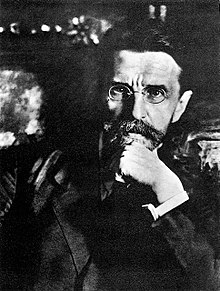

Vatslav Vorovsky

Vatslav Vatslavovich Vorovsky | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 27 October 1871 |

| Died | 10 May 1923 (aged 51) |

| Resting place | Kremlin Wall Necropolis, Moscow |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Other names | P. Orlovsky, Y. Adamovich, M. Schwarz, Josephine, Felix Alexandrovich |

| Occupation(s) | Diplomat, journalist, literary critic |

| Years active | 1895–1923 |

| Known for | being the victim of a political assassination |

Vatslav Vatslavovich Vorovsky (Russian: Ва́цлав Ва́цлавович Воро́вский; 27 October [O.S. 15 October] 1871 – 10 May 1923) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, literary critic, journalist, and Soviet diplomat. One of the first Soviet diplomats, Vorovsky is best remembered as the victim of a May 1923 political assassination in Switzerland, where he was the official representative of the Soviet government to the Conference of Lausanne.

Biography

[edit]Early years

[edit]Vatslav Vorovsky was born on 27 October 1871 (n.s.) in Moscow, the son of an ethnically Polish but Russified noble and engineer.[1] His father died when he was a year old, and he was raised by his mother. Following the completion of secondary school. In 1890, Vorovsky enrolled at the University of Moscow, where he was exposed to the ideas of political radicalism.[1]

Political career

[edit]In his autobiography, Vorovsky dated his involvement with the socialist movement from 1894, when he made contact with workers' circles in Moscow.[2] He was arrested by the Tsarist secret police in 1897, held for two years in Taganka Prison, then exiled in 1899 to the city of Orlov.[1] Upon his release, Vorovsky adopted a new underground pseudonym, "P. Orlovsky", as a tribute to this experience.[1] During the course of his underground career, Vorovsky also used the pseudonyms "Y. Adamovich", "M. Schwarz", "Josephine", and "Felix Alexandrovich".[1]

Vorovsky emigrated to Europe in 1902, spending time in Italy, Germany, and Switzerland.[1] He acted as an agent for the newspaper Iskra, founded abroad by Vladimir Lenin. In 1903 he was a founding member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party. During 1904, he was based in Odesa, Ukraine, but emigrated again in August 1904,[3] to help launch the first exclusively Bolshevik publication, Vperyod (Forward), of which he was an editor.[1]

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, Vorovsky returned to Russia, working actively as a revolutionary in St. Petersburg.[1] Following the defeat of the 1905 uprising he moved to Odesa, where he was a leading underground Bolshevik from 1907 to 1912.[1] In 1912, Vorovsky was arrested again, this time to be deported to Vologda province, in Russia.[2] In 1915, he moved to Stockholm, where he worked as an engineer for the Swedish Lux company and for Siemens-Schuckert. [4] In 1917, after the February Revolution in Russia, Vorovsky was appointed to three-man Bolshevik Stockholm Bureau, along with Karl Radek and Yakov Hanecki.

Vorovsky was the first director of Gosizdat, the State Publishing House, from its foundation in 1919 until 1921.[5]

Diplomatic career

[edit]Following the victory of the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917, Vorovsky was named the Soviet government's diplomatic representative to Scandinavia, remaining based in Stockholm.[1] In Stockholm, Vorovsky was the point of contact between the new Bolshevik government and representatives of the government of Germany, being introduced by Alexander Parvus to members of the Social-Democratic Party of Germany including Philipp Scheidemann during November and December 1917.[6]

In December 1918, Sweden, responding to pressure on the part of the Allied powers who were intent upon imposing an unbreakable blockade, withdrew official recognition of Vorovsky as the representative of Soviet Russia.[7] This action on the part of the Swedish government forced Vorovsky's return to Russia the following month.[8] This action taken against Vorovsky followed the actions taken by Great Britain in expelling Maxim Litvinov in September 1918 and that of Germany in expelling Adolph Joffe in November of that same year.[9]

