individuals and organizations transporting themselves and their own people, animals, and goods at their own discretion. Vehicles used are typically smaller, though publicly owned infrastructure is often used for travel.

Function

[edit]Relocation of travelers and cargo are the most common uses of transport. However, other uses exist, such as the strategic and tactical relocation of armed forces during warfare, or the civilian mobility construction or emergency equipment.

Passenger

[edit]

Passenger transport, or travel, is divided into public and private transport. Public transport is scheduled services on fixed routes, while private is vehicles that provide ad hoc services at the riders desire. The latter offers better flexibility, but has lower capacity, and a higher environmental impact. Travel may be as part of daily commuting, for business, leisure or migration.

Short-haul transport is dominated by the automobile and mass transit. The latter consists of buses in rural and small cities, supplemented with commuter rail, trams and rapid transit in larger cities. Long-haul transport involves the use of the automobile, trains, coaches and aircraft, the last of which have become predominantly used for the longest, including intercontinental, travel. Intermodal passenger transport is where a journey is performed through the use of several modes of transport; since all human transport normally starts and ends with walking, all passenger transport can be considered intermodal. Public transport may also involve the intermediate change of vehicle, within or across modes, at a transport hub, such as a bus or railway station.

Taxis and buses can be found on both ends of the public transport spectrum. Buses are the cheaper mode of transport but are not necessarily flexible, and taxis are very flexible but more expensive. In the middle is demand-responsive transport, offering flexibility whilst remaining affordable.

International travel may be restricted for some individuals due to legislation and visa requirements.

Freight

[edit]Freight transport, or shipping, is a key in the value chain in manufacturing.[9] With increased specialization and globalization, production is being located further away from consumption, rapidly increasing the demand for transport.[10] While all modes of transport are used for cargo transport, there is high differentiation between the nature of the cargo transport, in which mode is chosen.[11] Logistics refers to the entire process of transferring products from producer to consumer, including storage, transport, transshipment, warehousing, material-handling and packaging, with associated exchange of information.[12] Incoterm deals with the handling of payment and responsibility of risk during transport.[13]

Containerization, with the standardization of ISO containers on all vehicles and at all ports, has revolutionized international and domestic trade, offering huge reduction in transshipment costs. Traditionally, all cargo had to be manually loaded and unloaded into the haul of any car; containerization allows for automated handling and transfer between modes, and the standardized sizes allow for gains in economy of scale in vehicle operation. This has been one of the key driving factors in international trade and globalization since the 1950s.[14]

Bulk transport is common with cargo that can be handled roughly without deterioration; typical examples are ore, coal, cereals and petroleum. Because of the uniformity of the product, mechanical handling can allow enormous quantities to be handled quickly and efficiently. The low value of the cargo combined with high volume also means that economies of scale become essential in transport, and whole trains are commonly used to transport bulk. Liquid products with sufficient volume may also be transported by pipeline.

History

[edit]

Humans' first means of land transport was walking. The domestication of animals introduces a new way to lay the burden of transport on more powerful creatures, allowing heavier loads to be hauled, or humans to ride the animals for higher speed and duration. Inventions such as the wheel and sled helped make animal transport more efficient through the introduction of vehicles. However, water transport, including rowed and sailed vessels, was the only efficient way to transport large quantities or over large distances prior to the Industrial Revolution.

The first forms of road transport were horses, oxen or even humans carrying goods over dirt tracks that often followed game trails. Paved roads were built by many early civilizations, including Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley civilization. The Persian and Roman empires built stone-paved roads to allow armies to travel quickly. Deep roadbeds of crushed stone underneath ensured that the roads kept dry. The medieval Caliphate later built tar-paved roads. Until the Industrial Revolution, transport remained slow and costly, and production and consumption were located as close to each other as feasible.

The Industrial Revolution in the 19th century saw a number of inventions fundamentally change transport. With telegraphy, communication became instant and independent of transport. The invention of the steam engine, closely followed by its application in rail transport, made land transport independent of human or animal muscles. Both speed and capacity increased rapidly, allowing specialization through manufacturing being located independent of natural resources.

With the development of the combustion engine and the automobile at the turn into the 20th century, road transport became more viable, allowing the introduction of mechanical private transport. The first highways were constructed during the 19th century with macadam. Later, tarmac and concrete became the dominant paving material.

After World War II, the automobile and airlines took higher shares of transport, reducing rail to freight and short-haul passenger.[15] In the 1950s, the introduction of containerization gave massive efficiency gains in freight transport, permitting globalization.[14] International air travel became much more accessible in the 1960s, with the commercialization of the jet engine. Along with the growth in automobiles and motorways, this introduced a decline for rail transport. After the introduction of the Shinkansen in 1964, high-speed rail in Asia and Europe started taking passengers on long-haul routes from airlines.[15]

Early in U.S. history, most aqueducts, bridges, canals, railroads, roads, and tunnels were owned by private joint-stock corporations. Most such transportation infrastructure came under government control in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, culminating in the nationalization of inter-city passenger rail service with the creation of Amtrak. Recently, however, a movement to privatize roads and other infrastructure has gained some ground and adherents.[16]

Impact

[edit]Economic

[edit]

Transport is a key necessity for specialization—allowing production and consumption of products to occur at different locations. Transport has throughout history been a spur to expansion; better transport allows more trade and a greater spread of people. Economic growth has always been dependent on increasing the capacity and rationality of transport.[17] But the infrastructure and operation of transport has a great impact on the land and is the largest drainer of energy, making transport sustainability a major issue.