In March 1919, Vorovsky served as a member of the Soviet delegation to the Founding Congress of the Communist International.[1] He was named the representative of the Russian Communist Party to the Executive Committee of the Comintern.[1] He also served as one of the secretaries of the organization, along with Angelica Balabanova.[10] Grigorii Zinoviev was tapped as president of the organization.[10]

In July 1920, Vorovsky resumed work as a Soviet diplomat, participating in diplomatic negotiations with Poland.[1]

From 1921 to 1923, Vorovsky was the Soviet representative to Italy.[1] In that capacity he was involved in attempts at negotiation of a trade agreement between the two countries, with a preliminary pact signed in December 1921.[11] This success proved short-lived, however, as negotiations to extend the six-month treaty failed in May 1922.[11]

Vorovsky was a member of the Soviet delegation to the 1922 Genoa Conference, a group headed by Soviet Foreign Minister Georgii Chicherin.

Death and legacy

[edit]

Vorovsky's final diplomatic mission came in the spring of 1923, when he served as Soviet representative to the Lausanne conference of 1923.[1] Accompanied by two diplomatic attachés, Vorovsky arrived in Lausanne from Rome on April 27, hoping to force the conference's official participants to recognize Soviet interests in the Turkish Black Sea Straits.[12]

On May 9, Vorovsky dispatched his final report to Moscow, noting that three days earlier a group of right wing youths had appeared at his hotel and sought a meeting. Vorovsky wrote:

"I refused to receive them, and Comrade Ahrens, who went out to them to find out what it was all about, disposed of them at once, telling them that they should put such matters before their Government. Now they are going about the town declaring that they will compel us to leave Switzerland by force, and so on. "As to whether the police are taking any measures for our safety, we have no idea. At any rate, it is not apparent on the surface. It is only too evident that behind these hooligan boys there is some conscious directing hand — possibly foreign. The Swiss Government, well aware of what is going on — for the papers are full of it — must bear responsibility for our safety. The behaviour of the Swiss Government is a shameful violation of the guarantees given at the beginning of the conference, and any attack on us in this particularly well-organised country is only possible with the knowledge and permission of the authorities. On them is the responsibility."[13]

On the evening of 10 May 1923, Vorovsky was seated at a dining table in the restaurant of his hotel with his colleagues when the group was approached by an individual they did not know. The unknown figure, a Russian White émigré named Maurice Conradi, pulled a gun and shot Vorovsky to death, wounding his two companions, Ahrens and Divilkovsky, in the attack.[12] Conradi was defended by the advocate Théodore Aubert and later acquitted by the Swiss court in the epilogue of what would be known as the Conradi affair.

Vatslav Vorovsky was 51 years old at the time of his death. He is buried in Mass Grave No. 7 of the Kremlin Wall Necropolis in Red Square, Moscow.

Memory

[edit]

A number of settlements and streets in dozens of cities in the USSR were named after Vorovsky under Soviet rule. Among the significant renaming: Kiev Khreshchatyk, which was renamed into Vorovskogo Street between 1923 and 1937.

In Moscow, on 11 May 1924, in the courtyard of a former apartment building of the First Russian Insurance Company, a bronze monument of Vorovsky was erected under the project of sculptor Mikhail Kats. In connection with the installation of the monument and the demolition of the Vvedenskaya church located at the corner of Kuznetsky Most and Bolshaya Lubyanka, the vacated place was named Vorovsky Square.[14]

A poem by Vladimir Mayakovsky, titled Vorovsky, was dedicated to him in honor of his death.

The Palaces of Culture in the city of Konakovo, Tver region and in the city of Ramenskoye, Moscow region were named after Vatslav Vorovsky.[15]

In 1990, the Russian Coast Guard launched a Menzhinskiy-class (project 11351 - NATO Krivak III Class) ship named for Vorovskiy (Воровский 160).[16]

See also

[edit]- Alexander Griboyedov, Russian ambassador to Persia, assassinated in 1829

- Pyotr Voykov, Soviet ambassador to Poland, assassinated in 1927

- Andrei Karlov, Russian ambassador to Turkey, assassinated in 2016

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Branko Lazitch with Milorad M. Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern: New, Revised, and Expanded Edition. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986; pp. 498–499.

- ^ a b Shikman, A.P. "Воровский Вацлав Вацлавович 1871-1923 Биографический Указатель". Khronos. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ Schwarz, Soloman M. (1967). The Russian Revolution of 1905, The Workers' Movement and the Formation of Bolshevism and Menshevism. Chicago: Chicago U.P. pp. 258–59.

- ^ Futrell, Michael (1963). Northern Underground, Episodes of Russian Revolutionary Transport and Communications through Scandinavia and Finland 1863-1917. London: Faber and Faber. p. 156.

- ^ "Gosizdat". The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 3rd Edition (1970–1971). The Gale group. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ E.H. Carr, A History of Soviet Russia: The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1923: Volume 3. London: Macmillan, 1953; pg. 23.

- ^ Louis Fischer, The Soviets in World Affairs: A History of the Relations between the Soviet Union and the Rest of the World, 1917–1929. Second Edition. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1951; vol. 1, pg. 248.

- ^ Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 3, pg. 114, fn. 1.

- ^ Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 3, pp. 113–114.

- ^ a b Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 3, pg. 121.

- ^ a b Carole Fink, The Genoa Conference: European Diplomacy, 1921–1922. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1984; pg. 282.

- ^ a b Fischer, The Soviets in World Affairs, vol. 1, pg. 409.

- ^ "The Murder of Vorovsky," first published in Izvestiia, (Moscow) May 15, 1923; reprinted in Russian Information and Review (London), vol. 2, no. 35 (June 9, 1923), pg. 547.

- ^ The monument was created with the participation of the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs, the NKVD and the USSR mission abroad, as evidenced by the inscription on the back of the pedestal. The monument is made in a lively, mobile manner, testifying to the impressionistic predilections of the sculptor. The marble pedestal of the monument is made of stone sent by Italian workers

- ^ "ДК имени Воровского — Муниципальное Учреждение Культуры Дворец Культуры имени Воровского. город Раменское Московской области" (in Russian). Retrieved 2021-08-23.

- ^ "Coast guard patrol ships Project 11351". russianships.info. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

Works

[edit]- Советъ против партии (The Council Against the Party). Geneva: Bonch-Bruevich and Lenin Publishing House of Social-Democratic Party Literature, November 1904. —Reissued by Partizdat, 1933.

- Литературно-критические статьи (Literary-Critical Articles). Moscow: Gospolitizdat, 1948.

Further reading

[edit]- N. F. Piyashev, Воровский (Vorovsky). Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya, 1959.

- Marabello, Thomas Quinn (2023) "The Centennial of the Treaty of Lausanne: Turkey, Switzerland, the Great Powers and a Soviet Diplomat’s Assassination," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 59. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol59/iss3/4

External links

[edit] Media related to Vatslav Vorovsky at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vatslav Vorovsky at Wikimedia Commons

- 1871 births

- 1923 deaths

- Russian people of Polish descent

- People from the Russian Empire of Polish descent

- Soviet people of Polish descent

- Politicians from Moscow

- Old Bolsheviks

- Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members

- Russian communists

- Russian revolutionaries

- Russian expatriates in Switzerland

- Soviet expatriates in Switzerland

- People murdered in Switzerland

- Russian people murdered abroad

- Deaths by firearm in Switzerland

- Trade Representative of the Soviet Union

- Assassinated Soviet diplomats

- Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Italy

- Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Sweden

- Ambassadors of the Soviet Union to Denmark

- Soviet literary critics

- Russian Marxists

- Soviet people murdered abroad

- Assassinated ambassadors

- Assassinated Russian diplomats