Modern society dictates a physical distinction between home and work, forcing people to transport themselves to places of work or study, as well as to temporarily relocate for other daily activities. Passenger transport is also the essence of tourism, a major part of recreational transport. Commerce requires the transport of people to conduct business, either to allow face-to-face communication for important decisions or to move specialists from their regular place of work to sites where they are needed.

Planning

[edit]Transport planning allows for high utilization and less impact regarding new infrastructure. Using models of transport forecasting, planners are able to predict future transport patterns. On the operative level, logistics allows owners of cargo to plan transport as part of the supply chain. Transport as a field is studied through transport economics, the backbone for the creation of regulation policy by authorities. Transport engineering, a sub-discipline of civil engineering, must take into account trip generation, trip distribution, mode choice and route assignment, while the operative level is handled through traffic engineering.

Because of the negative impacts made, transport often becomes the subject of controversy related to choice of mode, as well as increased capacity. Automotive transport can be seen as a tragedy of the commons, where the flexibility and comfort for the individual deteriorate the natural and urban environment for all. Density of development depends on mode of transport, with public transport allowing for better spatial utilization. Good land use keeps common activities close to people's homes and places higher-density development closer to transport lines and hubs, to minimize the need for transport. There are economies of agglomeration. Beyond transportation some land uses are more efficient when clustered. Transportation facilities consume land, and in cities, pavement (devoted to streets and parking) can easily exceed 20 percent of the total land use. An efficient transport system can reduce land waste.

Too much infrastructure and too much smoothing for maximum vehicle throughput means that in many cities there is too much traffic and many—if not all—of the negative impacts that come with it. It is only in recent years that traditional practices have started to be questioned in many places, and as a result of new types of analysis which bring in a much broader range of skills than those traditionally relied on—spanning such areas as environmental impact analysis, public health, sociologists as well as economists—the viability of the old mobility solutions is increasingly being questioned. European cities are leading this transition.

Environment

[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

Transport is a major use of energy and burns most of the world's petroleum. This creates air pollution, including nitrous oxides and particulates, and is a significant contributor to global warming through emission of carbon dioxide,[18] for which transport is the fastest-growing emission sector.[19] By subsector, road transport is the largest contributor to global warming.[18] Environmental regulations in developed countries have reduced individual vehicles' emissions; however, this has been offset by increases in the numbers of vehicles and in the use of each vehicle.[18] Some pathways to reduce the carbon emissions of road vehicles considerably have been studied.[20][21] Energy use and emissions vary largely between modes, causing environmentalists to call for a transition from road to rail and human-powered transport, as well as increased transport electrification and energy efficiency.

Other environmental impacts of transport systems include traffic congestion and automobile-oriented urban sprawl, which can consume natural habitat and agricultural lands. By reducing transportation emissions globally, it is predicted that there will be significant positive effects on Earth's air quality, acid rain, smog and climate change.[22]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Major Roads of the United States". United States Department of the Interior. 2006-03-13. Archived from the original on 13 April 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ "Road Infrastructure Strategic Framework for South Africa". National Department of Transport (South Africa). Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ Lay, 1992: 6–7[full citation needed]

- ^ "What is the difference between a road and a street?". Word FAQ. Lexico Publishing Group. 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2007.

- ^ Cooper et al., 1998: 278[full citation needed]

- ^ Cooper et al., 1998: 279[full citation needed]

- ^ Cooper et al., 1998: 275–76[full citation needed]

- ^ Flyvbjerg, Bent; Skamris Holm, Mette K.; Buhl, Søren L. (30 June 2005). "How (In)accurate Are Demand Forecasts in Public Works Projects?: The Case of Transportation". Journal of the American Planning Association. 71 (2): 131–146. arXiv:1303.6654. doi:10.1080/01944360508976688. S2CID 154699038.

- ^ Chopra & Meindl 2007, p. 3.

- ^ Chopra & Meindl 2007, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Chopra & Meindl 2007, p. 54.

- ^ Bardi, Coyle & Novack 2006, p. 4.

- ^ Bardi, Coyle & Novack 2006, p. 473.

- ^ a b Bardi, Coyle & Novack 2006, pp. 211–214.

- ^ a b Cooper et al., 1998: 277[full citation needed]

- ^ Clifford Winston, Last Exit: Privatization and Deregulation of the U.S. Transportation System (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 2010).

- ^ Stopford, Martin (1997). "The economic role of the shipping industry". Maritime Economics. Psychology Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-415-15310-2.

- ^ a b c Fuglestvedt, Jan; Berntsen, Terje; Myhre, Gunnar; Rypdal, Kristin; Skeie, Ragnhild Bieltvedt (15 January 2008). "Climate forcing from the transport sectors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (2): 454–458. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105..454F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702958104. PMC 2206557. PMID 18180450.

- ^ Worldwatch Institute (16 January 2008). "Analysis: Nano Hypocrisy?". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ "Claverton-Energy.com". Claverton-Energy.com. 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Data on the barriers and motivators to more sustainable transport behaviour is available in the UK Department for Transport study "Climate Change and Transport Choices Archived 2011-05-30 at the Wayback Machine" published in December 2010.

- ^ Environment Canada. "Transportation". Archived from the original on July 13, 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2008.

Works

[edit]- Bardi, Edward J.; Coyle, John Joseph; Novack, Robert A. (2006). Management of Transportation. Thomson/South-Western. ISBN 978-0-324-31443-4.

- Chopra, Sunil; Meindl, Peter (2007). Supply Chain Management: Strategy, Planning, and Operation. Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-173042-7.